“Hiro varoa,” whispered Hobete Ghau confidently in his unique Touo language, “oihare must come up tonight.” For millennia, Hobete’s forefathers in the Solomon Islands had waited expectantly for gigantic leatherback turtles to haul themselves onto the beaches of Tetepare Island. More than half a ton of prized oily meat with the added bonus of at least 100 tasty eggs offer a welcome excuse for a community feast for subsistence farmers who still lack refrigeration or access to food stores. So immense and heavy are these sea turtles that they can be restrained only by a group of men — such as those sitting around Hobete tonight. The laying female had not re-emerged from the pounding waves last night, the 10th night since her last egg-laying, so she would surely appear tonight on the 11th night, known as hiro varoa.

A Darth-Vader-like exhale, audible above the surf, was our first indication that oihare had returned. Ten minutes later, after she had hauled herself up the steep black sand beach and started excavating her nest chamber, Hobete motioned me forward. The menacing glint of moonlight on steel in Hobete’s hand may have suggested a sharp blade for dispatching the turtle, but instead he held a turtle tag applicator. The Tetepare Descendants’ Association (TDA) turtle team measured and tagged every nesting leatherback and relocated all of their eggs to a rookery that was safe from high tides, predatory monitors and the ensnaring roots of beach vines. Last year 1,208 hatchlings emerged from this hatchery — at least 1,000 more than would have hatched without the intervention of Hobete’s turtle monitors.

To finally witness a leatherback nesting was the realization of a decade of dreams for me. While the men worked quietly and efficiently, I was starstruck. The turtle’s massive front flippers, each as long as my arms but many times more powerful, sent sand and small pebbles flying across the beach. Streams of salt-laden tears from her dark round eyes seemed to reflect the exertion and maybe fear inherent to returning to nest on the same beach that she hatched from many decades ago.

The future is perilous for the world’s largest and most ancient living sea turtles, which have experienced cataclysmic declines in recent years. Their critically endangered status is not only due to being hunted and harvested at nesting beaches but even more to inadvertent deaths as fishery bycatch, in boating collisions and through ingestion of ocean-borne pollutants.

Although Pacific leatherbacks range from Canada to Korea to the Southern Ocean, feeding on jellyfish, they only nest on high-energy beaches in the tropics. So fast has been the wave of local extinctions from Sri Lanka to Vanuatu and so steep the declines at once-teeming nesting beaches that scientists have predicted Pacific leatherbacks will be extinct in a matter of years. Only urgent, meticulous care of nesting females, eggs and hatchlings at a handful of sites such as Tetepare is maintaining populations and allowing enthusiasts like me to experience the awesome and humbling experience of witnessing nesting leatherbacks.

Hobete jokes that he is a “spare part” for TDA — a man with many jobs. When the oihare are not nesting, he is employed monitoring green sea turtles in Tetepare’s seagrass lagoons, trochus shells on the coral reefs or populations of the massive coconut crab inside and outside the eight-mile-long Tetepare marine protected area. Once a month he takes his turn with two other rangers to patrol the entire 45-square-mile island, ensuring that occasional fishermen and hunters from nearby islands respect the conservation and sustainable-harvest rules set by TDA to protect their resources. The TDA rangers ensure that traditional owners respect size and boat limits for their harvests and, most important, make sure no commercial operators or poachers access the islands’ rich waters.

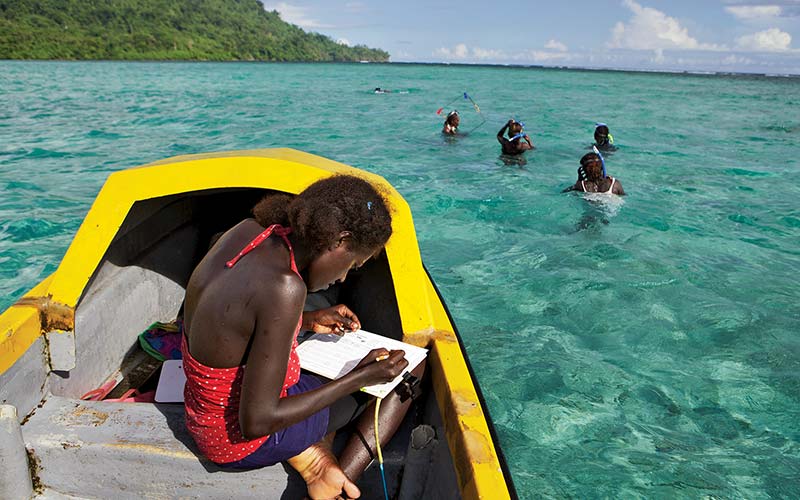

Back near the Tetepare Ecolodge leafhouses (built entirely from traditional materials) another of TDA’s “spare parts” men, Twoomey, is standing up in his dugout canoe, scanning the seagrass lagoon for the telltale signs of vena, or dugong. Twoomey is married to Mary Bea, one of the island’s most influential landholders, who stood up against the unscrupulous logging of her island and instead charted a path for her people to generate sustainable tourism income for the island. Twoomey built the Tetepare Field Station that accommodates visiting scientists, rangers and tourists, but today he is doing his favorite job on the island. Twoomey is the “vena whisperer;” he has gained the trust of the local dugong population so he can quietly paddle one or two tourists out to swim with these inquisitive cows of the sea. There are typically no more than a handful of guests on Tetepare, the largest uninhabited island in the South Pacific, and the dugongs, along with herds of bumphead parrotfish, squadrons of reef sharks and rays, lazing green and hawksbill turtles and myriad brilliant coral reef fish, are unusually blasé toward awestruck snorkelers.

Every visitor not only enjoys an authentic experience on one of the world’s last “wild” islands, but they also support the conservation of the lowland rainforests and teeming reefs of Tetepare through employment of local cooks, guides and boat drivers. Diving at Tetepare can be arranged through Dive Munda and promises great potential in unexplored drop-offs, World War II wrecks and maybe even a village believed to have been cast off the island and sunk by one of Tetepare’s spirits.

TDA has two certified divers, Tony and Mosely, who have acted as guides to divers from cruise boats and yachts as well as researchers who have traveled to Tetepare. The small-scale, locally managed ecotourism and conservation enterprise on Tetepare has now been operating for more than a decade and has become a model for sustainable community-based management of Pacific islands of high conservation value.

The battle to save the forests, cultural sites, reefs and endemic birds, bats and fish of Tetepare from destructive logging is chronicled in the book The Last Wild Island: Saving Tetepare.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2014