As an experienced technical diver I have confidence in my ability to be self-sufficient when faced with unexpected circumstances. But when it comes to decompression sickness (DCS), it’s comforting to know there is an entire organization on standby to care for me anytime.

To look at the kind of diving in which I engage and conclude I’m a daredevil or risk-taker would be a gross misinterpretation of my philosophy regarding the sport. My primary responsibility is to make sure my team and I return safely from every dive. This means I plan for all probable issues and establish contingencies for as many circumstances as possible. I create a dive plan that keeps my team and me within the limits of our experience and training.

As professional divers, we also create a comprehensive emergency action plan for every dive, and a crucial component of that plan is Divers Alert Network®. I consider DAN®, with its extensive resources, one of the most important members of my dive team. Paradoxically, it is also the least expensive. I won’t dive without DAN, and if you want to be on my team, you won’t either. As it turns out, DAN was there for me in three critical instances.

I’ll admit that my first experience with DCS was frightening. I came face to face with all the stigmas and stories that go along with “the bends.” It was September 2004, and I had just completed my expedition trimix training in what can only be called a perfect dive series. Thanks to excellent weather, interesting shipwrecks and flawlessly executed dives, I was ecstatic on my drive home. When I felt aches and pains in all the joints on my left side, I quickly went into a state of denial. It was easy to do — all the dives and decompressions had gone like clockwork, I was in good health, and I’d stayed well hydrated. In short, I’d done everything I was supposed to do to minimize the chances of a decompression incident.

It took me a couple of days to realize I had DCS. Once I did, I called DAN. Talking with the staff was very reassuring. They took a situation that can be scary, even embarrassing, and made me feel as if everything was under control — and DAN did have it all under control. They immediately helped me set up an appointment at the East Texas Medical Center (ETMC) Wound Healing Center. Even better, the hyperbaric physician, Dr. Stephen Rydzak, whom I later chose to be my primary physician, was a technical diver, and chamber technician Matt Unruh was a commercial diver. I could not have been in better hands for my first U.S. Navy Treatment Table 6.

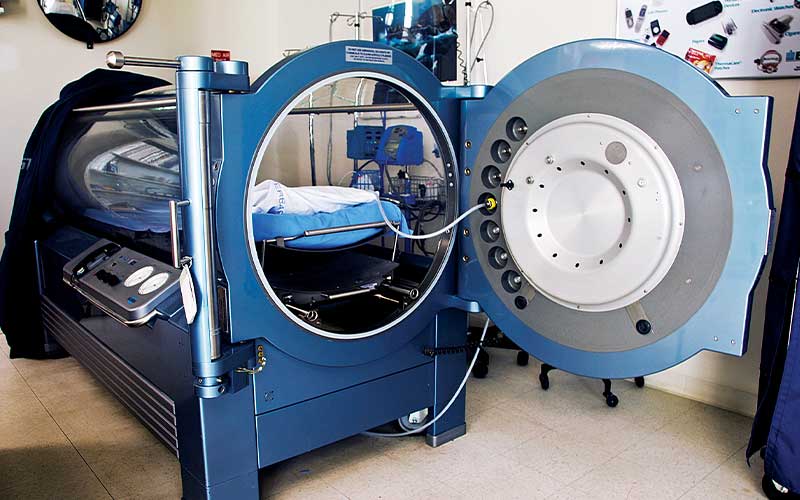

The treatment was easy and nothing like I thought it would be. Through the Plexiglas tube I watched a collection of my favorite dive movies, and everybody at the center was warm and friendly. The pains went away, the treatment was successful, and I was sold — I would never hide or deny symptoms of DCS again.

The next year of diving allowed me to hone my skills and reach new depths. By the summer of 2005 I had completed a diverse assortment of trimix and cave dives. I was doing so much diving that by May 2005 I had already chalked up more than $3,000 in breathing-gas expenses alone.

In June, I headed to Florida with a good friend and dive mentor for a cave-diving trip. It was a fantastic week of outstanding dives, many to depths around 200 feet. We all know it’s unsafe to fly immediately after diving, but this has never been a problem for me; given the amount of gear involved in technical diving, I find it’s easier to drive. The trip home from Florida was a long two days, but my three-quarter-ton Dodge pickup is very comfortable, and I had several audio books I wanted to hear. About halfway through the drive, though, I began to feel a familiar pain in my left elbow. It then expanded into my shoulder, back, hip and knee. A simple self-evaluation was all it took to realize I was probably bent again — no denial this time.

I called Dr. Rydzak; he confirmed that I was likely exhibiting DCS symptoms and told me to call DAN immediately. I wasn’t frightened this time, but I was in total disbelief. How could I be bent? Again, I did nothing wrong on the dives. I was hydrated, hit all my stops and analyzed my gases. What could have happened?

The medic at DAN recommended prompt evaluation by a doctor. At this point in my drive, the closest medical facility was ahead of me at ETMC in my hometown of Tyler, Texas. It was after-hours when I arrived, but both Dr. Rydzak and Matt were waiting at the door for me. Dr. Rydzak examined me and prescribed a Table 6 hyperbaric treatment. Once at depth in the monoplace chamber, my symptoms began to dissipate.

Twice now, DAN had been instrumental in aiding my healing and providing answers to my questions, even those that seemed insignificant. Thanks to the quick and complete resolution of my symptoms, I was able to continue with the dive plans I had for the year — always cautiously monitoring my body for any signs or symptoms of DCS.

In September 2005, my schedule had me off Florida’s east coast on some deep-wreck work-up dives. By now, I was analyzing every aspect of my diving to thoroughly minimize my chances of DCS. For instance, I made changes to my postdive routine. As is recommended with air travel, I didn’t embark on long drives for at least 24 hours after deep dives. “Plan your drive, and drive your plan” became my new mantra, and so far it seemed to be working.

I got home from the wreck-diving trip suffering no ill effects and immediately began packing my suitcase for a fun trip to Colorado. I planned to fly to New Mexico and drive through Santa Fe up into the southern Colorado mountains. This route delighted me enormously because of the dramatic mountain scenery and the incredibly spicy food. As I approached the highest mountain pass of the route I began to experience blurred vision and other strange symptoms. Surely this wasn’t DCS again. I was at a complete loss to explain what was happening to me. To make things worse, I had no cell signal, so I had to wait until I made it down from the pass to call Dr. Rydzak and DAN. When I did, both advised me to seek immediate medical attention. The nearest hospital was behind me, but I had no intention of turning back to go over the pass again. I decided to push on to my destination, Pagosa Springs, Colo.

I made it to Pagosa Springs, where the local physician was unable to rule out DCS and advised me to seek hyperbaric chamber therapy. The nearest chamber was a five-hour drive away and, to make matters worse, over passes that would put me 8,000 feet above sea level. DAN sprang into action. They arranged for an ambulance transfer to the Durango airport and a pressurized chartered jet to hustle me down to Albuquerque, N.M. In less than two hours, I was in a chamber for my third hyperbaric treatment. Thankfully, my symptoms began to subside as I began breathing oxygen in the ambulance, and they fully dissipated as I was pressurized to 60 feet in the monoplace chamber.

After one day of treatment and two days of observation, I returned to Pagosa Springs to finish my trip, but nothing about my life went back to normal. With repeated unexplained DCS hits, I was searching for answers. I read extensively on dive physiology and decompression theory to learn everything I could. I underwent tests to try to determine whether I had any medical conditions that would increase my risk. The results left me with mixed emotions. I did not have an atrial septal defect, which was a good thing, but the negative test results brought me no closer to understanding why I had been bent three times. Perhaps it was time for me to choose a new career?

For the time being, I halted my deep diving and carefully analyzed my profiles and dive behaviors. After hours of phone consultations with DAN and weeks of scrutinizing my diving habits, I came to a conclusion. I’m certainly not an authority on the subject, but I now realize that each decompression injury is based on a whole host of shifting variables, many of which can be mitigated — but only to a degree that is relative to each individual diver. In other words, methods that help lower the chances of DCS for one diver may not work for the next diver.

Since incorporating some additional adjustments to my breathing-gas mixes, my decompression schedules and my gas switches, I have dived without incident. I still dive deep while taking every precaution. Knowing I have the entire DAN organization of researchers, medical professionals and divers looking out for me is an enormous source of comfort and allows me to fully enjoy my time in the water.

The Medic’s Perspective

Ulloa summarizes nicely the way many factors might contribute to an individual’s risk of decompression sickness. We humans tend to find DCS extremely frustrating because there are seldom obvious causes beyond depth and bottom time. We know these are the two most important elements of DCS risk, but according to DAN medical department estimates, more than 90 percent of cases occur in people who are reportedly diving within the limits of their computers or dive tables. Therefore, other more subtle factors may be involved. Hydration, nutrition and fatigue are probably relevant, but their importance is often greatly overstated. Even anatomical variations like patent foramen ovale (PFO) are not necessarily associated with quantifiable changes in divers’ risk of DCS.

Ulloa’s story shows how sometimes carefully devised dive plans and closely followed decompression schedules are not enough to prevent DCS. In his case, he was forced to discover and implement modifications to his dive planning to keep his risk at an acceptable level. His resolution to never again deny symptoms after his first brush with DCS might have saved him from more persistent symptoms following his subsequent experiences. His decision to avoid long road trips immediately following deep dives was a sensible one — managing DCS is stressful enough without the added challenges of operating a vehicle in an unfamiliar and perhaps remote location. A return to diving after multiple cases of DCS is not always possible, but thanks to prompt treatment and complete recovery in each of his cases, as well as the time and effort he spent researching his problem with the guidance of his physician and DAN, Ulloa has been able to continue to make his living diving.

— Brian Harper, Alert Diver medical editor

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2011