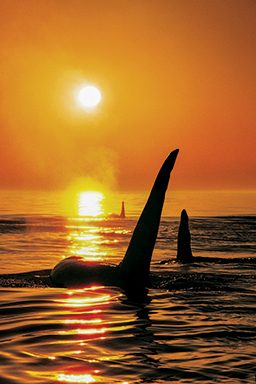

They live in families: pods that each have their own dialect and culture. Over millions of years they’ve evolved a formidable combination of intelligence, power and cooperative social structure that has placed them at the top of the oceanic food chain. The subject of ancient mythology over millennia, they remain one of the most revered creatures on Earth. Yet in 1977 when my friends and I drove from Los Angeles to the Pacific Northwest to photograph orcas for the first time, we knew little about them.

On San Juan Island we visited with Ken Balcomb, one of the world’s leading cetacean scientists, who kindly took us in and pulled back the curtain on the orcas’ world.

Balcomb was one of several pioneering researchers who were cataloging the southern resident orcas that frequent the waters of South Vancouver Island and Puget Sound. With just a glimpse of a dorsal fin’s shape or the subtle shades of a saddle pattern, he could rattle off the designations of orcas like the names of old friends. He flipped through his identification books to show us their family trees, pausing from time to time to point out the quirks of an individual. He explained to us that the J, K and L pods that make up the southern resident population feed primarily on Chinook salmon and, unlike their mammal-eating brethren, spend a lot of time socializing and playing.

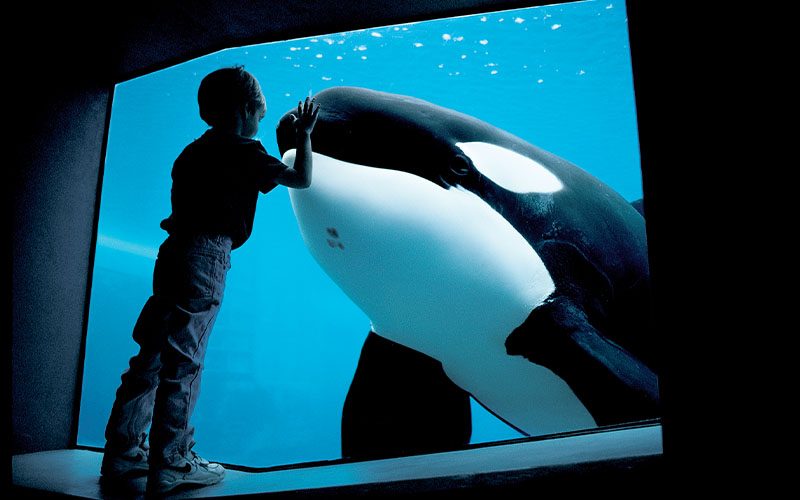

Looking out onto Haro Strait through Balcomb’s living room window, I found it hard to fathom that until just a year before our visit, southern residents were being captured for public display.

Over the next two decades I returned several times to photograph orcas in the waters off northern and southern Vancouver Island.

After the success of Free Willy in 1993, I traveled to San Juan Island again to continue filming wildlife for the sequel. My crew and I were excited by the public’s reaction to the film and elated that there was talk of rescuing the film’s star orca, Keiko, from the subpar facility in Mexico City that held him.

On our first day on the water we were shocked by the scores of whale-watching operations that seemed to have popped up overnight, fueled by the public’s new and growing appetite to see orcas in the wild. I couldn’t help but acknowledge the unintended consequence of the world falling in love with Willy.

By that time threats to the southern resident population of orcas were coming to light. Increased boat traffic certainly wasn’t going to help the situation. The hope was that people’s new affinity for orcas would spur action to address the mounting and much more significant issues of overfishing, pollution and development affecting critical watersheds. Balcomb and others were sounding the alarm, but with the southern resident population still growing, there was little action.

In 1996 Keiko was moved from Mexico City to his newly built rehabilitation tank in Oregon. That same year the J, K and L pods’ numbers began a rapid decline.

In September 1998, fattened up and in good health, Keiko was loaded into a C-17 cargo plane and flown home to Iceland. By the time he was released in 2002, the southern resident population had dropped a staggering 20 percent.

Keiko’s rescue and release were monumental, seemingly impossible tasks. Although Keiko perished a few months later, that effort remains a testament to what we can accomplish through compassion, generosity and hard work.

The public rallied for Keiko because they connected with him through Willy, just as Balcomb and a new generation of scientists and activists have connected to the orcas they’re fighting to protect.

Collectively we took action to correct an easily identifiable issue. At the same time, more insidious problems continued to grow into a crisis that threatens the survival of the southern resident population of orcas.

Chinook salmon, their staple food supply, have been depleted by fishing, dams and other human developments. The din of dramatically increasing oil tanker traffic impedes the orcas’ ability to hunt what fish are left. Starving mothers are metabolizing toxins in their fat stores and passing them on to their nursing calves.

What can we do? Sadly, not as much as we could have done decades ago when researchers sounded the alarm. Our unwillingness to put wildlife and habitats ahead of profits has provided industries a strong foothold.

Today most whale-watching tour operators adhere to strict guidelines, advise pleasure boaters to keep their distance and provide researchers with ID photos. Sightings of J, K and L pods are becoming increasingly rare. The lack of Chinook salmon in the area has forced the southern pods offshore to feed. When they do venture into the Salish Sea, they are much less frolicsome than they appeared in the Free Willy films. There’s not a lot of time to play when you’re struggling to find your next meal.

The resident orcas of North Vancouver Island are faring better as are the mammal-eating Bigg’s pods. Good news to be sure, but as we continue to exploit fisheries, dam rivers and degrade habitats, the next hidden tipping point may soon be upon us.

Shootings and captures wiped out approximately half of the southern residents before full protections went into effect in 1976. From then until the mid-1990s the population rebounded to approximately 98. Today their number stands at 72.

It’s impossible to ignore the magnitude of our failure to act — political half measures and “stocking the pond” to provide a food source of hatchery fish aren’t enough. The very orcas that a generation fell in love with are increasingly unable to viably reproduce.

The only hope lies in learning from our mistakes and acting now to head off future catastrophes. Meanwhile, Balcomb and others who have been fighting to save the southern resident orcas are now faced with saying a long goodbye to their old friends.

Explore More

Learn more about threats to southern resident orcas in this special report video.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2020