Until last year, I had never seen an octopus while diving. That might not surprise most divers — after all, octopuses hole up in small dens, are quite excellent at camouflage and are most active at night. As divers go, however, I am more interested in spotting an octopus than most. I am a teuthologist: a biologist who studies octopuses, squids and their relatives (collectively known as cephalopods). Never seeing an octopus on a dive seemed like quite a blemish on my career, so I sought to remedy this problem and do some fantastic diving in the process.

We raised some octopuses from eggs in our lab at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, to study how their bodies acclimate to environmental changes. One of the many fascinating things about octopuses is that apparently the chapter in your high school biology textbook that describes how genes work does not fully apply to them.

Information in an animal’s DNA is supposed to be faithfully copied to the temporary middleman known as RNA before that RNA becomes a template for making a protein. Cephalopods, however, get really creative with their RNA. Most animals will make at most a few hundred edits in their RNA that tweak the composition of the resulting proteins. Cephalopods, however, make tens of thousands of these edits and therefore tweak thousands of their proteins to deviate from what is encoded in their genomes. How do they do this and why?

In our lab we found that water temperature influences many of these edits, but raising octopuses with carefully controlled water quality and a routine feeding schedule is not the real world. I wanted to confirm that these effects we saw in the lab are indeed present in wild populations.

Having never seen an octopus while diving, I knew I needed some help finding one to determine if they exhibited similar characteristics. The perfect person was Jenny Hofmeister, Ph.D., an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, who did her doctoral work on octopuses at Santa Catalina Island off Southern California. Not only would she know where to find them, but she could also help me secure a scientific collection permit for this research, which the National Science Foundation funded.

While we traveled to the dive site, I outlined my objectives, research and schedule, while Jenny and her protégé, Mohammad Sedarat, shared their octo-hunting secrets. You’re often not looking for the octopus itself but rather for tantalizing crannies that would make a great den. Octopuses search for somewhere that’s big enough to fit in comfortably but not so roomy that a predatory kelp rockfish can follow them in. A good, clear view unobstructed by algae is a must, and a back exit is a nice feature. Don’t expect to stumble upon an octopus roaming the reef. Think of yourself as a door-to-door salesperson checking every potential home you can find.

I knew that once I found an octopus it would be a challenge to get it out of its cozy den and into my inviting mesh bag. I also needed to find the same species we had raised in the lab: the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides). Fortunately, Jenny and Mohammad are among the best in the business at identification. The trick is distinguishing it from an extremely closely related species, Verill’s two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculatus). Their appearances, habitats and ecologies are as similar as their scientific names unless you find a female guarding her eggs. Online resources will tell you to look at the iridescent blue ring they display when stressed and consider if you found them in sandy or rocky environments, but these ID markers are not very reliable. I relied instead on my guides’ seasoned eyes and looked for the sign language “A” for Octopus bimaculatus or “O” for bimaculoides.

We found a den and identified the first animal. Injecting a small bit of white vinegar into the den behind the octopus might drive him out of the den, so I found a place to empty my 50 mL syringe, hoping not to push him further inside. I waited, trying to look as unsuspecting as possible. Either he’ll pump the vinegar out of his den with his jetting funnel, or he’ll try to make a break for it. But first he’ll make sure the coast is clear. I watched him creep progressively further out of the den, and then I made a quick grab to get him in the bag. I had many failures but enough successes to eventually head back to the boat with some animals to study.

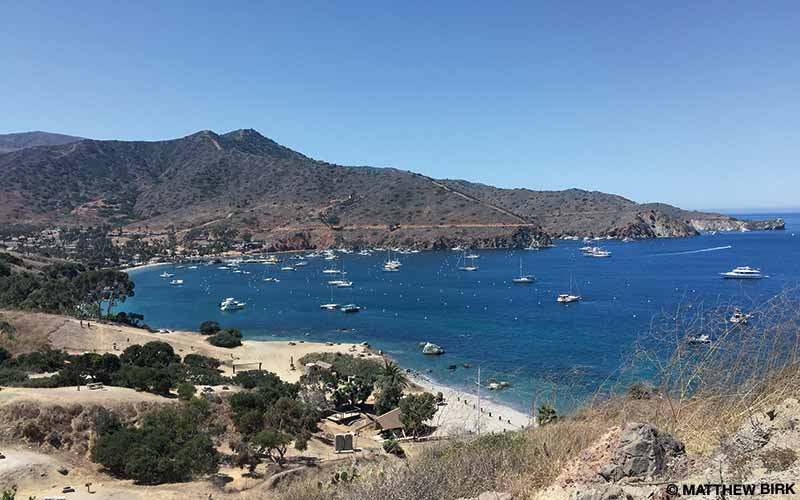

With the octopuses safely secured in a sealed bucket, we headed back to our base of operations at the University of Southern California Wrigley Marine Science Center to study the animals.

As the days of octo hunting passed among the bountiful underwater landscapes of the Channel Islands, the beauty and great joy of diving in this special part of the world struck me. My trip was scientifically productive, and I finally got to see plenty of octopuses while diving, but I needed to visit Catalina during the coldest time of year to validate that temperature-sensitive editing was occurring in wild populations.

The following February I returned to the island to collect more animals when the water had chilled by about 12°F from the previous summer. After that second trip, with my data-gathering concluded, I found myself wandering around the Los Angeles airport in early March 2020. I could hear a brief news story in the background about a new virus outbreak, and I wondered in passing whether I should wash my hands a bit more just in case.

Working on the leading edge of science can be quite exhilarating, but it can also be immensely frustrating. As it turns out, even the best experts in the world can sometimes be wrong. After all my DNA barcoding I discovered that all the octopuses we had caught were Octopus bimaculatus and not the bimaculoides species I was targeting. No one is to blame — we all knew how difficult it is to correctly identify them.

In many ways, that is the beauty of science. New data can show that we aren’t quite as good at understanding nature as we think. New findings can cause us to reassess what we think we know about the beautiful and immensely enigmatic underwater world that divers are privileged to explore. Now instead of merely validating lab-based studies, I am exploring how RNA editing evolves by examining both closely related species.

This is the essence of how science really works: Scientific endeavors are often the curviest path to an answer you weren’t expecting to a question you did not initially set out to ask. But from this messy track comes the discovery of the unknown and progress toward a better understanding of our world.

© Alert Diver — Q3/Q4 2021