In 2010, DAN employees Eric Douglas and Matias Nochetto, M.D., traveled to La Ceiba, Honduras, to conduct a safety assessment of the hyperbaric chamber at a local clinic. Their trip was a part of DAN’s Recompression Chamber Assistance Program (RCAP), a means for providing technical support, education and equipment for chambers in remote locations. During that trip they witnessed five cases of severe decompression illness (DCI) in only three days.

As a result of their visit to La Ceiba, in the Miskito Coast region of Honduras, Douglas and Nochetto created the Harvesting Divers Project, an initiative designed to reduce the incidence of DCI and improve its outcomes among divers who fish for lobster and other marine commodities. Through his work with that project, Dr. Nochetto realized DAN had an opportunity to help not only the harvesting divers but also the hyperbaric medicine community worldwide. There in La Ceiba was a tragic laboratory, an opportunity for physicians and other medical professionals to be exposed to more — and more severe — cases of decompression sickness (DCS) than most hyperbaric doctors see in their lifetimes.

So in 2012 Nochetto started the DAN Emergency Dive Medicine Rotation, through which doctors would visit Clinica La Bendición and gain invaluable experience treating injured divers. To date, the program’s participants have been Marcelo Tam, RN, of Brazil; Evan Kornacki, EMT, CHT, of Texas; and Helena Horak, M.D., of California. The following is Dr. Horak’s account of her time at the clinic.

Out of 11 divers, two were dead and six were paralyzed. These were the patients Elmer Mejía, M.D., saw in a two-week period at Clinica La Bendición in La Ceiba, Honduras. As an emergency physician in the last year of my training, I traveled nearly 2,000 miles to see patients with severe DCS, an emergency that occurs only rarely in the United States. Although I ultimately learned how to treat DCS, I also gained an appreciation for the complex challenges the Miskito fisherman divers face and the tenuous financial condition of the medical clinic that provides their care.

As a recreational diver, I love Honduran waters. Roatan and Utila, the best-known dive spots, attract thousands of visitors each year. With visibility that exceeds 100 feet, enchanting coral formations and prodigious schools of fish, these waters are mesmerizing. In Roatan I saw a spiny lobster fearlessly waggling his antennae — he was untouchable in the protected marine reserve. His less-fortunate relatives farther out in the ocean are the targets of the lobster industry.

The lobster boats that supply the seafood industry in the United States rely on the work of Miskito Indians, natives of the Caribbean coasts of Honduras and Nicaragua. The profiles of these divers are superhuman: Each one routinely dives to 90-130 feet as many as 12-16 times a day to catch lobster. Often they are on the surface for only minutes between dives, and they rarely if ever conduct decompression stops. The boat owners provide only rudimentary equipment: a cylinder, a regulator, a mask and fins. A length of rope serves in place of a BCD. There are no depth gauges or wetsuits, and dive computers are unheard-of luxuries. As a consequence of the risks they take, the incidence of DCS among the Miskito Indian divers is unprecedented.

Clinica La Bendición is a small refuge for injured Miskito Indian divers as well as the residents of La Ceiba; its name means “the blessing” in Spanish. The clinic was founded by Dr. Elmer Mejía, who originally learned dive medicine while working as a medic in the Honduran navy, operating the hyperbaric chamber in Roatan through the Episcopal Church. When the chamber closed, Mejía went to medical school in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, but his heart was with the divers. A different hyperbaric chamber was donated to his clinic, and he drove a truck with the chamber from Virginia to Honduras. The clinic is a family operation: Mejía’s wife is a nurse there, and his brother runs the chamber and sleeps at the clinic as improvised nighttime security.

My first patient in the clinic was Oscar. Five feet tall with a thin frame, he was 33 years old and had been diving for eight years. With boundless energy, he gregariously chatted about his two children, who were three and five. Oscar was harvesting lobster to make some extra money for their education. The divers earn $2.50 per pound of lobster, and a productive two weeks can mean up to $200, a windfall in an area where per-capita annual income is US $1,600.

Oscar was on his sixth tank of the day when the mermaid struck. Dreaming of the mermaid is dangerous in local lore — the siren catches the diver and keeps him in the deep. The DCS manifested as searing pain down his left leg, then complete paralysis. The other divers tried to relieve his pain, taking him back underwater with two tanks of air to try to recompress him, but he still couldn’t move his legs. Oxygen, the mainstay of treating DCS, is never available on the boats. We gently cradled Oscar into the chamber and began the treatment.

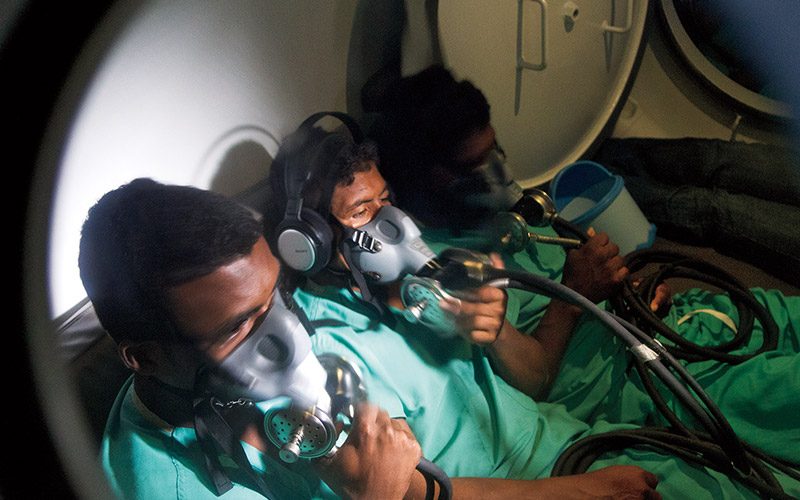

I joined Oscar in the hyperbaric chamber. Equalizing my ears as the chamber pressurized, the temperature gradually rose to sauna levels. Because of the fire risk, no electronics are allowed in the claustrophobia-inducing chamber, and permission to read books means little to the illiterate divers. Although up to five people can fit in the main chamber, the sucking masks of hyperbaric oxygen tightly affixed to the patients’ faces stymied my attempts at conversation. The treatment, a U.S. Navy Treatment Table 6, lasts nearly five hours. But Oscar is used to waiting — he arrived five days after his injury because the lobster boat needed to complete its fishing trip; medical care for an injured diver was not the priority.

The next divers I met, three men in their 30s to early 50s, were lucky to arrive within two days of their injuries. A fourth diver was pulled convulsing from the water, paralyzed and soon comatose; he died a day later. The fishing expedition was terminated early so he could be buried. Thus far, there had been 15 deaths this season. This was the fourth death for the same boat owner in the four months of the season so far, and the worst months, November and December, still had not started. Mejía commented that divers are injured on some captains’ boats regularly, “[they have] little graveyards to their names,” while other captains rarely have injured divers.

Being wheelchair-dependent is a death sentence for the divers. After they become dependent on a foley catheter to urinate, divers will live an average of two years, generally succumbing to pressure sores and urinary tract infections. They also present an economic burden on their families and communities, depending on others to provide for their basic needs.

The dive-boat owners are supposed to be responsible for the divers’ illnesses. For each U.S. Navy Treatment Table 5 (a shorter chamber visit commonly used for follow-up treatment), the patient needs one or two tanks of oxygen. Each oxygen tank refill costs $28, roughly a week’s wage for an average worker. This represents the cost of the oxygen only, and the expenses quickly escalate depending on the length of the treatment. For every 10 divers the clinic treats, it gets paid for only three. Boat owners commonly drop off the patient and then refuse to answer their phone. The clinic is stuck with the cost of medical care and oxygen and sometimes pays for the patient’s food and transportation back to La Moskitia.

The three divers recovered quickly, leaving after two treatments, but Oscar’s recovery is more measured. Every day after his hyperbaric treatment he’s on the stationary bicycle; he frequently paces the clinic grounds, willing his leg to get better. He talks about the dangers the divers face underwater such as barracudas, sharks and other more mythical creatures. The fish that captures my imagination is known locally as the pega pega. This fish is territorial and has the strange tendency to strategically strike at men’s nipples. According to local lore, if a diver encounters this fish, his wife is unfaithful. Furthermore, the meat of the fish can be a powerful aphrodisiac. Adamantly denying using the fish for romantic prowess, he teases, “I’d have more children if I used it.”

Mejía has been pushing the limits and knowledge of hyperbaric medicine. Conventional wisdom holds that hyperbaric treatment is no longer useful more than two weeks after an injury. Even if a patient has been afflicted by his injuries for a prolonged period, Mejía tries hyperbaric treatment; the longest delay after which a patient still experienced some improvement was 105 days following the injury. Mejía also routinely gives patients chamber treatments up to five or six times if they do not improve, while many hyperbaric doctors stop after one treatment if there is no improvement. Generally, after the first treatment, the physician has an idea of how quickly the patient will improve.

To recover strength in his leg, Oscar required eight treatments, which is unconventionally long. He gingerly jogged around the clinic in restless impatience — he had not left the clinic grounds for nine days. Security plagues the clinic as it does the country, and walking around the clinic can be unsafe at any time of day. A hired guard with a shotgun supervises the clinic entrance after an armed intruder emptied the clinic cash register at gunpoint. Kidnappings have been an increasing problem, and a local teenage girl was taken for ransom during my stay. Now that the wealthy have employed increased security, the kidnappers have shifted their focus to middle-class people or the poor who have the means to borrow money to pay a ransom.

Before Oscar finally left the clinic, he promised us he would cease diving. If he gets sick again, he probably won’t recover. Mejía has seen this before: The divers who have slow recoveries are more likely to succumb to DCS; if they do, they often do not recover motor function. “He’ll be back,” Mejía sighed. “Even divers on the brink of death have returned to diving.”

Job options on the Miskito Coast are severely limited outside of diving and drug trafficking. Some advocates push for bans on the local diving industry but provide no economic alternatives. Mejía is pushing for additional regulations and safeguards to protect the divers such as better diving equipment and oxygen tanks for patients to breathe until they can reach the chamber.

Mejía’s goal for his clinic is to make it self-sustaining, but its future is uncertain. He has appealed to the Honduran government for financial help for the clinic; the government has expressed intermittent willingness to provide financial support, but it has difficulty maintaining basic public services. During my stay, the government had not paid its national hospital employees for six months, and all services except emergency care had ceased due to a strike. The clinic spends more than $3,000 a month in oxygen alone. It continues to run because Mejía covers many of the costs himself, and his staff is willing to accept a low salary for the sake of the vulnerable community they serve.

On my final day in Honduras, I took one last dive in the crystalline Caribbean waters and again spied a spiny lobster on the reef. Its species is responsible for an entire industry and the livelihoods of many of the people I met. Because Americans crave lobster, Oscar may be able to send his children to school in hopes of a better future.

By being responsible consumers, we could help make harvesting lobster a safer job for the Miskito divers. Americans developed a modestly successful campaign to buy dolphin-friendly tuna, and similarly we could demand that our lobster doesn’t come at such a terrible cost to other people. Small improvements in equipment and oversight could significantly reduce the hazards these divers face.

I took my final breaths underwater and watched my bubbles stream upward. If I surfaced too quickly, bubbles could cause problems for me. But I knew I had access to a chamber and, ultimately, medical care in the United States should I need it. Miskito divers do not have such certainty. As I left the water, I contrasted my pleasure with the somber experience of the Miskito divers who face death with every dive. Mejía and Clinica La Bendición are more than a blessing for the Miskito divers: They’re a second chance at life.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2014