IN 2018 AND 2019, MY HUSBAND AND I traveled to 50 locations in 35 countries over 14 continuous months, spending more than 250 hours underwater to research a dive travel guidebook for National Geographic.

Our book, A Diver’s Guide to the World: Remarkable Dive Travel Destinations Above and Beneath the Surface (which will be published in December 2022), is a guidebook for ocean travelers. It’s written for divers who like to travel, travelers interested in the underwater world, and divers traveling with nondiving companions. Each location highlights a global issue — from the necessity of protecting remarkable ecosystems such as coral reefs and mangroves to shark conservation and the importance of the high seas treaty — and suggests ways travelers can learn more and get involved.

It was a diver’s dream assignment, but fieldwork is mentally and physically tough, and this project would require one international flight every week and virtually no time off for 14 months. In the end, we had only six days off during that time.

CARRIE MILLER

Our first call to DAN was during the planning stages. We wanted to know if DAN had recommendations to help us physically prepare ourselves. We would spend a lot of time on boats and underwater, interspersed with long periods of waiting in airports as well as bursts of activity that ranged from studying karate in Okinawa, Japan, to a cross-island trek on Rarotonga in the Cook Islands.

DAN suggested general fitness training, focusing on cardio and balance. In addition, we updated our vaccinations (17 boosters between the two of us), took a first aid course, and prepared a well-stocked medical kit.

Our next pretrip call to DAN was to ask if we should be concerned about nitrogen accumulation with all the flying and diving. DAN assured us that we could keep our risk low by following standard decompression protocols and flying after diving guidelines.

Our DAN membership seemed like an invisible safety net when we finally embarked. It was reassuring to know that a knowledgeable, dive-specific resource was always available to us everywhere we visited. After making hundreds of dives at locations ranging from Easter Island to Greece, we needed to call DAN only twice, and both times were because of Chris. He is an experienced diver whose work in the dive industry has taught him that dive accidents don’t discriminate, so he strives to follow best practices and is eagle-eyed when anything seems amiss.

MAGNUS LARSSON

We made a stop in Hvar, Croatia — a spectacular 42.3-mile (68-kilometer) island surrounded by the glittering, emerald-sapphire Adriatic Sea. A striking fortress with two encircling stone arms dominates the main township. Hvar is known for its enthusiastic dive professionals and good water visibility, with impressive underwater formations and plenty of macro life. Most of the diving tends to be deeper than 66 feet (20 meters).

Chris enjoyed several days of diving around 98 feet (30 meters) without experiencing anything unusual until our last day, which was our planned decompression day. He woke up with an orange-sized swelling on his left elbow and joint pain, with no explanation for either condition.

He called DAN’s nonemergency number, described what was happening, and then spoke to a medical professional. Chris said that he didn’t have any of the usual symptoms of decompression sickness (DCS), but he couldn’t account for the swelling and was concerned enough to seek medical advice. The medical professional spoke extensively with Chris, reviewing his recent dive activity and medical history. Chris has had bursitis, but it’s been rare and always in his knees. Given the lack of any other DCS symptoms but with a desire to rule out anything more serious, Chris was advised to seek medical attention in Croatia. The diagnosis was bursitis, which he’s never had in his elbow before or since then.

A few months later we were on Ko Lanta, an island in the Andaman Sea off the west coast of southern Thailand. The warm, green waters there hold corals in purples and pinks, a wide array of marine life from manta rays to tiger tail seahorses, and many sites to accommodate changing conditions.

Chris isn’t a touchy-feely diver, but he is a magnet for jellyfish stings and, as we found out on this journey, sea urchin spines. Our second call to DAN’s nonemergency number was because of an infected spine in his thumb (he still has no idea how it got there). Once again, DAN advised that we seek local medical attention, and a course of antibiotics cleared up the infection.

CHRIS TAYLOR

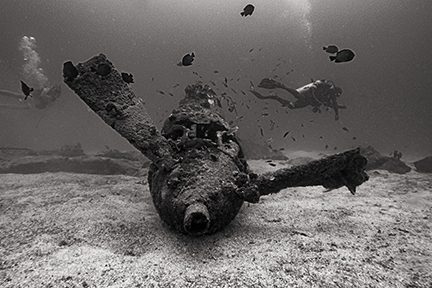

When we embarked on our trip, I was a brand-new diver. I learned the ropes in the most astonishing manner, diving in a new destination almost every week, from exploring the biodiversity-rich gardens of Raja Ampat, Indonesia, to sharing underwater caves with katualis, flat-tailed sea snakes endemic to Niue in the South Pacific.

My learning-to-dive journey was steep, but I felt confident for two reasons. First, I had a dive buddy that didn’t rush or pressure me. There were sites — the World War I wrecks in the Orkney Islands, for example — where I didn’t dive because I felt it was beyond my abilities. I even aborted three dives because I didn’t feel comfortable. Chris always supported my decision and made it clear that it was my choice and responsibility as a diver to dive within my limits. The result was that I felt confident exploring new places and even extending my skill set, flying with manta rays in Komodo’s strong currents and navigating open-ocean dives in 10-foot (3-meter) swells to admire the sharks of Aliwal Shoal off South Africa.

Second, DAN boosted my confidence. As a planner and an overthinker, I believe it’s important to plan for the worst because accidents happen, but having a safety net in place allows us to explore with more peace of mind — and what a world there is to explore! I felt more comfortable knowing that wherever we traveled, in whatever situation we found ourselves, expert, dive-specific advice was a phone call away. AD

© Alert Diver — Q4 2022