I first “discovered” Jerry Greenberg when I was a dive bum living in Kona, Hawaii. I was (barely) making a living photographing drunken tourists at hotel luaus by night and practicing underwater photography during the days. Getting good color on my subjects seemed to be the big issue, especially compared to all the vibrant underwater scenes collected in postcard racks all around the island, all marked © Jerry Greenberg. I bought a copy of his seminal text Underwater Photography Simplified, and began to gain an appreciation of the physics at work in photographing in the sea.

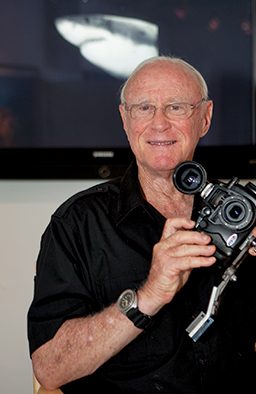

An Interview with Jerry Greenberg

I finally met Jerry in 1978. By then I’d opened a small underwater photo business in Key Largo, Fla., renting cameras and processing E-6 slide film. Jerry dived Key Largo quite often and eventually trusted me to process a few rolls of his Ektachrome. You can bet on the days I processed Jerry’s film I made sure the replenishment, temperature and time in the chemicals were spot-on. I did not want to be the guy who screwed up Jerry Greenberg’s film! Over time, Jerry became a close friend and mentor and I knew we’d moved beyond a “darkroom” relationship he brought Rick Frehsee, another prominent South Florida shooter, to Key Largo to meet me for dinner. The agenda for that evening was something like, “Hey kid. There’s a chance you might make it in this underwater photography thing, and if you do, there are some things you need to know about business and copyright.” For 90 minutes, Jerry and Rick gave me a crash course in protecting my rights and how to handle myself with publishers. He gave me two other take-aways from that dinner that I’ve never forgotten (maybe because he’s reminded me so many times since):

- Never believe your own press clippings.

- Never judge the work of another photographer by what you see printed in

Now, on the occasion of Jerry’s 82nd birthday, we are proud to honor the art and innovation in underwater photography that has defined his career.

SF: You’ve been taking underwater photos for more than six decades now. You must have an absolutely massive archive of photographs.

JG: I do have serious quantity, but like any serious photographer, I have very few iconic photographs. Whether it is Henri Cartier-Bresson or Alfred Eisenstadt or David Douglas Duncan, there are a few images that deserve to be famous, and the rest should “rest in peace.” Frankly, as I look to the future, maybe 10 years down the line, I think there may be more value in my wife’s artwork. My photos will inevitably be usurped by new, up-and-coming photographers, but I predict her artwork will long endure.

SF: I love hearing your stories about how you started diving in Key Largo and your earliest adventures with underwater photography. You always admonish me not to use the “p” word in describing you (as in “pioneer”) so I won’t, but clearly there was no roadmap for underwater photographers when you started out. How did you carve out your direction?

JG: My parents bought a winter home in Miami Beach back in 1937. Winters were seriously cold in Chicago, and we loved South Florida. I went to grammar school here in those early years and spent afternoons and weekends swimming — snorkels hadn’t been invented yet — around the piers and spearing small sergeant majors with a wire hanger spear and a Hawaiian sling. I saw some pretty amazing sights, so I took a glassbottom bucket and shot with that as my window to the sea using a Brownie camera. By 1946 I’d moved up to a homemade housing for a Baby Brownie Special, and with that I could work in shallow water. I never trusted it to go deep, but at least I could actually submerge it.

From 1948 to 1952 I went to college on the GI Bill and learned how to use a Leica camera and, what was at the time a wonder of wide-angle, the Hektor 28mm lens. That was my ideal camera, but I didn’t know of any way to take it underwater. Instead, I had a case made for a Luftwaffe Robot camera (essentially a German gunnery camera from World War II), but it leaked constantly. My real equipment epiphany came when I read an article in a 1951 issue of Leica Manual by Peter Stackpole describing a cylindrical brass housing, complete with large knurled caps to seal either end of the housing, allowing the camera to slide into the housing along a special track. The camera and housing were heavy, about 9 pounds, and even then underwater photography was an expensive hobby. I bought mine from the same guy who designed Peter Stackpole’s, and it cost me $150. That might not seem like much, but remember that in 1951 you could buy a brand new Chevy Bel Air for $1,900!

By 1952 I had taken one of my most famous pictures with it, a black-and-white of a massive school of porkfish from Molasses Reef; and I had a big feature with my work published in Leica magazine.

(Editor’s Note – One of the earliest popular housings was the Rolleimarin, designed by German engineer Richard Weiss for Franke & Heidecke, under the direction of Hans Hass. This was not patented in Germany until July 1953, making this early brass housing for Leica one of the very first commercial housings.)

SF: What was it like to dive the Florida Keys back in the early 1950s?

JG: I don’t know that the visibility was all that much different, really. There were no doubt more really good days, and when it was good, the clear water probably went closer to shore. But we still have days of better than 100-foot viz in Key Largo, and I doubt the best days in the 1950s were any better than that.

The reefs were certainly more lush on top back then, particularly with Acropora palmata (elkhorn coral). Some reefs were better than others. French Reef looked like a bomb went off, even back then, but Key Largo Dry Rocks was stunningly beautiful. They didn’t put the Christ of the Abyss statue at Dry Rocks accidentally. That was the most beautiful reef in all the Upper Keys in 1960. Also, the grouper populations were unreal. We called the ledges “grouper hotels,” and the fish were stacked pec-to-pec under the overhangs.

But, nothing lives forever. The sequoias might have been there since the birth of Christ, but coral reefs come and go. I see the corals coming back out at Horseshoe Reef with a vengeance. And now you have guys like Ken Nedimyer actually growing staghorn in a nursery and planting it out on the reef. He’s the Johnny Appleseed of Acropora. That’s very exciting stuff!

But, yes, of course it was better in the old days. There were certainly lots more grouper and jewfish, and the shallow branching corals at places like Carysfort were so exquisite it would bring a tear to the eye. We’ll never see that again.

SF: One of the most memorable underwater photo spreads I’ve ever seen happened to be by you, in a 1962 edition of National Geographic. As a kid living in the Midwest, I was in awe of your two-part series, “Key Largo, America’s First Underwater Park” and “Florida’s Coral City Beneath the Sea.” That had to be a very special time in your life.

JG: I was very proud of my work with National Geographic. Bill Garrett was a terrific editor, and in the 1960s and 1970s I had more photos published in National Geographic than any other freelance contributor. I wrote extensively about that assignment in my 1971 book Manfish with a Camera, and it was the results from that assignment that to a great extent fueled my early stock photography business. I did another major story for them on sharks in 1968 and then an underwater photo essay featuring my wife and three kids in St. Croix in 1971 entitled “Buck Island, Underwater Jewel.” Of course, my dear friend David Doubilet holds the record for underwater covers and articles in National Geographic, but I had a nice run with them for quite a while.

The last major piece I did for National Geographic was in the July 1990 issue. Done in collaboration with Fred Ward, “The Coral Reefs of Florida Are Imperiled” may be one of my most significant works, not because I was documenting the degradation of the coral reef with “then and now” images, but because it raised awareness. High-ranking politicians at a national level saw that story, and I’m told it was no coincidence that the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary was authorized that same year. That may be the greatest contribution I ever made to the reefs I love so dearly — their ultimate protection.

SF: I remember ads in old Skin Diver magazines for Seahawk camera housings. At some point you were a housing manufacturer as well.

JG: In the very early days, before I was a full-time photographer, I worked for my dad, who owned a textile mill in Arkansas. I was working for him in Chicago and at the mill; very soon I realized this was not the career for me. Then I saw a short film by Jacques Cousteau. I was so inspired I told my dad I had to try this underwater photography thing! He bought me a station wagon to hold my camera gear and Leica enlarger, and off I went, back to Miami Beach, to join a guy who’d invited me to build underwater camera housings with him. The camera we chose was a Baby Brownie, and the guy was Jordan Klein, who went on to become a famous cinematographer, working on the early James Bond films and the Flipper TV show.

We worked together for about a year and a half making Mako housings. Then I went off on my own to make Seahawk housings, named after my favorite Errol Flynn movie. My biggest seller was the Seahawk for the Argus C3; a $59.95 cast aluminum housing that was good to 150 feet. I eventually made housings for the Argus C4 and C-44, Leica, and Contax as well as a bulb flash unit and a housing for a popular “potato-masher” style strobe (Heiland Strobonar 64).

The housing business was good to me until the day I tried a Nikonos I camera with the 28mm lens. That lens was so sharp, and the convenience of the amphibious camera was so good, the handwriting was on the wall. I quit making housings then.

SF: I remember a quote Rick Frehsee shared about you. He said, “Jerry Greenberg has three of every underwater camera ever made, but two don’t work.” From that I deduce you’ve had a diverse collection of gear over the years.

JG: Yes, I’ve had plenty of gear over the years, and mostly they do work! But there were always things I wanted to do with underwater photos, and the existing gear wasn’t there to support me. When the Nikon F cameras introduced their Action Finder, that became the right camera to house, and I created a housing with a 250-exposure back. I put a Widelux camera in my own housing using a compass dome for my port. I shot a lot of panoramas with that rig! I had what I call my KraptoFlash — you’d have to

know about Buck Rogers to appreciate that name — with three small flashes that nicely lit the entire reef. I continued to tweak and invent products to fit my needs, but eventually I could buy quality gear. Over the years I’ve had Rolleimarins, Giddings-Nikomar, Calypsos, every iteration of the Nikonos, the Aquatica for the Nikon F3, Tussey housings for my Nikon 8008, Oceanic Hydro 35 housings from Bob Hollis and the Aqua Vision dome that adapted virtually every Nikon wide-angle to my Nikonos.

Actually, just before the digital revolution hit I started to regress a little. I really loved my Sea & Sea MotorMarine II. It had variable synch speeds and was very easy to use. I could add wide-angle and macro accessories with an external bayonet. And when the MotorMarine III came out I thought I’d found my ultimate camera! It had an ultra-sharp 20mm lens, and you could still add accessories to go wider (I loved the 15mm add-on lens) or shoot macro. Film was already on its way out when it was introduced, but I still think it was terrific.

SF: Have you made the migration to digital yet?

JG: Yes, albeit grudgingly. I think these digital cameras have too damn many buttons! I have a Sea & Sea 1G that I really like now that I had the housing modified to have a clear Lucite back over the camera’s LCD instead of the smoke-gray one that it used to have. I also have a Canon G9 in a Canon housing and another one in an Ikelite housing, and a Canon G10 in a Patima housing. My newest acquisition is a Sea & Sea DX-2G. As you can see, I’m not keen to use a big digital SLR. I like the size and ergonomics of the smaller cameras, although the digital lag is an issue for photographing some subjects. I use Ikelite strobes for just about everything and have for many years. They are a quality company with excellent service and reliable products. But truthfully, I can’t cope with the devil’s tool (my name for computers). My wife, Idaz, uses them, and my son, Michael, is a genius with them. He does these virtual tours of coral reefs that you can click to expand for a closer view. Amazing stuff, which I can appreciate, but the new computers and most of the cameras still have way too many buttons for me!

SF: Where do you see the future in underwater imaging?

JG: This is an exciting time to be an underwater photographer. There are some really great photos being shown on wetpixel.com, the stuff you are doing, and the things I’m seeing featured in the new Alert Diver. People are traveling farther and spending more time in the water, capturing strange and beautiful behaviors. When I began doing underwater photography I had to invent gear and techniques. It’s not like that anymore. But don’t use the “p” word on me. I’m not the pioneer. There were plenty of great photographers who went before me: William Longley, J.E. Williamson, Peter Stackpole, Luis Marden and Dimitri Rebikoff, among many others. We all stand on the shoulders of giants.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2010