The Indonesian underwater paradise known as the Coral Triangle is now widely regarded as the best of the best for marine-life diversity. Scores of liveaboards and land-based resorts provide comfortable and even upscale access to this incredible habitat. Divers can enjoy gourmet cuisine, elegant accommodations, skilled guides, nitrox and even Wi-Fi for posting digital images online to amaze friends back home with the region’s stunning beauty in real time. But it wasn’t always this way. Someone had to be there first. Someone had to explore and refine the adventure. Someone had to have the skill to communicate discovery in words and photos. For the Coral Triangle and the Bird’s Head Seascape, that pioneer was Burt Jones.

Jones’ long and circuitous road to the Coral Triangle began in central Texas, where his underwater inspiration arose in the 1960s in front of a black-and-white TV. He would watch enraptured as Mike Nelson dispatched the bad guys, usually with a knife to a double-hosed regulator, in Sea Hunt. Jones was an odd little boy; he’d sit in front of the television wearing a mask, fins and a pingpong-ball-topped snorkel. Sea Hunt had to sustain him for more than a decade — Jones didn’t even see the ocean until after he finished his studies at the University of Texas in Austin and headed south to Mexico to pursue a hippie lifestyle.

Beneath the jetty at Misool Eco Resort, a world-class dive has developed just a few years after this environmentally committed property created a marine sanctuary. The fish seem to know that they are in protected waters and have become accustomed to divers. Many species, such as the scads in this image, form dense concentrations, creating a myriad of photo ops. While I was occupied in shooting close-focus face shots, Maurine was photographing an equally impressive school of trevally. Her photographer’s sixth sense kicked in, and she looked up to see me posed in front of this anvil-shaped school. She got one shot before the school broke apart.

True to that ideal, he spent the first year doing mostly nothing. But in 1970 he decided to go back to college, this time in Cholula, Puebla, in central Mexico. There he earned his degree in anthropology before driving down to the Yucatan on a sabbatical.

The Yucatan of the early 1970s was not at all like the Yucatan of today. Puerto Morelos was the only real town there at the time. Playa Del Carmen had 200 residents — compared to about 200,000 now. Jones had heard that there was good scuba diving to be had on the island of Cozumel, provided you could catch the ferryboat to get there. At the time the ferry ran only twice a week, and he missed the first one, which left him with three days to camp on the beach and kill time until the next one came. Snorkeling off the beach, he found crystalline water and a pristine coral reef just 500 yards offshore — a discovery that set the hook for a life of underwater exploration. With lobster in every hole and conch so thick you’d stub your toe on them, Jones knew he wouldn’t go hungry. He didn’t bother catching the ferry when it departed again. Instead he opened the first dive shop on the coast, catering mainly to breath-hold spearfishers. Jones fondly recalls those years.

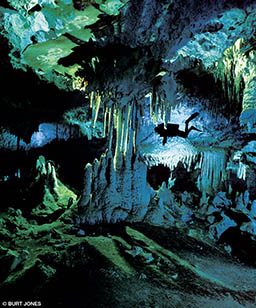

BURT JONES: I can’t say I was much of a photographer back then. In fact, I think I took about 12 rolls of film in 12 years. But I pretty quickly realized that spearfishing our local reefs was not a sustainable business plan, and I began to learn how to shoot underwater photos with a Nikonos. Diving the cenotes was what really transformed me and made photography an integral part of my life. I knew I needed to take that kind of diving seriously, so in 1984 I took a course and became a certified cave diver. It was the best course I’ve ever taken. I learned buoyancy control as a Zen experience, and I met Mike Madden, a true cave-diving expert who was then involved in exploring and mapping the Nohoch Nah Chich system.

By 1997 divers had explored more than 37 miles of that cave system, including 36 cenotes. But back in the mid-1980s we were camping in remote areas of the jungle, leapfrogging basecamps from sequential cenotes. That’s when I began to really take pictures, just because the cave system was so awesomely beautiful.

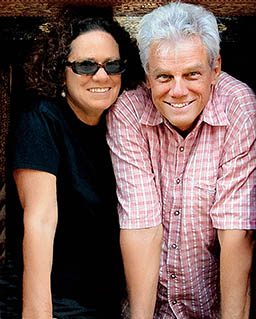

STEPHEN FRINK: I think many of us know you best as half of the photographer and writer team of Jones–Shimlock. I can picture you as the hippie living on the beach in Mexico, but when did Maurine Shimlock arrive in your tropical paradise?

BJ: In 1976 I was living in Puerto Morelos, and Maurine was finishing her Ph.D. in Latin American Studies at the University of Texas. We’d known each other casually in Austin and hit it off then, but it wasn’t until she traveled to Puerto Morelos that we reconnected. She knew a lot more about Mayan culture than I did, and she was a water baby to boot. So we embarked on a Garden of Eden existence together. Endlessly entertained by a place in time that will never again exist, we explored Mayan ruins and dived the barrier reef extensively, teaching ourselves more about underwater photography along the way. We moved onto a piece of property on the beach, as squatters really, but eventually we acquired ownership and built a bed-and-breakfast plus dive shop there. Combining the hospitality business with scuba and photography seemed like a good idea at the time.

SF: Well, clearly that didn’t stick, because we know you best for your work in the Asia-Pacific region. What took things in that direction?

BJ: A buddy had built a sailboat in Taipei and was headed out on a grand adventure. I was a big fan of the underwater photography of Douglas Faulkner, and much of his significant work was done in Palau. I told my buddy to give me a call if he ever made it there. Sure enough, one night I got a collect call: “I’m here in Palau. C’mon.” Maurine and I mulled it over the whole night, and by morning we’d convinced ourselves that this was the opportunity of our lives. So we made our way to Palau. Our baggage included our cameras, dive gear, an inflatable boat and four tanks. We saw diving that would change our lives forever, and I mean that in the best possible way.

In the early 1980s we were diving Palau, and we made our way to Papua New Guinea, too. We saw things underwater that very few had seen. In 1988 we got jobs as cruise directors on the first liveaboard operating in the Solomon Islands, the Bilikiki. We worked with owner Rick Belmare to refit a mostly derelict fishing boat moored in a port in the Florida Islands. This boat had table corals that were 6 feet across growing on its hull, but we helped transform it into the world-class liveaboard it eventually became. We were proud to have been there for the early years; we set up the E-6 film processing capability and worked with Chris Newbert and other photographers to create itineraries particularly well suited to underwater photography groups. We did that for two years and then made our way back to Austin with an idea to write articles, sell photos and take people on scuba safaris. That’s what our company, Secret Sea Visions, was set up to do.

SF: I remember your stunning debut coffee-table book, Secret Sea. That was beautifully photographed and insightfully written. How did that come about?

BJ: I mostly shot fish and macro back then, and Maurine concentrated on the wide-angle photos. Together we had accumulated quite a portfolio of underwater transparencies. Newbert introduced us to the women who were publishing Ocean Realm, a high-quality quarterly dive magazine. They published our work first in 1990 and introduced our photography to our peers and the broader dive industry. They also published Secret Sea in 1996, which won the Ben Franklin Award from the Independent Book Publishers Association for the best book printed in 1996. This was a time in our lives in which one thing often led to another, but if I were going to point to the one synergy of that era that most influenced our lives, it would be connecting with Kalman Muller.

Visitors to Horseshoe Bay off southern Rinca Island in Komodo National Park will be greeted by a number of dragons. This habituated behavior, instigated by liveaboards that began feeding kitchen scraps to the dragons, is not normal, but it does provide the unique opportunity to get up close and personal with the dragons. Komodo dragons are good swimmers and will swim across a mile or two of open water if the next island has a good food source. They can be aggressive, and extreme caution is always advised when approaching them on land or from the water. What you don’t see in this image is one of our tender boat drivers standing behind us with the hefty forked stick he used to fend off the world’s largest lizard.

Kal had lived and traveled extensively in Mexico, so we had that in common when we met on the way to Sipadan Island in Malaysia in late 1989. He was working on the first dive guide for Indonesia, Diving Indonesia, and we hit it off immediately. His second edition of the dive guide was in the works in 1993 when he invited me to go with him to Komodo on an exploratory expedition via liveaboard.

Also on that trip were two of the most influential fish-identification experts in the world, photographer Roger Steene and Gerry Allen, Ph.D., an esteemed authority on the classification and ecology of coral reef fishes of the Indo-Pacific region. This was heady company indeed and a grand adventure. It was a rough and rugged trip, not like the luxury liveaboard tours of today. But we saw amazing things.

We pulled into Horseshoe Bay and watched a Komodo dragon climbing to a big rock maybe 150 feet above the beach. We followed it up there hoping for a photo-op and found it eating a smaller dragon. From that lofty perch we looked down and saw a bit of reef we didn’t know was there. We resolved to dive it the next day, and Gerry was blown away by it. There were tropical fish and temperate fish all swarming in one place because of cold-water upwelling and mixing currents. It was such an inspiring dive, and when we reflected on the sight of one Komodo dragon eating another, the site named itself. Cannibal Rock is now one of the most famous dives in Indonesia, deservedly so.

After we saw our first pygmy seahorse during a 1996 dive trip to Komodo, we visited Larry Smith, who had just moved to Sulawesi’s Lembeh Strait. We showed the host sea fan to Larry and his dive guides, who then began finding these tiny seahorses everywhere. Scientists flocked to Lembeh, and new species and new host sea fans were discovered. Over the years we have photographed many individuals, but now we seldom invade the seahorses’ territory unless the image has powerful potential. In Raja Ampat’s Aljui Bay we found this Denise’s pygmy seahorse peering out from behind its host sea fan. The negative space provides a sense of scale, and the fish’s pose evokes humor; it’s one of our pygmy favorites.

SF: Being in Raja Ampat and Komodo at that time you must have come to know Larry Smith, one of the most famous dive guides to ever work the region.

BJ: Yes, of course. I first met Larry in 1995 when he was working in the Banda Sea, and we ended up on a boat together. He was telling me about a dive site at Ambon Island that had really weird little things. He described a fish that sounded like something a cat coughed up. I wondered if it might be a Rhinopias, and I was beyond excited to possibly see such a rare (at the time) fish. The site was near Laha in Ambon Bay, and we did seven dives the first day and nine the next. To our astonishment, we saw Rhinopias and nine different frogfish on the pier pilings, Coleman shrimp on a fire urchin, and flamboyant cuttlefish. The list of personal discoveries just went on and on — it was an absolute critter mecca. I think muck diving was born that day. By 1996 Larry had moved to Lembeh Strait to develop more of the same, and as far as diving in Indonesia goes, the rest is history.

Manta Alley off southern Komodo Island is known as a one-stop service center for mantas. It’s where they come to feed and be cleaned by a variety of smaller fish. When a strong current flows through a small opening between an islet and a submerged rock, manta food or plankton becomes especially concentrated, and mantas show up to feed in greater numbers. On the day this image was shot, the current was screaming, and it was all I could do to maintain a position hunkered down near the substrate. It was worth every sore muscle because the manta action was superb.

SF: I know you are now closely associated with Conservation International. What are you collectively hoping to accomplish in your special part of Indonesia, the Bird’s Head Seascape?

In early World War II, the Japanese sustained heavy losses in the Solomon Islands’ Savo Sound, which became known as Iron Bottom Sound. Most of the wrecks there are too deep to dive safely on scuba, but there are hundreds of easily dived wrecks throughout the western Solomons. By isolating a single feature on this sunken artifact and adding a diver, our image tells the story of how wrecks have become a tourist attraction and are finally having a positive influence on the country instead of a destructive one.

BJ: Our stated goal is to incorporate tourism into a conservation plan, and our chief collaborator is Mark Erdmann, Ph.D., now vice president of Conservation International’s Asia-Pacific Marine Programs. Larry Smith, prior to his death in 2006, joined Gerry Allen, Mark Erdmann and I for countless hours underwater together throughout Raja Ampat. Later we expanded our explorations to include Triton Bay and Cenderawasih Bay, which together with Raja Ampat became known as the Bird’s Head Seascape (BHS).

In 2008 Maurine and I were hired as sustainable marine tourism consultants, tasked with promoting and publicizing the region. This was especially meaningful, as it was the first time a conservation organization had incorporated tourism into its plan. Conservation International supported and encouraged our first guidebook, Diving Indonesia’s Raja Ampat, in 2009 as well as our 2011 book, Diving Indonesia’s Bird’s Head Seascape. Our website, BirdsHeadSeascape.com, was designed to be a repository for the ongoing scientific work in the BHS, a venue for photographers and writers, a way of informing the public about environmental news and events in eastern Indonesia and as the go-to site for information for travelers visiting the BHS.

SF: From the point of view of someone who has been fortunate to see the most pristine reefs on earth before just about anyone else, do you have any insights you can share with us in closing?

BJ: Given the time we’ve spent in so many beautiful places on the planet, and given the degree to which we’ve seen change creep into these ecosystems during our few brief decades of exploration, we know our continuing efforts need to stay rooted in marine conservation. We have to communicate how weird and wonderful these creatures are and how fragile their balance of life is.

I know these have been very special times. It occurs to me that our job descriptions, yours and mine, didn’t exist for our parents. The technology of scuba diving was barely there for them as young adults, and dive travel certainly was not evolved back then. They couldn’t have done what we did for a living. And I fear it won’t exist for our grandchildren unless we can seriously curb overfishing, ocean acidification and the rampant effects of climate change that are profoundly affecting our coral reefs and pelagic marine life. We’ve lived the sweet spot. To see what we’ve seen, to do what we’ve done — we were some of the lucky few. It’s a privilege for which I’m grateful every day of my life.

On any given day, a good muck site’s substrate will boil with action. I was framing a frogfish when a rapid peripheral movement caught my attention. I saw this lizardfish with a captured triggerfish hanging out of its mouth. Even though the triggerfish appeared to be lunch, its erect dorsal and ventral spines prevented the lizardfish from swallowing it. I was able to shoot just a single frame before the triggerfish escaped. This is one of those images that define the importance of becoming familiar with your equipment and settings to the point where you can just grab a great shot without taking your eye off the subject.

| © Alert Diver — Q2 2017 |