They appear without warning. Alien. Impossible. A school of more than 100 hammerheads, like a wall of writhing barbwire, all angles and points. Beautifully sinister, they are hypnotic as they sway back and forth, riding on the sea wind. It’s as if the Arch, 60 feet above, is a gateway from another world.

Through its wave-blasted doors, all manner of marine wonders stream forth. Rivers of fish, including super-sized jacks and mirror-bright bonito tuna, course through the blue. Dolphins and silky sharks are regular commuters, while dozens of huge moray eels slither about the reef. “Mr. Big,” the whale shark, is a high-profile, albeit seasonal, visitor to Darwin’s Arch. The “Enchanted Isles” of the Galapagos have delivered a world-class dive adventure yet again.

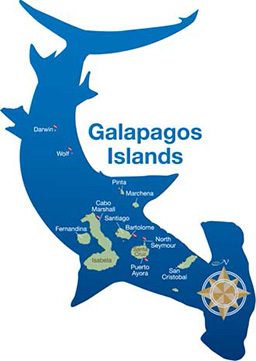

Charles Darwin created the early buzz on this incomparable archipelago 600 miles west of Ecuador, South America. But it is today’s adventurous scuba explorers, those perhaps wishing natural selection had favored them with gills, who have taken this marine reserve viral. Year after year, the Galapagos top the lists of the world’s best dive destinations. For some, the draw is obviously the high-voltage big animals encountered underwater. For others, the topside experience with fearless wildlife and evolutionary oddballs sets this place apart. The menagerie of creatures large and small, temperate and tropical, above and below the waves, surrounded by smoldering volcanoes and surging seas, defines Galapagos.

The Central Islands

Santa Cruz Island is the hub of tourism in the Galapagos National Park. It’s home port for a large fleet of boats specializing in multiday naturalist trips offering snorkeling and hiking excursions throughout the islands. Most liveaboard scuba cruises, however, originate on San Cristobal Island to the southeast.

More than a dozen dive sites ring Santa Cruz. At Mosquera, we drift at 75 feet along a wall of sculpted, carefully stacked boulders resembling a low-budget, Hollywood science-fiction set. It’s adorned with bushes of yellow black coral, and schools of blue-striped snapper and large almaco jacks rush past. On top of the wall, we traverse a broad sandy plain to find both diamond and marble rays, then countless sea stars littered about. Our guide pulls us onward, eventually motioning the group to kneel down quietly so as not to disturb an expansive colony of giant garden eels. They seem caught in a rapturous dance, swaying in the surge as if engaged in some strange religious rite.

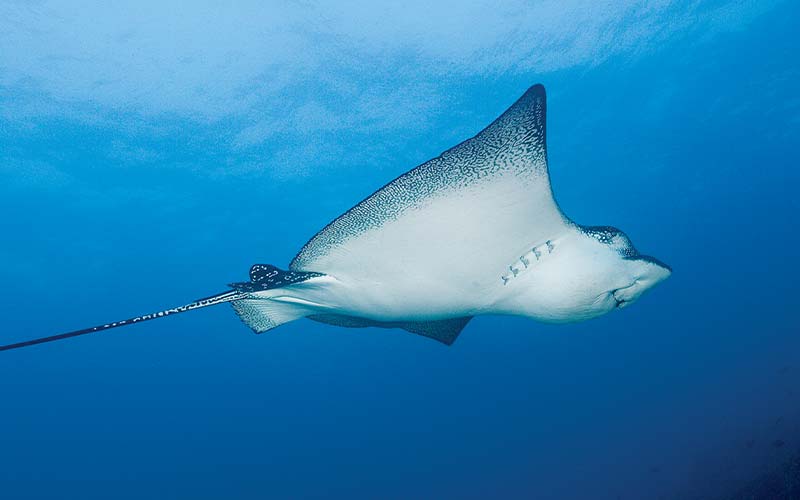

When diving in the central region, North Seymour is a popular choice for big critters in part due to brisk current, which upon striking the island then deviates north. The dive is planned to go with the flow, whisking along in 30- to 80-foot depths over the tops of boulders and beside sculpted mini-walls. Expect abundant marine life, with burrito grunts and yellow-tailed surgeonfish especially predominant. Pelagics, including eagle rays, hammerheads and even mantas, drift in from the blue. Whitetip reef sharks are resident, stacked pell-mell atop each other in lava grottoes.

The beauty of the central islands is the opportunity to exchange split fins for sport sandals to enjoy superb terrestrial excursions. At North Seymour Island, as we exit the inflatable boat to begin our walk along the marked path, we’re unceremoniously met by sleepy sea lions. They open bleary eyes, snort, wiggle whiskers and yawn widely. Then they stare at us. No panicked flight, no signs of aggression. They’re completely unbothered by our proximity. We shake our heads in amazement and snap pictures from a foot away. No need for long telephoto lenses on these wildlife walks in the Galapagos!

Nestled in the scrub further along the trail, proud male frigate birds inflate their shockingly red throat pouches. Marine iguanas crawl out of the ocean onto lava rocks to soak up the sun. The trek’s highlight is witnessing the mating maneuvers of the blue-footed boobies. Staggering about as if drunk, alternating between lopsided high-stepping and contortionist poses, it is an inherently comical courtship.

Weirdness and wonder are all around us. This surf and turf menu, delivering memorable encounters with wildlife in and out of the sea, is one of Las Islas Encantadas‘ strongest assets, contributing to a truly well-balanced holiday.

No expedition to Galapagos would be complete without viewing the giant tortoises for which the islands are named. Galapago is Spanish for tortoise, a species that can weigh some 500 pounds and live up to 150 years. Though we’ve seen turtles (of the green sea variety) on nearly every dive, our first meeting with the islands’ most famous animal ambassador is at the Charles Darwin Research Station (CDRS) in Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz Island. The Charles Darwin Foundation started a captive breeding program there in 1965, and with the help of concerted conservation efforts throughout the island chain, the gentle giants are steadily recovering from the brink of extinction.

Inching our way up the chart, we snorkel with Galapagos penguins at Isla Bartolome. They are the world’s most northerly penguin species and endemic to the archipelago. Don’t pity their inability to fly, because underwater they are rocket ships, zipping about with frantic beats of powerful, stubby wings as they skillfully hunt baitfish. Chasing after these diminutive feathered dynamos leaves me completely spent.

Bartolome offers another opportunity to stretch one’s legs. A short, steep hike to the top of a craggy, dormant volcano affords a breathtaking vista of Pinnacle Rock and a bizarre tableau of lava fields and cinder cones. It’s a postcard-perfect view for fans of violent vulcanism and testament to the nature of the islands’ birth.

Nearby Cousins Rock is a small islet on the eastern side of Santiago Island, and from the air it looks just like a shark’s tooth. Most people choose to dive along a terraced ridge extending off the southern tip, which begins at 20 feet and eventually drops to more than 100 feet. It’s a colorful site, especially on the eastern flank, with ledges covered in glowing yellow black coral, orange cup corals and sponges. Cousins Rock confirms that there’s more than just big stuff in the Galapagos. Frogfish, longnose hawkfish, juvenile king angelfish, bravo clinids, blennies, flatworms, nudibranchs, octopuses and sea horses are just a sampling of the little beasties found here. If you have a chance to dive Cousins Rock twice, put the wide-angle lens back on and focus on the school of barracuda, green sea turtles resting among black coral bushes or the playful sea lions sometimes bold enough to nibble on your fins. Frequently, schools of brown salema, so thick they literally obscure the sun, swim in unison, parting only to avoid the opportunistic sea lions targeting the slow or unfortunate in their midst.

Cabo Marshall, on the northeastern corner of Isabela Island, is a dive that many years ago taught me the wisdom of looking out into the blue. Mobs of fish swarming the shallow reef had captured my full attention, but I was missing the big picture, completely oblivious to the pelagic passersby over my shoulder. My wife practically had to slap me upside the head to get me to turn around. About 400 mobulas, or mini manta rays 4 feet across, filled the water column and darkened the sea. I was so stunned by the immensity of the school that I froze, frantically fumbled my camera, and in doing so nearly missed the shot. It was one of those moments seared into memory, remaining crystal clear after thousands of dives. Cabo Marshall is likewise one of the best places in the Galapagos to see giant manta rays. On my most recent trip, I counted at least five different mantas on one dive.

The Northern Islands

As amazing as all of the above adventure in the central islands may be, two islands far to the north are enough to lure many seasoned divers back to the Galapagos repeatedly. Wolf and Darwin islands are the exclusive domain of liveaboards, considered advanced sites most suitable for those who’ve logged substantial time diving challenging conditions and don’t mind adrenaline overload in the midst of marine megafauna.

A long overnight steam has brought us more than 100 miles to the Landslide at Wolf. The sea’s a bit warmer (about 72°F) and bluer (60-foot visibility) than we had in the central region. There’s a healthy current as expected, so we waste no time in dive-bombing down to the reef, where we promptly grab onto barnacle-covered rocks. Unlike the more placid Caribbean, gloves are a diver’s best friend in the Galapagos. Moray eels, on the other hand, are not necessarily so. The reef is filthy with them, and I have to search for a handhold not already claimed by the overgrown, snaggletooth beasts.

Our eagle-eyed guide’s rattle snaps me to attention, and I squint into the still-dim 7 a.m. water. Spotted eagle rays, a squadron of eight, swoop in close and glide gracefully past. Before they’re even out of range, I hear squeaking and, of course, more rattling. Bottlenose dolphins zigzag toward us, showing off. The next 30 minutes pass all too quickly, with repeated eagle ray flybys, 20 hammerheads, wahoo, bigeye jacks and more.

The peak for me, however, comes on the fourth dive of the day in late afternoon’s gloaming hour, with light levels low and visibility declining. The current picked up, so we speedily drift over the shallow boulder field, enveloped in a frenetic mass of thousands of plankton-picking creolefish. Dozens of green jacks are dining, punching through the creolefish crowds. Marauders, they wreak havoc, tearing through the densely packed biomass. Upping the action another notch, Galapagos sharks join the fray. They are serious sharks, built for business, 8 feet long and thick of girth. They carve through the chaos, hidden from my view one second by the piscine blizzard, then appearing suddenly within arm’s length when the scaled curtain parts. How many are here? Five? Ten? More? Not knowing adds to the suspense and quickens the pulse. I love dives like this.

And then there’s Darwin Island, 25 miles farther north, at the literal and figurative top of the Galapagos chain. There’s really only one dive site off the island, Darwin’s Arch, but it’s a keeper. Almost any pelagic can show up here. Fully briefed and amped up, we take leave of the mothership and pile into Zodiacs. It’s a bumpy ride on 2- to 3-foot waves, with wind and current fighting each other as we near the drop zone. We’re keen to escape the slop, so we quickly count down and backroll into the briny depths. Before I’m clear of the bubbles, I can sense the show has already begun.

We’re directly immersed into a school of steel pompano, flashing like polished silver dollars. A wall of bonito tuna is below and just outside, with a few silky sharks patrolling the perimeter. Powering sideways across the current, we plummet like boobies after baitfish to reach the Theatre, a platform in 60 feet at the wall’s edge. Our shelf offers a panoramic view of the blue; our neighbors are a pair of green sea turtles being cleaned by a crew of barberfish, and plenty of testy moray eels wander about asserting territorial domain. Curious hogfish sidle in close, hoping my death grip on the reef dislodges a barnacle or two. A few Galapagos sharks watch my back from the reef slope. I’m in the thick of it.

The much-anticipated rattle of our divemaster’s shaker is like the dropping of the flag for a nitrox-fueled race. I launch into the blue, sidelong into the current, kicking for all I’m worth in hopes of riding, even if only for a second, the bow wave of the spotted submarine now materializing at the edge of visibility. The titan turns toward us. Time stops. I’m perhaps 5 feet away, dwarfed by its presence. Making eye contact with a whale shark is an unexplainable thing, an out-of-body experience. Then reality rushes back into my brain; the current sweeps me along its flank, and the monolithic tail fin propels it beyond my ability to keep up. It disappears as quickly as it came.

Huffing and puffing, we make our way back to the rocks. I hunker down, daring to hope that I’ve chosen agreeable eels as reefmates, and stare out into the blue of imagination, waiting for the next act to unfold. This is, after all, Darwin’s laboratory, a cauldron of creation. There’s no telling what magic will be served up next.

A few heartbeats later, without warning, the hammerheads are suddenly there again. So alien. So impossible.

All About Balance

The mad rush for Galapagos dive tourism seems to coincide with whale shark season, July through December. The whale sharks are indeed seen along Darwin’s Arch at Darwin Island, sometimes a half dozen on a single dive. Yet the water tends to be cooler then, with a greater possibility for rough interisland crossings. Many savvy Galapagos veterans seem to prefer the prevailing sun and calm weather, not to mention the warmer waters, typical of January through May.

Dive In

SEASONS: Galapagos is a superb year-round destination. Conditions vary widely depending on location and season. January to May is the warm season with air temperatures of 75°F to 85°F with afternoon rain showers but also lots of sun. Seas are generally calm, with 40- to 100-foot visibility; water temperatures average 65°F to 80°F. Some refer to this as the “manta season,” as divers see more mantas and other ray species at many sites. Hammerheads are common, too, though sometimes they stay a bit deeper. June to December is the cooler “garua” season; it’s drier but often overcast and misty or drizzling, with air temperatures ranging between 65°F and 75°F. Seas are rougher, the water is cooler (60°F to 75°F) and visibility lower (15 to 60 feet), but plankton means lots of big animals, including hammerheads, and a very high chance of whale sharks at Darwin.

CONDITIONS AND SKILL LEVEL: Diving is intermediate to advanced due to cooler water, colder thermoclines, sometimes challenging visibility and strong currents and surge. This is not a beginner’s dive trip. Dive within your limits.

GEAR: Depending on the season, full 5mm to 7mm wetsuits are recommended, along with a hooded vest for added warmth. Gloves are also important; grabbing onto rocks to cope with current and surge is proper protocol here. Surface signaling devices are a must.

GETTING AROUND: With 125 islands and islets, there is a lot of territory to explore. Extended liveaboard expeditions are the optimal way to dive Galapagos, and they are the only way to get to Wolf and Darwin. Land-based diving operations are headquartered in Puerto Ayora.

TRAVEL REMINDERS: U.S. and Canadian citizens need a passport but no visa. There is a $100 cash-only Galapagos National Park entry fee and a $25-$40 departure tax when leaving Ecuador. Fly from North America to Ecuador and then out to the Galapagos Islands to board your boat. Check with your boat for details. Pack lightly to avoid excess baggage charges.

Editors’ Note: As this issue went to press, we were advised of a new ruling from the Galapagos National Park Service. It stipulates that a company holding a permit for the Galapagos may choose to conduct either land excursions or diving; there shall be no permits offering both. Dive boats operating in these waters may be altering their itineraries to target the most productive underwater sites now that topside tours are not a consideration for their guests. As a further function of the new ruling, dive boats shall be restricted to three dives per day to minimize impact on the marine environment. Please contact your dive boat or tour operator to confirm their most recent itinerary.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2011