When we peer down from the window of a plane, we can feel a type of awe that only comes from soaring hundreds or thousands of feet above our planet. Aerial perspectives give us brief opportunities to perceive the curvature of the Earth and the details of its topography, which are not visible from the ground or water.

Over the past decade technological advances in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), gimbals and camera/sensor miniaturization have made high-resolution imagery of our world’s dynamic land- and seascapes more accessible than ever, inspiring us aquatic types to work even harder toward preserving the environments we love.

Lately, I’ve been using small UAVs (also called drones or quadcopters) to take images of our watery world from the sky. Although aerial drone photography has been around for a while and there are scores of experts, I’m relatively new to it.

The learning curve has been uneven: While my initial forays were successful, I became overconfident in my skills and crashed my first UAV into the unforgiving redwoods near my home in California. I continued to be drawn to drone-produced images, but it took me a while to jump back in, in part due to lack of luggage space. With bulky dive gear and a heavy underwater camera rig, it can be challenging to find room for any other equipment. But with time, the size and weight of drones has dramatically diminished, and each new model has become even more easily transportable.

These advancements have enabled me to shoot aerial photographs more frequently, unquestionably reinvigorating my love of photography. Before I returned to quadcopters, I was in a photographic rut, using the same techniques to shoot the same subjects over and over again. The chance to photograph aquatic habitats and subjects from the air suddenly opened up a world fresh with potential.

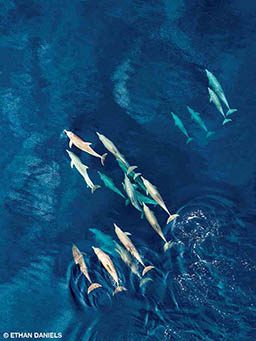

Diving and snorkeling show us our nearby surroundings in macro, but a little altitude offers new patterns and different details. Drones allow us to discern the proverbial “forest through the trees,” which may be why they have become such an indispensable tool for mapping and a number of scientific endeavors. They also afford artists new methods and inspirations.

Drone photography, despite its allure, can provide creative and mechanical challenges, but overcoming challenges to generate meaningful imagery is what we underwater photographers are all about, right? In my limited experience I have found that the same basic composition guidelines of underwater photography — the rule of thirds, diagonals, leading lines, negative space, etc. — also work well for aerial imaging. Like underwater photography, drone photography also allows the camera to be moved in three dimensions. The long range and nimbleness of small drones mean you can shoot from great distances and dramatically different elevations and angles. Consequently, UAVs have uses far beyond the artistic.

Researchers are now using UAVs to assist in identifying and counting plant and animal species, detecting disease in particular organisms, creating 3-D maps, monitoring oil spills and more. They are identifying areas and species being illegally fished, detecting phytoplankton blooms and saltwater intrusion, tracking marine mammals and endangered species and observing marine protected areas. Marine scientists are also currently using UAVs to examine coastal erosion, mangrove and seagrass communities, coral distribution and coral bleaching events. The list of potential uses is long.

Beyond their scientific and artistic capabilities, portable drones also help me find new dive sites and check wind, weather and even current conditions. I still examine satellite imagery to search for new sites that I may want to explore, but a drone lets me rapidly and more closely observe potential areas, with greater detail and without an internet connection. Through the drone’s eye, I’ve learned how to assess a site’s shallow reef health and bottom composition as well as determine approximate visibility and depth, all while savoring a cup of coffee.

Manufacturers are continually enhancing consumer drones with more capabilities in smaller and smaller packages; while these drones have tremendous scientific research potential, they also allow photographers to capture some of the most impressive images of the natural world — assuming the pilot knows how to fly them. Not everyone on Earth can visit the beautiful, biodiverse dive seascapes divers explore.

As Baba Dioum said, “In the end we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand; and we will understand only what we are taught.” These aerial images, which capture just a little of the ocean’s majesty, have the capacity to motivate people around the world to become involved in ocean conservation.

The human body has evolved to interact with the world around us through our capabilities and senses, but our vision can stretch only so far, and our bodies are landbound. Technological advancements allow us to fly higher and see farther. When we use drones to capture the planet from the sky, we can appreciate and conceivably understand more about Earth’s biodiversity than ever before.

| © Alert Diver — Q2 2018 |