Advances in the design and mass production of self-contained underwater breathing equipment in the 20th century enabled every person interested in diving to do so, especially for recreational purposes. For several thousand years before that, though, diving was an extreme activity practiced exclusively by elite athletes, and even then it was only if they had existential reasons to do it. But nobody practiced it for a lifetime like Greek sponge divers did. What we know about them has been passed down mainly through oral histories, and often the line between truth and legend is blurred.

As the story goes, Greek sponge divers worked at depths of 100 to 200 feet, staying underwater for two to three minutes on a single breath. They feared nothing: not the depth, the dark, the giant octopus or the shark. With a long history of collective experience, daily practice from early childhood and a culture of heroism, sponge divers were proud and revered providers in the subsistence economy of their communities. However, the same experience and pride that made them heroes also made them vulnerable to the technological advances and trade expansion in the 19th century.

The Naked Gymnasts

Until the advent of scuba gear, diving was defined and limited by the physical ability of the “naked divers” who practiced it. Inhabitants of the barren and arid Dodecanese Islands, whose economy depended for centuries on diving, were among the best in the water. The brothers Sarandaki from the island of Symi are remembered in legends as “gymnasts” able to dive to 40 fathoms (240 ft). A name still heard today is that of Georgis Stathis Hatzis, who found the anchor of the Italian battleship Regina Margherita in 1913. His tale is not the stuff of legend but of truth, and his feats are well documented. He was described as an older, feeble man with pulmonary emphysema who couldn’t hold his breath at the surface for more than 40 seconds. Despite that, after a few work-up dives Hatzis was able to find the anchor 250 feet deep. His final dive lasted three and half minutes.

Hatzis’ technique of “work-up dives” is known today to improve the capabilities of divers through various short-term physiological adaptations such as the spleen sending extra blood into the circulation to increase its oxygen-carrying capacity. Obviously, sponge divers learned it empirically at some stage of their long history. Even as far back as the time of Aristotle, divers were able to exceed depths of 200 feet and bring back information about the water temperature of the Mediterranean Sea. Throughout the Hellenic era, divers were a stealth force in naval warfare. Both commercial and military divers have been mentioned in classic Greek literature, but detailed accounts of their activities practically did not exist until two centuries ago.

In 1850, a young British naval officer named Frederick Walpole observed Greek sponge divers in Northern Africa. They dived deep but not for more than 27 seconds at a time. In Walpole’s view, they did not impress. He recognized their method of diving as similar to that of Japanese ama and Korean divers, which, while admirable, is still within the physical limits of average people. But at the time, the demand for sponge was so large there were not enough skilled divers to generate the supply, and captains hired anybody who was willing to try. Most of them quit within a year.

In contrast, the naked divers observed by Capt. Thomas Spratt in 1885 while en route to Crete mainly originated from the Dodecanese Islands. They displayed much more impressive athletic abilities. According to Spratt’s measurements, they dived to depths of 180 feet and stayed as long as 90 to 120 seconds. Spratt noticed that before each dive, the divers practiced some kind of mental exercise followed by a few minutes of hyperventilation. They did one dive at a time, 15 to 20 times a day and were assisted by surface tenders. Spratt estimated the number of sponge divers in the region at about 3,000 and number of deaths at no more than five to six per year.

Boat-Men and Machines

In 1865, the first hard-hat suit called a scaphandro (boat-men) was brought to the Dodecanese Islands. This “machine” enabled even mediocre divers to extend their stay at the bottom by breathing surface-supplied compressed air. Within just a few years, Greek sponge divers introduced the scaphandro en masse and harvested unprecedented wealth from the depths. This was years before Paul Bert associated decompression sickness (DCS) with gas bubbles or Haldane published the first decompression tables. The divers paid a horrific price for their ignorance; in the first 50 years of scaphandro use, some estimates put the toll at 10,000 fatalities among Mediterranean divers. They were undeterred though, and the sponge trade continued to flourish. Economic pressure and pride pushed the divers on despite the high odds of catastrophic injuries.

In 1867, according to French Navy physician Le Roy de Mericourt, the suppliers of the machines reported that out of 24 divers using 12 scaphandros (two divers per machine, each doing multiple dives a day), 10 died during the season. Three of the ten died immediately after surfacing, and seven died of complications caused by paralysis. The 42 percent fatality rate was higher than any rate found in wartime.

Some divers went to depths of 146 to 175 feet. The inventor of the equipment, Auguste Denayrouze, cautioned against going deeper than 123 feet or exceeding 2.5 hours underwater per day. He warned that the ascent must be very slow and recommended a rate of three feet per minute. But it was impossible to get divers to comply. Two thousand years of breath-hold diving experience taught them to get back to the surface as soon as possible. In addition, they may have been listening to some contemporary “authorities” who reasoned that compressed-air divers get injured during ascent and thus should keep it as short as possible.

In 1868, a young Italian doctor, Alphonse Gal, traveled to Turkey to observe sponge divers. That year there were 10 suits at Kalymnos alone, but there were three divers employed per machine, 30 divers total. That season ended with two deaths and two paralyzed divers. In 1869 there were 15 suits, and the annual toll on the more than 45 divers was three deaths and three cases of paralysis. The fatality rate was dropping, and the improvement was ascribed to the increased number of divers per scaphandro, which reduced each diver’s daily bottom time.

Over time, knowledge about the causes of decompression illness and safe decompression improved, but casualties among Greek sponge divers did not change much. In 1910, the Greek government stepped in, established schools for divers and regulated many safety aspects of diving. Each dive boat had to have a sufficient number of divers to minimize repetitive dives. Captains were obliged to use decompression tables and, in cases of bends, to attempt in-water recompression. Dive boats had to have at least two lead tanks with compressed oxygen for first aid purposes.

The government oversight of sponge diving did little to improve casualty rates; in 1965, Russell Bernard reported numbers similar to those of a century before. From 1950 to 1969 there was an average of 40 boats (300 total divers) at Kalymnos. In the same period, 167 divers were paralyzed and 48 died. But the statistics reveal only the catastrophic injuries; indeed, divers regularly suffered a variety of symptoms. What they suffered is not unlike the similar devastating consequences experienced by the lobster fishermen of Honduras’ Miskito coast. In both cases, economic pressure forced divers to disregard safety measures. Bernard detailed further factors in his anthropological study, Sponge Fishing and Technological Change in Greece (1987). A system of platika, or advanced payment, made divers indentured servants and captains cruel masters. The honor system and the imperative to live up to their reputation forced divers to go far beyond safe limits to fulfill what they had promised.

Theirs is a rich history, and a lot is said about the courage of sponge divers, their readiness for sacrifice and their willingness to take risks. In learning about them, I decided I wanted to meet them personally.

Meeting The Last Living Sponge Divers

I began my search in Tarpon Springs, a small, picturesque town on Florida’s west coast. At the beginning of the 20th century, blights destroyed overseas sponge beds, creating an opening for Florida sponges. Greek sponge divers were invited to help with the harvesting, and using traditional scaphandros they were able to gather a great deal more sponge than local harvesters who deployed their tools from the surface. As the Florida sponge industry grew, so did the colony of Greek sponge divers; Tarpon Springs soon became the “Sponge Capital of the World.” The industry flourished until 1985, when blights spread to Florida, too.

At the peak of sponge fever, the fleet of harvesters in Tarpon Springs numbered up to 100 boats and 1,000 divers. When I visited in 2010, there were barely 10 boats engaged in part-time sponge diving. The local economy, however, still benefits from the sponge industry. Between several sponge factories, the old sponge exchange and a museum, visitors still learn about the history, harvesting, processing, trading and use of sponges. A fleet of tirhandils, traditional Greek boats built on Florida shores for sponge divers, will take you on a demonstration dive with a hard-hat diver. You can scuba dive with local guides and observe sponges in their habitat. The original Greek food and colorful Greek festivals alone are worth the trip.

I was introduced to George Billiris, a local community leader and promoter of sponge-diving-related businesses. He had started his career as a deckhand on his father’s boat, working his way up to diver and, eventually, captain. He had unique insights into the mind of a sponge boat captain.

Sponge boat captains were, in the first place, entrepreneurs. They cared about the safety of their divers, but that concern came behind others, including how to procure funding, choose the best sponge grounds, ensure productivity, bring harvest home and get it to market. Florida waters were kinder to divers, and they did not suffer the plague of injuries their predecessors in Mediterranean waters did. The demand for sponges seems to be growing again, and Billiris is looking forward to employing new diving technologies to re-establish the sponge industry. I wanted to know more; Billiris advised that if I really wanted to learn from those who lived the history, I needed to visit the Dodecanese Islands.

Tale of the Turkish Diver

In September 2010, I learned that the most famous Turkish diver, Mehmet Aksona, was due back in his home of Bodrum after spending some time away revisiting the Mediterranean banks where he’d harvested sponges 50 years ago. Kalymnos, the famous island home of Greek sponge divers, is only about 15 miles off the Bodrum coast. I was due to attend a medical conference in Istanbul; the timing was ideal for a pilgrimage to the historic sponge-diving areas.

Turkey ruled the Dodecanese Islands until after World War II. Turkish authority left Greek islands a significant autonomy but required that Greek captains include Turkish apprentices in their crews. Connections between islanders and shore inhabitants did not completely cease even after the islands returned to the sovereignty of Greece. Mehmet, born near Bodrum on the Turkish coast, started his apprenticeship on a Kalymnian sponge boat in 1965. At that time, the beaches of Bodrum Bay were lined with a single row of small, white fishermen’s houses. Today, the restored Bodrum Castle stands out above the forest of tall masts rising from the clusters of shiny boats that cover every inch of the bay in the heart of the large resort town.

Finding Mehmet was not a problem. His 60-foot, two-mast sailboat, an enlarged version of a classic Phoenician tirhandil, was in port. With a large banner reading “Aksona Mancorna II Cruises,” I couldn’t miss it. I couldn’t miss Mehmet, either. Slim and straight, the 60-year-old captain has a wide, warm smile that softens a face full of deep carvings earned by a lifetime on the sea under the hot Mediterranean sun.

He took me on a short walk down the pier and proudly showed me the first Aksona Mancorna, a typical sponge-diving boat some 24 feet long, still in perfect sailing order. With this boat, a crew of seven and several harvesting campaigns in North Africa and Sicily, he made enough money to build a larger boat and catch the wind of tourism that began to flourish as the sponging was coming to its end. Diving remained his love, though, and Mehmet was a champion spearfisherman. Every moment with him was a lesson in the history of sponge diving. Aboard his boat, he fed me a festive version of a typical diver’s meal: a peksimet, or a bread with seven crusts divers used to carry with them. Hard as a rock, we soaked ours in kakavia, or fresh grouper quickly boiled in a handful of water and olive oil. With a few sprigs of fresh herbs, it was a perfect and memorable meal. The stories were even better.

Mehmet learned his skills from a captain formally trained as a diver by the Turkish navy. His captain taught him, “The most important thing in diving is to adhere to aksona — decompression rules.” He dived using a Fernez, a kind of surface-supplied equipment. Though he never experienced a major incident himself, Mehmet saw quite a few injured divers. “If you want to take too much from the depth, you pay the price,” said Mehmet, a fervent advocate of sustainable exploitation and the protection of natural resources. On his last trip to Sicily, Mehmet dove to depths of more than 130 feet and was appalled with the deterioration of the banks. The sponge diver Mehmet depicts in his stories is a survivor. As he explained, “If you are careful, obey aksona and resist greed, you may dive and be happy all your life.”

The Cradle of Sponge Diving

After my time with Mehmet, I took a boat from the Turkish coast to Kalymnos. I gazed at the seas kept choppy from meltemi, the seasonal wind, as we approached the steep slopes of the barren island. I watched a 24-foot, bidirectional vessel of antique design navigate the waters like a staged show on the prowess of Greek sailors. When we entered the bay with rows of whitewashed houses trimmed in bright Hellenic blue, stepping off the boat seemed like entering a bygone age.

Alexandros Sotiriou, a young diving instructor trainer and social entrepreneur from Athens, awaited us. He spoke fluent English and knew everybody. We met George Roussos, the mayor and a big supporter of diving businesses, commercial and recreational. In its heyday, the community supported an entire school for professional divers run by the Greek navy. Today, there is only one remaining full-time sponge diver, Antonis Komparakis. Roussos located him and helped us to set up the meeting.

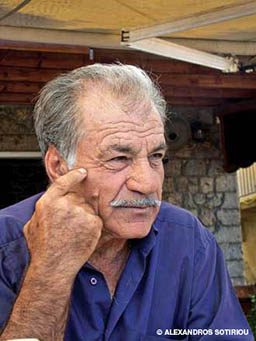

In the best tradition of sponge divers’ hospitality and generosity, Komparakis waited for us at a table set in the best corner of a prestigious local café, with offerings of selected appetizers and raki, the local grape brandy. His appearance belied his 72 years, 50 of which he spent as a sponge diver. He started his career as a breath-hold diver. There were no formal training requirements for breath-hold diving, since all men in the islands did it from early childhood. He dived without hyperventilation and stayed underwater for up to two minutes at a time. His surface interval between dives varied from two to three minutes on shallow dives to 10 minutes for dives to 115 to 145 feet. Hypoxia was known to occur, so each diver had a watcher at the surface ready to help if needed.

Later Komparakis went through the municipality school for compressed air divers; I asked him about decompression, and he acknowledged the importance of adhering to rules. I wondered if he had decompression tables handy on his boat, but he did not. “I read decompression tables while in diving school and memorized what I needed,” he explained. He does not use a dive computer, preferring to stick to familiar dive profiles, unless he has to rush to an important appointment. He has experienced decompression sickness numerous times but nothing severe, as he puts it, although it sounded to me like some of the hits he described may have involved spinal cord injury. As the only provider for his large family, he still dives for sponge regularly. Often he sails out alone, turns on the compressor and dives. So much for adhering to the rules.

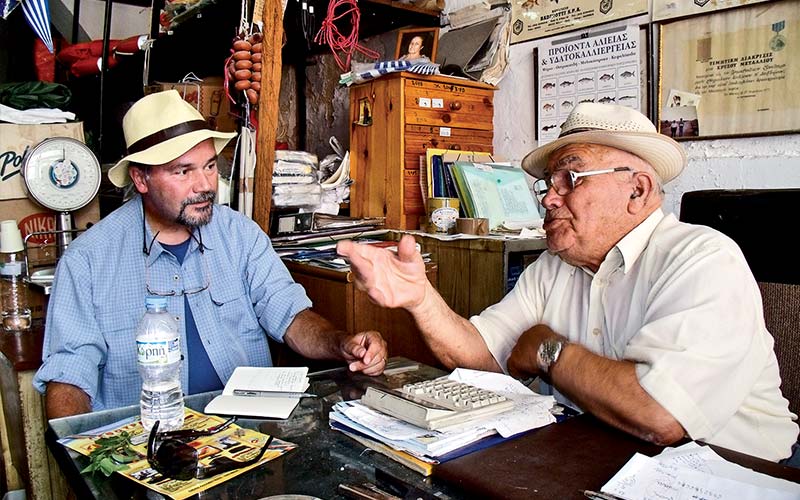

We met Giannis Tsulfas, a 90-year-old former dive boat captain, in the shop he still runs. He became a captain in 1947 and for 37 years ran campaigns along the North Africa coast. Tsulfas told of the lives divers lived in those days; the life was tough both for divers and captains.

Captains borrowed money to finance campaigns and paid divers in advance. If a diver got injured during the campaign, the captain lost money. So captains did their best to keep divers in good shape. Tables prescribed the same decompression for all divers, but captains knew each diver’s abilities and made adjustments accordingly. “Divers with low blood pressure were less prone to decompression sickness than divers with high blood pressure,” Tsulfas came to believe (to date, there is no evidence to support this). Aches and pains were a given, but paralysis was something to fear. Each diver carried a urethral catheter in his sea kit. Captains acted as medics and became skilled in catheterization but used it as a measure of last resort, since divers believed that catheters could hurt their sexual power.

In-water recompression was used extensively, at the discretion of the captain. Some divers healed, others did not. Sometimes divers would be put in a hot bath, improvised using hot water coming out of the engine cooling system. On other occasions, divers would be buried in hot desert sand. It was believed that the injured diver had to stay awake and keep walking throughout the night if he wanted to survive. The recovery rates of such treatments are not known. Tsulfas remembered one of his divers who got paralyzed at the beginning of the campaign. He did not recover completely through in-water recompression and other measures, but he stayed aboard, engaged in daily chores and recovered completely by the end of the season. He lived to be 85. In contrast, another diver who left for home after being paralyzed got worse and died young.

In the End

The history of sponge divers shows us two faces of an empirical approach to life. Thanks to a continuous, centuries-old tradition of occupational breath-hold diving combined with a slowly changing social and natural environment, “naked divers” were able to perform at a level rarely attained by contemporary divers. The techniques they used such as hyperventilation, meditation and work-up dives are still the most effective tools of modern freedivers.

However, when advancement in diving technologies demanded rapid change, the empirical way of learning became insufficient, and sponge divers paid the price. Despite increased scientific and medical knowledge, sponge divers continued to dive riskily and suffered high rates of catastrophic injuries. In a way, their experiences helped advance our knowledge, but they did not benefit from it. Yet, their contributions helped make it possible for all of us to enjoy diving as an exciting and low-risk recreational activity.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2011