Eighteen years ago, long before the term “Coral Triangle” became commonplace, my partner, David Doubilet, journeyed to Kimbe Bay, a deep basin punctuated by seamounts and surrounded by the active volcanic range that defines New Britain Island in Papua New Guinea. He discovered dense and vibrant coral reefs that reminded him of living, breathing Monet paintings — full of movement, beauty and light. Despite only four days of shooting, this short but intoxicating visit would produce two National Geographic magazine covers.

The richness of the place lingered in David’s psyche for nearly two decades, beckoning him back. We had spent many years exploring the equatorial belt, documenting coral systems in decline from overfishing, physical destruction, bleaching and complete loss of apex predator populations, and David longed to know what had become of Kimbe Bay.

As they say, be careful what you wish for. The phone rang in January 2013; it was National Geographic. David had been selected to contribute to the 125th special anniversary issue of the magazine. He was honored and humbled to receive this “gift” assignment to visually explore a topic or corner of the globe of his personal choice. The good news was that he could go anywhere in the world within reason and budget; the bad news was that the deadline was in early April, three short months away.

Within hours David was on the phone with Max and Cecilie Benjamin at Walindi Plantation, armed with a series of questions: What was Kimbe Bay’s monsoon weather window? Could shore- and boat-based support be available on such short notice? What species were in season? What species would we miss? Could we hope for orcas? Dolphins? David jotted down a reasonable shot list, keeping in mind his theme song, “You Should Have Been Here Last Week.”

We decided to go for it: We were headed to Kimbe Bay for this very special project. I was a supportive but silently reluctant warrior, reflecting on our last expedition to Papua New Guinea barely two months prior in which a colleague was severely mauled by a saltwater crocodile near Madang.

We decided to travel in March and began organizing our gear. We scheduled our trip to miss the heavy monsoon season by enough time to let visibility clear but still meet our April deadline. The schedule was extremely tight, but if we could send images from the site and nothing went wrong, we could just pull it off. This assignment was a gift — a dream assignment. What could possibly go wrong?

Monsoon

The phone rang. Max from Walindi called to tell us to delay our arrival. He said the monsoon season was the worst in decades, and it was causing hell. Buluma Bridge had washed out; access to Walindi Plantation was impossible. We went into standby mode, waiting for the next call while shooting days clicked by.

With the next update we learned it was still raining, but the bridge was rebuilt and passable. We loaded the Land Rover at 3 a.m. and left in the midst of a brutal spring snowstorm on our end. We flew to Manila, Philippines, where we joined our friend and colleague Leandro Blanco, who would be the videographer for the assignment. We flew on to Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, and then descended through frog-strangling rain into Hoskins in the West New Britain province.

Max’s son, Cheyne Benjamin, collected us for the hourlong ride to Walindi Plantation. We were exhausted and quiet, acutely aware that the visibility was shot. Our chances for meeting the April 10 deadline were looking slim, but the anxiety fell away when we stepped out of the van and were greeted by Max and Cecilie. It was a sentimental homecoming for David.

We set up our gear and made a recon dive with Max to scout the inshore reefs. They were as David remembered but, unfortunately, completely out of photographic reach in the runoff-clouded bay. Plan A was falling apart in front of us. We needed a Plan B fast, or we would have to throw in the towel and forfeit the assignment.

Your Camera is On Fire

Exhausted, frustrated and anxious, we retired to our comforting bungalow. David was agitated, wandering around in his boxers and socks, contemplating Plan B. Suddenly, loud shouting erupted from the walkway: “Mr. David, Mr. David, you must come. The camera is on fire.” David burst out of the bungalow in his Bombshell Bettie undies and met Leo, already running, on the path to the camera room. Leo’s battery pack had exploded and caught fire, melting the battery, damaging the housing and destroying the video camera. Theoretically we were lucky because we could have burned Walindi Plantation to the ground if the night watchmen had not detected and doused the fire. The camera room, a wooden structure with a thatch roof, stood within yards of the fuel depot. A few more minutes of unchecked fire would have meant epic disaster.

Plan B was simple enough: Find clear water; make pictures. We hoped the unique underwater topography of Kimbe Bay would save our story and our sanity. We would surrender working on the shallow reefs in favor of the distant offshore seamounts. These underwater mountains rise from the depths, their submerged summits crowned with reef, each distinctive in size, depth and biological complexity. However, diving the seamounts made for longer boat trips and deeper diving, both of which meant less shooting time.

Kimbe Island Bommie was covered in a thicket of mixed corals and sponges. It was an overgrown garden, home to a squadron of barracuda that swam above it like a flock of birds. The bommie was tricky because it seduced us with new rewards every meter. We were in full story mode, passing by interesting creatures in search of the truly bizarre. Nearby Kimbe Island was a superb 10- to 15-foot shallow dive that allowed us to squeeze in more shooting and decompression time.

Skin Bends

Bradford Shoal was entirely different and completely thrilling. This seamount was about barracuda and more barracuda. Hundreds or maybe thousands moved and flowed around the seamount as if in a choreographed sequence. They swam in sinuous geometric patterns and would break to form 80-foot-high towers. We were drawn to them over and over, watching and waiting for the decisive moments in which their patterns changed. I swam along with the moving tower to illuminate the fish and provide a sense of scale for the images. I followed their center as they rose and fell in sync with some secret rhythm. I was careful, but I knew I had pushed my limits. I did not exceed no-decompression limits, but I still chose to spend a long time in shallow water at the end of the dive.

During the 80-minute ride back to shore my arms and torso began to itch and blotch. Leo’s eyes widened as he watched my extremities take on the appearance of marbled steak. I willed it to be sunburn but knew otherwise. I had developed cutaneous decompression sickness — or skin bends. I quickly began breathing oxygen; fortunately, the symptoms rapidly disappeared. The local doctor did not recommend hyperbaric therapy but did advise me to stay out of the water for a while. It was terrible to lose dive days with our deadline looming.

More Seamounts

Joelle’s Seamount is a relatively recent discovery. We slid down the mooring line into a blizzard of fish. The top of the seamount was dotted with cleaning stations. Unicornfish waited in line three or four deep as if at a bus stop. I kneeled to photograph a cleaner wrasse and took a good thump from an impatient unicornfish. Large schools of red pinjalo snapper followed David around like he was the pied piper. They blushed silver, pink, orange and red as they swam by, stalking the weird guy with the shiny Seacam housing. David spent multiple dives with these polychromatic fish, working with shutter speeds to blur colors and create movement. Leo was riveted by the countless huge anemones that would simultaneously ball up to resemble a garden of balloons. Thanks to its isolation, Joelle’s felt like a de facto marine protected area — the fish were fearless.

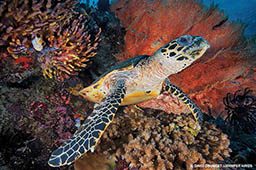

Capt. Allen Rabe invited us onto the liveaboard FeBrina for its return steam from Rabaul to Kimbe Bay. We packed light and flew to Rabaul. The short trip gave us fabulous night squid at Fathers Reefs, silvertip sharks and an incredible hawksbill encounter. Unfortunately, we also got carried away and, trying to move too fast, failed to double check systems. We flooded a Nikon D3S and a GoPro, and we lost a twin set of video lights to the depths. Ouch. Lesson learned.

Malaria

We were making images and sending low-res JPGs to National Geographic each night. The satellite upload process was painful (concluding each evening when the generators kicked off for the night), but our editor was happy. The images coming in from the seamounts looked great, but we needed more of them for the special issue — and we were running out of time.

We were returning from Bradford Shoal, elated after a day of success, when I found myself unable to lift my wetsuit to hang it up. I tried again, failed and asked for help. Humiliated, weak and exhausted, I walked back to the bungalow to rest. I slept through dinner and woke up at 4 a.m., stood up and fell face-first onto the floor. I awoke with my head in a shoe as David gallantly tried to do something to help. Four hours and one blood test later, a doctor in Kimbe declared I had malaria, and I was officially out of the game. I disappeared under a pile of wool blankets and passed out for three days.

I woke up to learn that we did not meet our deadline, and the coverage would not make the 125th anniversary issue. David was beyond disappointed, but he kept shooting; the story would be published in another issue. He and Leo continued working while I crept back toward a new normal and, at long last, was cleared to get back into the water. Cruelly, once the deadline had passed, the rain began to let up, and the images David had dreamed of making began to roll in. For better or worse, the pressure was off, and we could experiment and explore. We began to search for a stretch of coral to create a half-and-half image of the sky and the sea that captured the essence of Kimbe Bay. We swam circles around islands and patrolled shallow reefs but always came up short of David’s vision.

We set off to explore the islands near the tip of the Willaumez Peninsula, which we had scouted by helicopter a few days earlier. It was our last day. It was flat calm, the water was clear, and the sun was finally shining brightly. After a few hours of searching we found a small islet surrounded by a shallow and delicate coral garden. Volcanoes filled the distant horizon, and puffy clouds drifted across a French blue sky. This was the scene David had been seeking since we arrived more than a month before: the perfect interface between air and water that defined the fragile beauty of Kimbe Bay. As we worked, a father and son fishing from an outrigger circled the island and came into full view. David made submerged sounds of sheer joy as he looked through his lens at the scene evolving in front of him. It was a perfect last day on a perfect reef.

Our team had come to Kimbe Bay for National Geographic to explore how these reefs had withstood time in a world of global climate change and uncertainty. For now, Kimbe’s coral community remains robust and flourishing. Sharks, a signature of an intact ecosystem, are here, as are approximately 900 other species of reef fish and more than 500 species of coral. Low human population levels, the historic presence of the Nature Conservancy, the diligent education and outreach programs of local nongovernmental organization Mahonia Na Dari (“Guardian of the Sea”) Research and Conservation Center along with Kimbe Bay’s unique and diverse habitats have all contributed to a thriving reef system in this remote corner of the Bismarck Sea.

Explore More

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2015