The last time I went to the Maldives was in 2010. Although it was a wonderful trip, I felt a nagging bit of guilt about it. At the south end of Ari Atoll is a place where whale sharks come to feed on plankton. It’s also the site of a resort development, and a gaggle of tourists can be found there at any given time. The masses of snorkelers flocking to the few whale sharks in the vicinity create a bit of a melee.

When I was there I swam down to take an upward-angled photo, and when it was time to ascend I struggled to find a spot on the surface free of human bodies or whale shark. It wasn’t lost on me that I was part of the problem — as culpable and frenzied as the rest. In the end I felt bad for the whale shark, which had to deal with so much interference while simply trying to feed.

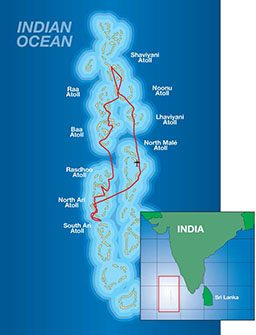

Reliable whale-shark encounters are one of the Maldives’ iconic attractions, but that day I decided that the next time I visited I would find an itinerary that was outside of the mainstream. Fortunately, in an archipelago of 1,192 islands in 26 atolls, there are plenty of options.

Regardless of where you intend to go in the Maldives, your first stop will be the international airport in Malé. From there you’ll transfer to a liveaboard or an island-based resort. With 35,000 square miles of sovereign nation but less than 115 square miles of land, a boat or seaplane will be necessary to get you where you want to go.

This trip was a hybrid of new (to me) areas to the north and familiar dive opportunities in the south that are simply too good to ignore. Even though we boarded our liveaboard in the early afternoon and could have done our checkout dive that same day, we opted to motor north, steaming overnight while we checked into our cabins, assembled our cameras and had our first (of many) dive briefings. This was good, because it allowed us to be better educated about how the geographic diversity of these islands gave rise to distinct and unique reef structures and to learn about the challenges and opportunities each might present.

The channel, or “kandu,” is a deep cleft in the rim of an atoll that connects the inner lagoon with the open ocean. These channels feature swift currents at times, as the tides move massive amounts of water through these relatively narrow openings. They are best dived during incoming tides when clear water streams into the lagoon (and if a diver is swept beyond the intended pickup, it will be into the shelter of the lagoon rather than the open ocean). Our group of dedicated underwater photographers groaned audibly when presented with the possibility of diving in heavy currents, as they make composition difficult, but not all divers share this concern, and diving in the current can be a rush.

A “faru” is a circular reef that rises from the ocean floor within a channel. Featuring ledges and overhangs where marine life congregates, farus tend to attract pelagic life because of their exposure to currents.

A “thila” is a shallow reef within an atoll — like a small seamount that rises from a 20- or 30-foot seafloor. Because of the influence of tidal currents, significant coral and fish life may be found on thilas. Thilas and farus are relatively easy dives, mostly free of current and easily well suited to multilevel diving or prolonged ascents.

The Dives

Our first dives were at Lhaviyani Atoll. We descended on Fushifaru Kandu at slack tide, which gave us the opportunity to effortlessly navigate the shallow reef, but the water clarity was worse than it would have been in an incoming tide. No matter, the attraction here was schools of reef tropicals so massive they obscured the water.

I was initially surprised to find such a large congregation of redtail butterflyfish (Chaetodon collare), as I’d forgotten how common they are in the Maldives. We found them pretty consistently throughout the cruising range, mostly as singles or in pairs, but on this reef they were present by the dozen. We also saw bluestripe snappers in large schools at several bommies throughout the trip; here they were comingled with schoolmaster snappers.

Turtle Cave was a site that came by its name honestly. The crew briefed us to expect green sea turtles throughout this dive, but they really undersold it. The site seemed fairly underwhelming at first — just a sloping reef populated by the usual Indo-Pacific suspects. But then we drifted into a portion of the wall with small pockets and overhangs that must be highly attractive for resting turtles, because they were literally everywhere. I don’t know if I saw 24 turtles or the same dozen twice, but it was incredible how abundant and mellow they were. If I never took another turtle shot the whole trip (though I did, of course), I would have been happily satiated after this dive. Once we drifted out of that portion of the reef, things got pretty tame again. But in that spot, Turtle Cave was world-class by any standard.

Our next stop was Shaviyani Atoll. At Danbu Thila the most compelling feature was a large congregation of extraordinarily friendly batfish. We dropped into the water upcurrent of the reef structure, and the first thing we saw were batfish swimming right up to us in crystalline visibility. I think most of us maxed out our bottom time at 80 feet working with the batfish only to have them follow us into the shallows at 30 feet. Their behavior was the same throughout the dive, but the attractive reef backgrounds in the shallows made for even better images. If I never took another batfish shot the whole trip (though, again, I did), I would have been happily satiated after this dive, too.

Up until we dived Eriyadhoo Beyru we hadn’t seen much soft coral on the northern reefs — I was actually surprised by how low-profile the decoration on the walls was. The soft coral was dense, and it made for wonderful backgrounds for fish photos, but I had the thought that if I were to photograph a diver against these soft corals and wanted to make the corals appear impressively large then I’d need to book Ant-Man as the model. That didn’t diminish my appreciation of the thoroughly beautiful and productive dive, but it was one of those random thoughts that passed though my mind during the safety stop. Later I searched online for “soft coral in the Maldives” and found plenty of contemporary photos and videos of reefs draped in soft coral, so I won’t project my experience on this reef to the broader Maldives underwater experience. Nor is the soft coral the only attraction here: The hard corals, particularly the staghorn variety, were vast and pristine. The contrast of the orange anthias amid the golden branching corals was particularly inspiring.

At Noonu Atoll’s Raafushi Cave, my most significant photo opportunity was with a giant moray at a cleaning station. A school of orange anthias swam close to the eel — perilously close, perhaps, but I suppose such a large eel might be pretty ponderous in pursuit of a nimble anthia. Anyway, I saw no evidence of any fish being alarmed to swim near the cavernous eel maw.

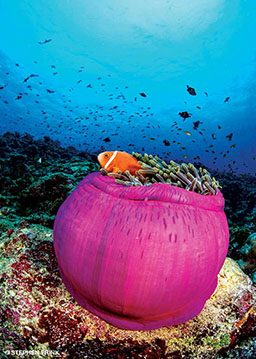

The next day at Raa Atoll I saw Nemo City on the briefing board. Having dived many sites called “Anemone City” or something similar, I am rather desensitized to such names. In fact, I’d forgotten the name of the reef until I began seeing lots of anemone clusters, many of which were curled up with their crimson or lavender mantles exposed and the resident endemic Maldives clownfish within. It was really quite beautiful, and once again I felt the dive was more significant than I had expected.

Baa Atoll is most famous for the large aggregations of manta rays and whale sharks that frequent Hanifaru Bay between July and November each year. Being there on Valentine’s Day I realized I wasn’t likely to get much manta love, but I found other things of interest. The dive that most resonated with me was Horubadhoo Thila — the fish were especially friendly there.

There are 32 marine protected areas in the Maldives. The expanses of reef they cover are not necessarily large, but the dive sites within them are especially vibrant. These are total no-take zones, and because the dive operators are there so often, they are self-policed. Here I saw surgeonfish calmly being cleaned and emperor angelfish boldly swimming toward my dome port. Had I not already been told about the protected status of this reef, I would have known based on the behavior of the marine life.

With five days of diving under our weight belts, we headed southward to some of the most iconic dives in the region. The first was at North Ari Atoll among the sharks of Rasdhoo Ridge. Here we dropped onto the ridge, which topped out at about 60 feet, spread out and waited for the gray reef sharks swimming in the blue to approach us. We were advised to not swim toward the sharks, as this tends to keep them away; gratefully, everyone rigidly adhered to the directive. The result was sharks that came within 6 feet of us and occasionally as close as 4 feet. There was no bait in the water, just a calm interaction with a beautiful species of shark.

The day began with a high-voltage shark dive and ended with a mellow night dive at Maaya Thila. Rising to a depth of 22 feet, this thila was small enough to circumnavigate a couple of times in the course of a 60-minute dive. The most significant photo ops were sleeping turtles, marbled rays, free-swimming morays and lionfish.

Fish Head is another marine reserve, also on North Ari Atoll. The site was named during an era when local fishermen were likely to bring nothing but a fish head onboard, so ravenous and plentiful were the sharks. While the area may not be as shark infested as in days of yore, we were still able to perch atop a rocky knoll at 60 feet and watch a half dozen gray reef sharks pass to and fro, edging ever closer as we remained motionless. A massive school of bluestripe snapper was at 90 feet, and were I not reluctant to have my bubbles disrupt the shark action, I would’ve loved to drop into their midst. But it was just as well — at the top of the reef in only 30 feet of water was another school. Once I’d filled the frame with 100 fish, it didn’t really matter that there were 500 somewhere else.

We had come southward specifically for manta rays. At certain times of the year mantas are abundant in the north as well, but this was February, and the dive staff knew that for us to interact with mantas we would do well at the manta cleaning stations at North Ari Atoll. The first we tried was Himendhoo Rock. The plan was to swim to a small coral bommie that hosted the cleaner wrasses that drew in the mantas. We saw one manta on a flyby, but despite the frequency of success others have enjoyed at this site, lovely reef tropicals were all that populated my image download. It was the same story on our second dive at Moofushi Rock: The visibility was marginal, and the manta action was sparse.

That changed the next day at South Ari Atoll on Rangali Madivaru (“madivaru” means “ray” in the local language, appropriately enough). We swam along a shallow sloping reef that featured incredible manta activity — in terms of both the number encountered and the ease of proximity. Everyone in the water had wonderful close encounters with the rays and captured images with two or three in the frame. As if to underscore how special this dive was, our second dive on the site three hours later featured a few encounters but nothing at all like the rich rewards of the morning. Whether the tide or the current or karma was the differentiator, the lightning in the bottle on that morning dive had escaped by noon.

Maldives reprised was a great success. We hit our marks. We found the iconic mantas in the south and enjoyed our time in the north as the only liveaboard on the horizon. We didn’t get a whale shark encounter, but on balance that was fine with us. I doubt the whale sharks missed us very much either.

How to Dive It

Temperature: Expect air temperatures of 79-86°F and water temperatures of 82-85°F year round. A 3mm wetsuit is generally sufficient, even for four dives per day.

Currency: Get just enough Maldivian rufiyaa (MVR) for island tipping and pocket change. Most restaurants, hotels, car-rental companies and shops accept major credit cards. Banks accept 2004 or newer U.S. dollars and euros with no tears, rips or markings.

Seasons: The prime diving season is from November to April, although dive tourism is now a year-round attraction.

Dhoni Diving: Most liveaboards operate in tandem with a traditional dhoni, typically a 50- to 60-foot yacht with diesel engines that houses the compressors for air and nitrox fills as well as most of the dive gear (though not cameras). Guests step from the mother ship to the stable and spacious dhoni (usually in calm water) for transport to the nearby dive site.

Currents: Each diver should carry and know how to deploy a surface marker buoy. Also recommended are a personal air horn, mini strobe light and a radio or GPS locator. Most divers carry a reef hook as well.

Alcohol: Alcohol is generally prohibited in the Republic of Maldives. There are no liquor stores or bars where it can be sold or consumed, and tourists may not bring alcohol into the country with them. All incoming luggage (including carry-on bags) are X-rayed, and authorities will confiscate any liquor found. There is a specific exception for licensed tourist operations catering to international clientele.

Depth: By federal law, scuba divers may not dive deeper than 30 meters (98 feet). This tends not to be a problem because the seafloor at most dive sites is around that depth.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2016