My heart raced with excitement as I swam slowly toward two giants resting at the surface. I felt overwhelmed with joy because I was about to meet a mother humpback whale and her young calf.

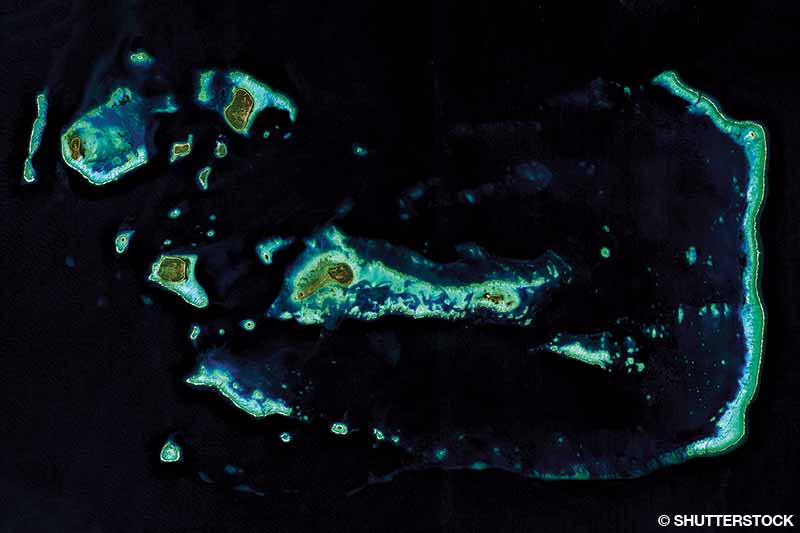

I had traveled to the Kingdom of Tonga, a South Pacific archipelago between New Zealand and Samoa. A strong culture, an unspoiled landscape, deserted sandy beaches, spectacular limestone cliffs, underwater caves and lush forests are among the many reasons to visit Tonga. Its main tourism draw, however, is the possibility of swimming with charismatic humpback whales.

Among the largest animals on the planet, humpback whales measure about 49 feet (15 meters) long and weigh about 35 tons on average. The humps near the front of their dorsal fins, the distinctive knobbly protuberances on their heads, and their beautifully long pectoral fins make them easy to identify. The fins, combined with the area in which scientists first described them, earned them their scientific name, Megaptera novaeangliae, meaning “large- or great-winged New Englander.”

Humpbacks feed in polar waters during the summer and then migrate to tropical or subtropical waters to breed during winter. Various locations offer seasonal whale-watching, but swimming with them is legal in only a few places — Tonga is one of them. Every year its warm and sheltered waters provide a nursery for the whales, which gather there between July and October after a long migration from Antarctica.

Tonga was not always a safe place for humpbacks. Whalers hunted them there for decades until 1978, when King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV declared a moratorium on all whaling within the kingdom’s waters — a decision that probably saved the Tonga humpback subpopulation. The government issued the first tourism license for whale swimming in 1993, and since then thousands of people have traveled there from all over the world hoping for the experience of a lifetime with the majestic giants.

Swimming with whales has strict guidelines, and only licensed operators can offer in-water activities. Key regulations include that only four clients and one trained local guide per certified boat may be in the water with any single pod of whales at a time and swimmers cannot approach any whale closer than 16.4 feet (5 meters).

Only one licensed vessel at a time may put swimmers in the water with any single pod of whales. Some operators might agree to share so that all clients have a chance to experience an in-water encounter. The maximum interaction time of any vessel with any individual pod of whales that includes a mother and a calf is one and a half hours unless they have a Special Interaction Permit. After any 90-minute interaction, no boat may attempt to interact with the pod for another 90 minutes, ensuring that the animals get a break.

I have been fortunate to travel to Tonga many times since 2007. People often ask me why I keep going back, but there aren’t adequate words to convey what it is like to be in the water with humpback whales. Swimming with them was truly life-changing. It gave me a sense of peace that I had never experienced, and it humbled me that the gentle giants would be so tolerant of us. After hundreds of swims, I still feel overwhelmed each time and remain amazed by their size, inquisitive nature and level of consciousness.

I’ve also observed the powerful impact the whales have on other people. I have seen individuals weep with joy. Some go quiet for hours, deeply touched by the encounter, while others get so excited that they won’t stop talking about it.

Over the years I have been privileged to observe amazing interactions that will forever remain imprinted on my memory. One of those unforgettable encounters was with a calf we named Snowy because of his pale skin. He was curious and determined to play with us slow, tiny humans. We had spotted the mother and calf pair from quite a distance as they were breaching. The mother effortlessly and gracefully leaped out of the water, but her calf was not so elegant and still in training. His clumsy and uncoordinated attempts to breach were a delight to watch.

After they stopped and seemed to settle, we quietly entered the water and started swimming slowly toward them. The calf left his mother and came charging at us as soon as he saw us in the water. Remember, this is not a small baby — it’s about 15 feet (4.6 meters) long and weighs more than a ton. Having a humpback calf chase you can be intimidating, especially since they tend to lack spatial awareness.

Our time in the water was magical and exhilarating, as Snowy kept circling us, rolling and swimming on his back while always maintaining eye contact. I spent most of the swim laughing as I tried to capture pictures of this playful little one. My wide-angle lens was not wide enough to accommodate such a close encounter, so I could often photograph only part of him.

Humpback mothers can be very protective of their calves and usually stay quite close, so I kept an eye on her while interacting with her calf. Surprisingly, this mother rested motionless below us for most of the swim. I suspect her trust resulted from previous respectful approaches by people, or perhaps she was enjoying time off while we kept her boisterous calf occupied.

Another exceptional experience was with five adult whales engaging in a slow-motion heat run. Heat runs can be aggressive, as several males race and compete for the attention of a female. Operators need to carefully assess heat runs before allowing swimmers in the water. If safe drops are possible, they usually last only a few seconds as the animals swim past. But that day was quite different — the whales were swimming relatively slowly compared to usual and at times would change direction and come back toward us. It felt like I was training for the Olympics, but we never managed to get closer than about 30 feet (9 meters) during the hour we spent with them.

It was extraordinary to watch their behavior underwater. Initially, the males were mainly chasing after the female. They would speed up, cut in front of each other and blow curtains of bubbles, possibly to confuse their opponents and hide as they tried to escape with the female. The competition escalated quickly, however, as power and chaos replaced speed and deception. It became a battle of titans in which the males displayed their strength by headbutting and tail-slapping each other. One slap was powerful enough to resonate to where we were. The recipient was swimming on his side, and we saw his throat grooves shake when the other whale struck him. I felt the impact’s vibrations in the water. The whale that had just been hit continued racing as if nothing had happened, driven by the urge to reproduce.

All the whales suddenly dived in unison and disappeared for several minutes. I don’t know what happened in the deep blue, but it ended the chase. When the whales eventually reappeared more than 300 feet (91 meters) away, their pace had slowed significantly, and the group quickly separated afterward except for two whales that swam away together — probably the female and her chosen suitor.

Swimming during a whale song is also fascinating. It is difficult to describe the mix of varied high-pitched moaning and grunting sounds that humpbacks produce. Only hearing and feeling the song underwater does full justice to its mesmerizing and haunting beauty. It is a long vocalization, among the most complex in the animal kingdom, and produced in organized patterns only by males. They may sing for several hours at a time, repeating the same song over and over.

Because whales usually sing most often during the breeding season, researchers believe the complex songs play a role in attracting females or establishing dominance between males. We are still attempting to understand whales’ singing during other times. All the males in a humpback population will sing the same song; if the song changes over time, they all will apply the same changes — proof that learning and transmission are happening among the males. Apart from being music to your ears, whale songs can be quite a physical experience. When positioned near a singer, you can feel the vibrations in your body.

My all-time highlight was a swim with two courting whales 10 years ago. That day our swim attempts had been unsuccessful — we had seen many whales, but none of them seemed interested. On the way back to the harbor, however, we suddenly saw big splashes in the distance as two adults rolled at the surface and slapped their long pectoral fins. I prefer to observe whales underwater, but watching them from a boat always gives a different perspective of size and sound. We could hear them breathe, and the rhythmic sound of their fins splashing the water was captivating.

They eventually stopped to dive, so we entered the water and swam toward where we last saw them. The pair was there, gliding slowly underneath us and pirouetting around each other, meeting and separating as if performing an underwater ballet. I am always amazed by humpbacks’ gentle and precise movements despite their size. One of the whales suddenly ascended straight in front of me less than 10 feet (3 meters) away and stopped there, clearly looking at me. The overwhelming feeling when looking into a whale’s eye and knowing that it is looking back and acknowledging you is unrivaled. It’s a moment in time that will remain vivid in my mind forever.

I have many other treasured memories, and I am lucky that my trips to Tonga have been rich with unforgettable interactions. It is essential, however, to appreciate that swimming with whales is a privilege. It requires patience and luck, and as with any wildlife experience, there is no guarantee that an interaction will happen. Some days the weather is too rough for us to get out on the boat, and some days the whales are not willing to allow us in the water with them. On most days you will spend hours looking for them.

Remember that the whales travel to Tonga to mate, give birth and care for their calves. The migration is more than 3,700 miles (5,955 kilometers) and takes several months. While migrating and staying in the birthing grounds, there is little or no available food, so whales survive by metabolizing the stored energy in their blubber. Mothers can lose up to one-third of their body weight during the migration and their stay in Tonga. It’s demanding and exhausting to protect, nurture and feed their babies in preparation for their long trip back to Antarctica.

The Tonga humpback population is still relatively small and has not recovered as fully as other humpback populations. Estimates are that whalers killed more than 200,000 humpbacks in the Southern Hemisphere in the 20th century. Antarctic whaling reduced breeding stocks E and F, the subpopulations that breed in Tonga, New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa and Niue, and the population is now in the low thousands.

While you are in the water with humpback whales, it is vital that you are respectful and do not affect their behavior and well-being. Doing so will ensure that you and other visitors have an experience like no other.

How to Dive It

Getting there: Tonga’s borders closed quickly after the pandemic started, so check travel advisories for the current status. Before COVID-19, you could get to Tonga via Sydney, Auckland or Fiji. From the U.S., flights leave from Los Angeles and connect through Fiji. Most international flights arrive at Fua‘amotu International Airport, Tongatapu, but a few direct flights happen weekly between Fiji and Vava‘u. If your whale-swimming adventure takes place in Vava‘u, Ha‘apai or ‘Eua, you can take a domestic flight on Lulutai Airlines.

Allow plenty of time between your domestic flight’s arrival time and your international flight’s departure for your return trip. Domestic flights occasionally get delayed or canceled due to weather, causing missed international connections.

I recommend carrying all your essentials with you, including your camera housing. Luggage delays due to being over the weight limit are not uncommon. It’s also good to have travel insurance to cover medical expenses, repatriation, flight delays and cancellations, and lost luggage.

Where to stay: Tonga is home to about 170 islands divided into three major groups: Tongatapu and ‘Eua in the south, Ha‘apai in the middle and Vava‘u in the north. The northernmost tip is the small Niua island group. Tourism infrastructure and whale-swimming conditions vary depending on the location. Staying on the main island, Tongatapu, for your whale experience will save you time and money because you won’t have to take a domestic flight to another destination, and far fewer operators are on the water. Your best option for hotels and activities is in the capital, Nuku‘alofa.

Most travelers prefer to take the one-hour flight to popular Vava‘u, the hub for whale swimming. Vava‘u is a scenic location with deeper waters and the possibility of seeing other pelagic species. The influx of tourists during the whale season has resulted in a wide choice of restaurants and accommodations to fit all budgets. The main town of Neiafu is a popular option, but quieter, more secluded resorts are located on the outer islands. The downside is there are many whale-swimming boats, increasing pressure on the whales. In the past few years, queueing for a whale has become more common.

There are fewer boats in Ha‘apai, where the tourism infrastructure is less developed than in Vava‘u. The waters are shallower, and the visibility is usually not as good. It is also flatter and more exposed to the weather. The most accessible islands in Ha‘apai are Lifuka, Foa and Uoleva.

When to go: The whales arrive in Tonga in mid to late June, and you can typically observe them until early October. The timing varies, so August and September are usually more reliable for whale encounters. These winter months can have strong winds, so have warm clothes and a spray jacket on the boat. Water temperature in August and September is usually in the mid-70°F (low-20°C) range.

It is essential to book your whale-swimming tours with licensed operators. Their crews are trained on regulations and best practices to use when approaching the whales, and their boat and safety equipment are suitable.

Booking for several days will maximize your chances of good swims and opportunities to see different behaviors. Three days is a good minimum, but five or seven days will be better if your budget allows. There is no guarantee you will swim with whales, and any operator who tells you otherwise may not follow ethical practices. Allow a few extra days at the end of your trip in case your allocated whale-swimming days are postponed due to weather or

other reasons.

Only four people and a guide are allowed in the water with the whales at any given time, so joining a small group will limit the rotations and maximize your time in the water. It is a snorkeling experience; scuba equipment and strobes are not allowed.

Note to photographers: Tonga is remote and doesn’t have a photography shop or support. Make sure your equipment is in perfect working order before going to Tonga. If you stay on an outer island, charging equipment might be available only at certain times of the day, so be sure to have spare batteries and memory cards in case you cannot charge or download daily. Drones are allowed, but talk to a licensed operator at the time of booking to determine the current permit requirements.

Explore More

See more of Tonga’s humpbacks in this video by Annie Crawley.

© Alert Diver — Q3/Q4 2021