From the size of Yan’s eyes, it’s obvious that he is onto something. As soon as he’s sure we’ve seen him, he spins and swims like a missile back in the direction he came, with Anna and me trailing behind. When he settles on the sand next to a low-profile mound of Galaxea coral the size of a trashcan lid, we immediately realize that he’s found a pughead pipefish — a toothpick-sized coral symbiont that we’ve been hunting across Indonesia and the Philippines for the past two years.

With an outstretched hand, Yan slowly fans the colony. The gentle current causes the polyps to retract just enough to reveal a mated pair of pugheads weaving their way through the tentacles like snakes through grass. Red-eyed, white-faced and bedecked with speckles, the little chocolate-brown wonders are more exquisite than we imagined.

At that time we believed that the species was rare, but it turns out they’re far more common than we knew. Before Yan’s discovery, we didn’t have the right search image to find them. Search image is a biological term describing how predators use their experience to form mental images for detecting cryptic prey. Naturalists have usurped the expression to explain why it becomes much easier to find a species once you have observed it in its natural habitat. For example, after the other guides on our liveaboard saw where the pughead pipefish live and became aware of their size, appearance and behavior, they quickly began showing off pugheads to their guests.

Our hunt for the pughead pipefish not only illustrates the power of search images and the value of local knowledge but also reaffirms how difficult it is to find something you’ve never accurately imagined. Fortunately, the sea is full of unimaginable things still awaiting discovery, and most, like the pugheads, are small.

Amphipods

About a year ago, I began hearing stories about little buglike crustaceans known as amphipods that make their homes inside tunicates. Since then I had been squinting inside the openings of tunicates without a bit of luck until we took a trip to a seaside resort town of Anilao in the Philippines. The local reefs support a thriving population of bluebell tunicates. Inspired by the bluebells’ delicate beauty, I once again took up my quest for amphipods but with no luck.

Lazing around the boat between dives, I casually confess my failings as an amphipod hunter. Our guide looks up from his cup of tea and makes a most unexpected offer. “They live so deep inside you rarely see them by looking into the openings,” he said. “Loan me a flashlight, and I’ll find you one on the next dive.”

The boat drops us near a shallow ridgeline festooned with bluebells. Instead of shining his light inside the openings, the guide aims the beam at the opposite side of the translucent tissue. Minutes later he points to a small silhouette fidgeting inside near the base. Apparently disturbed by the light, the amphipod scrambles up the side, leaps like an acrobat over the rim and lands inside a neighboring tunicate, where it sits on its haunches staring at me indignantly.

Clown Crabs

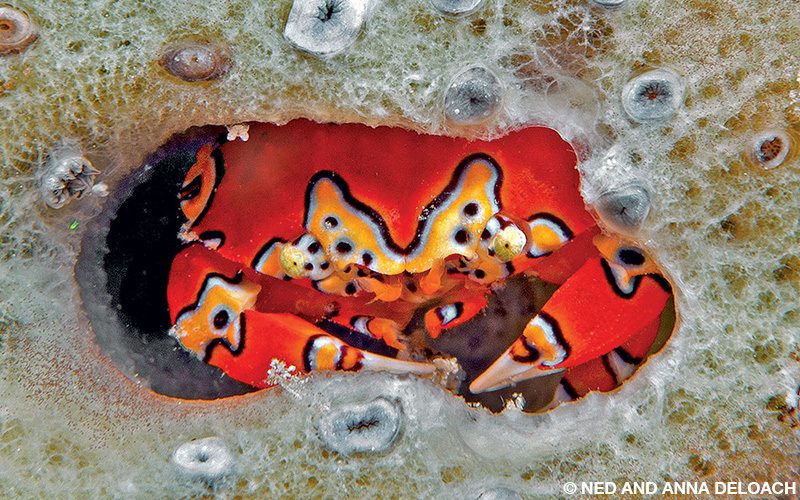

Although not much bigger than a button, clown crabs are one of the most prized crustaceans in the Caribbean. Their stardom stems from eye-catching color schemes exhibiting the flamboyant exuberance of street art. The patterns are never quite the same on any two crabs, making their attire even more appealing.

Unfortunately, clown crabs are not easy to find. During decades of searching, Anna and I have found less than a dozen, always at night when they creep out of hiding to feed. We are delighted when a guide on the western Caribbean island of Utila explains how to find the crabs during the day. Sure enough, his tips work to perfection. On our two morning dives we find four clown crabs tucked away right where he said they would be: inside carapace-sized cavities excavated in the sides of rope sponges. He had also suggested that we look for branches infested with zoanthid polyps.

The crabs hollow out the sponges as safe havens, where they hunker down during the dangerous daylight hours when predators prowl. The guide’s clue about the zoanthid polyps had us baffled, however, until we later learned that they are the favorite food of clown crabs.

Sea Slugs

Siphopteron hunting begs the question of just how small is too small. Aside from the challenge of spotting these peppercorn-sized relatives of nudibranchs, the tiny, shelled mollusks spend far more time burrowing beneath the sand than gliding across the surface. But if you ever have the fortune of encountering one of these little beauties, I guarantee you will be on the lookout for others — they’re that wonderful.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2020