It’s night, and I’m 65 feet beneath the surface, hanging tight to a taunt line attached to a skiff that’s being sucked toward open sea by a stiff current flowing out of Ambon’s harbor. I’m exactly where I want to be: on the hunt for oceanic voyagers that rise from the depths to feed after sunset — most are seldom-seen bits of gossamer that look like nothing else on Earth. And I’m having the time of my life.

My guide, Semuel, grips the rope to my right. He and his light are home base in a game of open-ocean night tag. The game is going well. In the 20 minutes we’ve been down, I’ve already encountered at least a dozen eye-popping animals. Although small, delicate and ornate, these otherworldly creatures are far from passive drifters — most can swim like the dickens. My mission is to chase them down and photograph them. It’s easy to get caught up in the effort, but no matter how spectacular the animal, at some point — for safety and sanity’s sake — I have to break away and reestablish contact with Semuel.

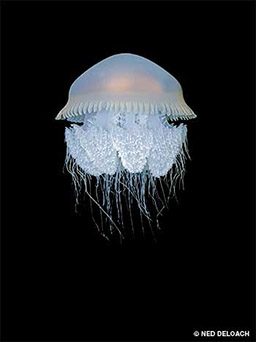

For a long few seconds afterward I don’t have a clue where he might be — up, down, to my right or to my left. Spinning, I spot his light and head for it in a sprint. No sooner do I make it back than a jellyfish the size of a soccer ball appears out of nowhere, moving fast and heading in our direction. It’s a glorious thing that glows like a jack-o-lantern in my beam.

I release the line and move fast to head it off. What a classic animal — a worthy representative of one of Earth’s most ancient life forms, a gelatinous symphony of radial symmetry with a half-billion-year track record of survival, including making it through five mass extinctions. At first a single fish and then others awakened by my light peer out from the frilly skirt in bewilderment. Inside the lace, a cluster of the tiny hitchhikers dart around in a huff. Most are juvenile jacks, orphans from the sea taking refuge from predators. Out of nowhere an inner voice reminds me that if I want to continue playing the game I have to play it right. I put on the brakes and watch the jellyfish sail out of sight.

A later jellyfish encounter takes place at midday in the middle of Lembeh Strait in Indonesia. It begins with a shadow passing beneath the bow as our water taxi/dive boat nears the mooring. Through the chop we can just make out the broken outline of a large jellyfish heading toward the center of the strait. I begin putting on my gear. Our Indonesian guide, Ben, shouts for Abang to cut the boat hard right. Anna scrambles onto the top of the flat cabin to track the animal’s course. She begins barking advice, but it’s not what I want to hear: “Don’t get in; it’s heading for the boat channel.”

Ben looks up and down the strait and makes an executive decision; he shouts over the engine for Abang to pull alongside the jellyfish and cut the engine so I can tumble in. He lowers my camera to me and then springs up onto the roof next to Anna to watch for approaching boats. I surface for directions, and Anna points toward the channel. “Five meters ahead.”

Through the splash and glare I locate the shadow still heading for deep water. It’s a big brown beauty trailing eight sausage-shaped feeding tentacles, each the length of my forearm. An entourage of fish races in its wake, their tiny tails thrashing like flags in a gale to keep pace. Unlike the pelagic predator from Ambon with its mop of stinging tentacles, this one is a pastoralist — a primeval farmer packed with enough symbiotic algae to supply its energy needs for a lifetime. It takes all the effort I can muster to catch up with the speedster and stay with it for a few seconds before it zooms out of sight.

From what I’ve been reading lately it’s likely we all will be having more jellyfish encounters in the future. Jellyfish populations are on the rise everywhere, primarily in spontaneous blooms that produce thousands of free-swimming medusas in a matter of days. Although swarms have occurred for eons, the numbers are growing at an unprecedented rate thanks to pollution and global warming — a double-down dream come true for jellyfishes that thrive on eutrophication, acidification, overfishing, agricultural runoff and habitat destruction — the sort of doomsday stuff that sickens nearly every other form of life. If we continue spiraling toward a world that resembles the Precambrian, these ancient time travelers might once again inherit the seas.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2014