It’s the day you hoped would never arrive: the last day of vacation. With your flight home less than 24 hours away, you’re done diving for this trip. Wanting to make the most of your final day, you and several other members of your dive group decide to follow a trail you noticed earlier in the week. Twenty minutes later, a playground of tidal boulders appears before you. Your group rises to the occasion and starts exploring like a bunch of kids. Ever accident prone, your buddy’s excitement outpaces his spatial awareness and his feet slip from underneath him on the wet rocks. He is caught off balance and falls, landing on his back on a boulder far below. As he tumbles off the boulder down onto the sand, you carefully make your way over to help.

Hold On

When dealing with a suspected spine injury, the first step a rescuer should take following a scene assessment is the immobilization of the injured person’s head. Immediate immobilization is important to minimize the risk of injury (or additional injury) to the spine. Firmly grasp the head and hold it still in the position in which it is found. This is such a quick and easy step, it can be done even before assessing airway, breathing and circulation (the ABCs). It is good practice to take this step in all first aid situations, even those in which no significant mechanism of injury is apparent.

Once the ABCs are established, the rescuer should try to determine exactly what happened to the injured person. If there are no witnesses, the rescuer should ask the person directly. Any indication of force sufficient to cause injury to the spine (e.g., sudden deceleration, a fall from a height or direct trauma to the spine) should prompt the rescuer to continue stabilizing the person’s spine by holding his head. If the person reports an accident that could not have caused injury to the spine (“I cut my finger while using this knife” or “my stomach started hurting, so I sat down right here”), it is appropriate to let go of the head. When in doubt, maintain immobilization.

Note that the rescuer’s initial decision about whether to hold on to or let go of the head is based on the mechanism of injury (how the injury occurred). At this point, the decision does not take into account symptoms or a lack thereof. The rescuer has not yet gathered enough information about the person’s status to determine whether or not a spine injury has actually occurred; the relevant issue is whether the sustained injury could have damaged the spine.

Spine Injuries

The spine is a column of 33 bones (the vertebrae) that provides structure and protection for the spinal cord, an important bundle of nerves. An injury to the vertebrae does not necessarily indicate damage to the cord, but any injury to the spine must be treated with extreme caution as fractured vertebrae put the spinal cord at risk. Symptoms of a fractured vertebra include pain, tenderness and bruising at the injury site. Crepitus, the sound of bone ends rubbing together, might also be present. If the cord has been injured, additional symptoms may be observed, including diminished sensation in the hands or feet, weakness, paralysis, incontinence and signs and symptoms of shock (inadequate circulation of blood).

As a general rule, moving people who may have spine injuries requires specialized training and should not be attempted by untrained rescuers. Doing so without proper technique risks turning a vertebral fracture into a cord injury. If it has been determined that the mechanism of injury could have caused damage to the spine, the person should be stabilized in place.

C-Collars

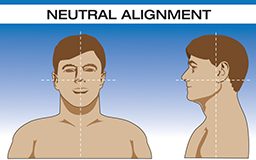

In addition to manually immobilizing the head, rescuers can employ various adjuncts to improve stabilization. One such adjunct is a cervical collar, or C-collar. C-collars are utilized by Emergency Medical Service (EMS) professionals everywhere, but they are generally not practical for travelers’ first aid kits. C-collars are, however, easy to improvise. Before an improvised C-collar can be utilized, the person’s head should be in neutral alignment. Once the ABCs have been addressed, it is appropriate to turn the person’s head slowly and gently into neutral alignment. This is an exception to the recommendation not to move people who may have spine injuries. Although moving the whole person is not advised, careful and deliberate movement of the head is appropriate if done correctly. The head should only ever be moved into neutral alignment, never out of it. Stop immediately if this movement toward neutral alignment causes the person any pain or if there is mechanical resistance. Aligning the head not only allows a C-collar to be used, it also improves the airway and increases comfort, which is important since immobilization may be required for some time.

If an actual C-collar is not available, one method of improvisation is to roll up a sweatshirt with the sleeves out to the sides. Place the body of the shirt over the person’s neck and carefully pull the sleeves through underneath. Check with the person to ensure it does not impair breathing and is not uncomfortably tight. It is important to note that employing a C-collar does not allow a rescuer to let go of the person’s head; it is simply an added measure of safety and a reminder to the person not to move his or her head.

Evacuation

When a rescuer has committed to maintaining spinal immobilization, it is necessary either to call for help or send other members of the group to go and get it. If the rescuer is alone and making a call is impossible, the remaining options are not particularly good. The rescuer must either wait with the person or leave the injured alone to find help. Waiting is a reasonable course of action if discovery is likely, or if friends or family members are likely to initiate a rescue within a reasonable period of time. What constitutes a reasonable period of time depends on the injured person’s condition, the temperature and other environmental factors, as well as the resources at hand.

Leaving an injured person alone is a last resort. One major problem with this course of action is that it may necessitate placing a person on his or her side to ensure the airway remains open. Although this violates the recommendation to keep the injured immobile, a person with a spine injury may have a limited capacity to maintain his or her own airway. Since the airway is the highest priority in first aid care (when in doubt, refer back to the ABCs), it takes precedence, despite the risk of an exacerbated spinal injury.

Even caregivers trained in backcountry rescue generally do not transport persons with potential spine injuries without using specialized equipment. Trained rescuers use a variety of advanced techniques to put those injured into positions that facilitate care or safely move them onto a backboard. But transporting a person over any distance warrants the use of equipment made specifically for that purpose. Consider this when deciding whether to move a person using the resources that are available on-scene or whether to send for help: As with any rule, there are exceptions — situations where leaving a person in place may be more risky than moving them. A person immersed in cold water, for example, is at risk for hypothermia or drowning. Similar judgment calls will arise in cases where persons are in open areas with imminent electrical storms, on slopes with unstable snowpack, or in dry creek beds with heavy rain coming.

Wilderness medicine courses offer training in techniques for safely lifting, moving and transporting people who may have spinal injuries. They can also teach how to decide when to rule out a spinal injury and discontinue manual immobilization. Knowing when and how to make that decision can make care and rescue logistics dramatically easier, but it involves an extensive physical exam and evaluation of cognitive, motor and sensory functions. A thorough description of the decision protocol is beyond the scope of this article, so whenever a sufficient mechanism is present, it is best to maintain spinal immobilization. While problems with airway, breathing and circulation represent the most imminent threats to a person’s life, attention to potential spine injuries may be the next most important component of care in a remote setting. Taking proper precautions when a spine injury may be present can have a substantial impact upon a person’s future quality of life.

Get Trained

As more people spend time traveling, exploring and diving in remote environments, several organizations have emerged to provide training in wilderness medicine. Training programs range from weekend-long Wilderness First Aid courses to month-long Wilderness EMT courses. Prior experience is generally not required. For more information contact the Wilderness Medicine Institute at www.nols.edu/wmi.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2011