In the approaching distance, we see a splash and then another.

“What is that?” asks my dive buddy. We’re perched at the front of a small boat, headed from the mainland of Moalboal, Cebu, toward nearby Pescador Island. We have hit it just right — a sardine run began just before we arrived, and there are reports of huge bait balls at our planned dive site. “Is that a mobula ray jumping?”

We watch as the animal heaves itself out of the ocean once again.

“No…” he says in a quiet, almost reverent voice. “Look at that tail. It’s a thresher!” A hush falls over the boat as we watch, amazed, a thresher shark repeatedly breaching, its characteristic tail arching away from its body like a long whip. After a few minutes, the silence is broken by several expletives, as the realization dawns that not one of us has a topside camera. We’re incredulous and moved, and it’s clear that plenty of mental imaging is taking place.

The Visayas: Bait Balls, Muck and More

We have come to the central Philippines not really knowing what to expect. Our liveaboard originates in Dumaguete on Negros Island, but we have decided to fly directly to an adjacent island, Cebu, for a few days of land-based diving before we meet the boat. That decision was easy, but figuring where to stay on Cebu was the hard part. Malapascua, renowned for thresher sharks, was one attractive option. We knew we wanted a mix of boat dives and shore dives, small creatures and big reefscapes, so after a little guidebook research we decided that Moalboal, on Cebu’s southwestern coast, fit the bill.

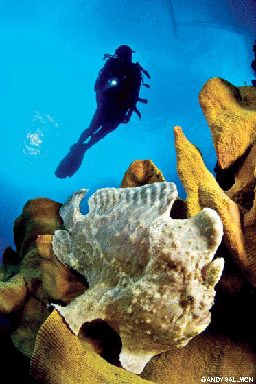

It was a good call; we spent most mornings diving Pescador Island, where we encountered the sardine run. Although we weren’t fortunate enough to view any thresher-shark action underwater, we were treated to massive schools of sardines blocking the sun over huge barrel sponges and sea fans dotted with crinoids of every imaginable color. Afternoons were spent on the reefs off Moalboal, searching for turtles and giant frogfish or simply admiring the lush soft corals that jut abruptly from the ocean floor. Night dives were done on our resort’s house reef, an easily accessible wall boasting lots of miniature life, including ornate ghost-pipefish, nudibranchs and a massive variety of shrimp.

Days later, we met our liveaboard at Dumaguete. Once settled onboard, we promptly geared up to explore nearby Atlantis Dive Resort’s house reef, a rubbly stretch of hard coral surrounded by the stark, black sand that is characteristic of this part of the island. At first glance the seascape was underwhelming, but seconds later our first hairy frogfish came into view and our perception was transformed. This sighting was quickly followed by a sea horse, a harlequin ghostpipefish, a flamboyant cuttlefish, multiple nudibranchs — you get the idea, and we got the pictures.

Dumaguete is the muck-diving capital of the Philippines. Pygmy cuttlefish and juvenile sweetlips are seen everywhere, hovering adjacent to rubble and rocks, and the bottom itself is dotted with cockatoo waspfish, snake eels, Pegasus sea moths, a variety of scorpionfish and stonefish. The dive site Cars, so named because of the odd wreckage of a Volkswagen Beetle providing refuge for frogfish and lionfish, became the favorite of our fellow passengers.

When we got tired of diving the muck, there was an easy solution. Nearby (an easy day trip for divers staying in Dumaguete) is Apo Island, and the difference in topography is night and day. Apo is home to untouched hard corals and sea fans as well as scorpionfish, numerous grouper and moray eels, plus lots of small stuff like crabs, shrimp and gobies. Nudibranchs are also a common sight, but the reefscapes are the highlight.

From Dumaguete and Apo Island, we headed northeast toward Bohol and spent an amazing day diving the reefs of Balicasag. These slopes and walls boast a variety of soft corals, gorgeously colored anemones with resident anemonefish and gorgonians. Green sea turtles are seen regularly, and small schools of mackerel hang in the blue. On one dive, several of us were chased by an aggressive titan triggerfish guarding eggs, a sight one diver didn’t notice until — too late — he got a warning nip on the leg. We did a few more dives off Bohol’s Alona Beach, a marine sanctuary that yielded fantastic opportunities for macro photography, including starfish with commensal shrimp, crocodile flatheads, gobies and blennies.

Our next stop was Cabilao Island, a small landmass between Cebu and Bohol marked by a large lighthouse. The steep walls within the marine sanctuary here boast mind-blowing soft corals in every color, red sea whips crawling with crinoids, large fans containing pygmy sea horses and schools of mackerel and bigeye trevally — as well as the best visibility of the whole trip. When the wind came up in the afternoon, our captain navigated away from the lighthouse and into a small bay adjacent to the village of Cambaquiz. My buddy and I looked at each other with disappointment, but then we noticed the dive guides grinning at each other. We entered the water to discover an amazing white-sand muck site, and within minutes one of the guides was banging his tank frantically to alert us to the presence of his first notable find — a wonderpus. We also saw flying gurnards, a variety of tiny shrimp and crabs, razorfish and scorpionfish. This dive ended up being our longest of the trip; we stubbornly parked ourselves at a shallow part of the site until all the other divers were long gone and we could hear a skiff motoring impatiently back and forth waiting for us to surface. By the time we exited the water, night had fallen, and our fellow passengers teased that they had already eaten dinner without us. Fortunately, they had saved us a little.

When we left Cabilao, we were convinced that we had seen the best of the Visayas. The boat was headed south toward Hagakhak, in Mindanao, and we went to bed that night a little depressed — we hadn’t heard anything about that area at all and didn’t have high hopes. As it turned out, our concern could not have been more unjustified. We woke to discover that we were anchored in a picturesque bay lined with small, white beach-rimmed islands, and there was not another boat (or person) in sight. Over the next two days we were treated to an unbelievable variety of marine life and reef scenery. Hagakhak offers steep walls covered with hard and soft corals, sloping reefs with swim-throughs, sea snakes, a variety of moray eels and a few jellyfish. Of the reef’s minutia, we saw nudibranchs, cowries, numerous wire coral shrimp and gobies, and we even came across a blue-ringed octopus. The diving here was so magical that several of us badgered the crew into dawn dives two mornings in a row.

From Hagakhak, we sailed toward the southern part of Leyte, near Sogod Bay, a place where snorkelers can reliably, albeit seasonally, swim with whale sharks. We dived the Napantao marine sanctuary reefs of nearby Panaon Island and spent the morning happily photographing massive schools of anthias and fusiliers swarming over green tubastrea coral.

In the afternoon, we explored a jetty adjacent to the village of Padre Burgos on Leyte Island. We entered the water with muck diving in mind and our cameras set up for macro photography, but as soon as we descended and glanced back at the surface, we experienced a deep pang of regret at our lens selection. Sun rays pierced the water, while baitfish swirled in the distance; branches of soft coral hung from the pilings. It was wide-angle heaven, but it did deliver some opportunities for close-ups, too. A careful look at the pilings revealed nudibranchs everywhere and a variety of frogfish, blennies and lionfish. Sea horses clung to debris along the bottom. Small clusters of staghorn coral adjacent to the jetty held a small population of mandarinfish, which are a major draw for photographers at dusk. The offshore reef diving we did in Leyte was also phenomenal, allowing us to spend our final hours in the Visayas photographing large gorgonians and schools of anthias moving fluidly over hard corals.

We spent the afternoon sailing back to Cebu, enjoying the sunset and admiring our fellow passengers’ photographs. We couldn’t help being just the slightest bit smug. We thought we were taking a bit of a chance going there, but we discovered that the Visayas may be one of the best-kept secrets of Southeast Asia.

Verde Island Passage: Anilao and Puerto Galera

David Behrens, one of the best known nudibranch researchers in the world, in his recently published Indo-Pacific Nudibranchs and Sea Slugs, identified the Verde Island Passage as the “center of the center of marine diversity … the apex of the Coral Triangle,” a glowing review by any diver’s standards.

Nearly a decade before this field guide was published, we heard rumors about the incredible density of marine life that could be found in those waters. Over the past couple of years, however, the rumors turned into incessant eyewitness reports from people we knew and trusted. Amazing images emerged of the undescribed nudibranchs they had discovered, a shrimp they had waited their whole life to see, rhinopias at every dive site and more. At first we were just plain jealous. Over time, however, our jealousy matured into pity — poor Anilao and unfortunate Puerto Galera, to be typecast in such an unjust manner, known solely for phenomenal diversity of tiny critters. We resolved that when we visited this region, we would challenge the macro-only stereotype (or at least give it a solid attempt).

So upon our arrival in Anilao, we dared our divemaster to show us the best wide-angle vistas the area had to offer. He gave us a big smile and a nod, and we got the distinct feeling that we were in for a surprise.

That’s how we ended up spending our first dive in Anilao mesmerized by dense swarms of anthias at Beatrice Rock, a dive site populated by scorpionfish and giant frogfish living among barrel and vase sponges, crinoids and multicolored tubastrea, often open due to the ripping current. Modeling for each other here was truly a challenge; it put our fly-by posing skills to the test. Subsequent dives at other sites further convinced us that Anilao was home to fabulous, unsung wide-angle vistas at Ligpo Island and Twin Rocks.

Any who come to this area searching for critters are going to be blown away. Anilao’s Secret Bay, a classic muck site complete with volcanic sand bottom, is famous for its macro offerings. A series of dives here revealed nudibranchs, frogfish, ghostpipefish, a wonderpus, a mimic octopus and a wide variety of crabs and shrimp. Off nearby Maricaban Island, the dive site called Bethlehem is renowned for rare and beautiful nudibranchs and is the site of discovery for several new species. However, any site in Anilao seems to yield amazing life, including many jawfish (often with eggs) and fire urchins populated with Coleman shrimp.

Don’t expect huge hotels or a bustling nightlife in Anilao. It’s made up of a series of small dive resorts, often family owned and visited mainly by divers from nearby Manila. However, if your idea of dive-vacation heaven is diving (interrupted only by eating and sleeping, with the latter being optional in lieu of more diving), then this is where you belong.

On the other side of the Verde Island Passage lies Puerto Galera, arguably more well-known and popular among visitors from the United States and Europe. Like Anilao, there is plenty of talk about the critter diving here, but not much is heard about its underwater scenery.

This seems a little odd when you consider that the most famous dive sites here are three wrecks — two small wooden vessels and a sailboat — located just off Sabang Beach. The Sabang wrecks are loaded with marine life, most notably large frogfish so perfectly posed on upper decks and railings that we couldn’t help referring to them as supermodels. Several other wrecks and some natural reefscapes are also available; nearby Verde Island’s above-water peaks give way to steep underwater dropoffs covered with large sea fans and gorgonians and inhabited by batfish, turtles and barracuda.

Like Anilao, Puerto Galera’s reputation as a critter haven is well-earned. Some of the best small marine life can be found immediately offshore in Sabang Bay, minutes away from most of the resorts. Among the sand and rubble are Napoleon and crocodile snake eels, ghostpipefish, flying gurnards, nudibranchs and frogfish. The Sabang moorings are a popular site for night dives and a common place to spot stargazers and a variety of lionfish. Sinandigan Wall is home to (surprise) tons of nudibranchs, so many that our group nicknamed it “Nudi Wall.” Manila Channel is a good bet for finding pygmy or flamboyant cuttlefish and the odd-looking devil scorpionfish.

The Dive Season

It is generally agreed that the ideal time to visit the Philippines is from April — after the windy, dry season ends — through June, before typhoon season starts. Popular destinations such as Anilao, Puerto Galera and Dumaguete are busy year-round. Water temperatures range from the mid-70s in winter to the low-80s in summer.

From the Visayan Sea in the central Philippines to the Verde Island Passage up north, this island nation treated us to a fascinating variety of underwater experiences and images. At the end of our visit, the ride back to the Manila airport was occupied by a playful argument about whether the tiny critters were most impressive or whether the reefscapes, massive schools and marine vistas took the cake. Eventually we reached an impasse, which brought us to this point — do not be fooled into thinking that size matters when it comes to the underwater world of the Philippines.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2011