As you would expect of a scuba enthusiast, my primary motivation for traveling to Australia over the past decades has been the attractions below the surface. But I’ve learned that Cairns and Tropical Queensland are quite special topside as well. In fact, as a resident of a dive town myself (Key Largo, Fla.), I’ve always felt Cairns may be the planet’s perfect dive portal.

First, it’s relatively easy to get to. It involves a fair bit of time on an airplane from anywhere in North America, of course, but compared to other Coral Triangle destinations that require similarly long flights just to get to gateway hubs in Bali or Singapore and three more regional hops thereafter, travel to Cairns feels very civilized. Most itineraries require a connection in Sydney, Melbourne or Brisbane, but at 21 hours from the Los Angeles airport, Cairns qualifies as one of the most accessible “exotic” destinations for North Americans.

Topside Cairns

Once there you’ll find a vibrant and cosmopolitan city of more than 150,000 with most hotels, restaurants and tour operators located around the seafront and the famed esplanade. The diverse tour options include day trips to nearby reefs for diving or snorkeling, but be aware that Cairns’ near-shore waters are fairly murky due to runoff from the area’s rivers.

For North Americans who travel that far specifically for the diving, day trips cannot deliver the quality available farther afield. To sample the best requires the extended range of a liveaboard dive boat. World-class liveaboard tours such as those offered by Spirit of Freedom, Mike Ball Expeditions and ProDive provide three-, four- and seven-day itineraries out of Cairns in addition to less-frequently scheduled 11-day trips to the Far Northern Great Barrier Reef, Coral Sea and Great Detached Reef. More about these options later, but at the beginning or end of such a trip, the Cairns region is compelling enough that a few days of exploration should be scheduled.

I’ve never tried the whitewater rafting, which is rumored to be exceptional, but I have enjoyed many tours of the nearby Daintree Rainforest National Park. You can easily take a train into the forest, do a walkabout and, at your leisure, hop on the Skyrail Rainforest Cableway to get back to town. Check out the Cairns Tropical Zoo to get a sense of the local wildlife, which includes huge saltwater crocodiles and, of course, highly photogenic koalas and kangaroos. While not cheap, aerial photography tours of the Great Barrier Reef via helicopter make for valued additions to a Cairns image portfolio.

The excursion I enjoyed most was a hot-air balloon ride over the nearby countryside, even if it did involve a decidedly uncivilized 4:30 a.m. pickup from the hotel. Arriving before sunrise allowed us to see the balloons in the dark, transilluminated by the inflation flames. Having been thoroughly briefed by the DVD on the bus ride to the launch site, we climbed into our gondola, and four balloons lifted off nearly simultaneously. Ballooning is a very quiet means of aviation, except when the fuel jets are running.

While the equipment was all very safe and high tech, there was something timeless about drifting wherever the wind took us; the only means of control was altitude adjustment, which allowed us to take advantage of varying prevailing winds. We had a 30-minute balloon ride, which seemed long enough, and after a hot breakfast complete with champagne, we were back at the hotel by 10 a.m.

Potato Cods and More

Years ago I was on a white shark expedition in South Australia with legendary Australian photo team Ron and Valerie Taylor. I recall Valerie reminiscing about how she and Ron were champion spearfishers at one point in their lives, but they were never blind to the beauty of marine life, which made their transition to filmmaking a natural one. They were appalled to see Australia’s friendly potato cod being speared nearly to the point of extinction, so Valerie launched a campaign to save the species, finally convincing the government to protect it. Now the Cod Hole, at Ribbon Reef No. 10, is one of the most famous dives in Queensland and a tribute to conservation.

The Cod Hole is a lovely coral amphitheater in 20 to 60 feet of water with delicate staghorn and antler corals as well as massive boulder corals. The marine life is impressive, with schools of bannerfish, surgeonfish and several species of grouper in residence. But without a doubt, the stars of the show are the potato cod. They are clearly conditioned to being fed and appeared directly under the boat as we jumped in. We easily achieved fish portraits and even close-focus, wide-angle shots of these groupers against pristine boulder-coral backgrounds. The marine life was very approachable here, as the area is totally protected, with no spearfishing or hook-and-line angling allowed.

As the ambient light dimmed toward the end of the day, I used a 100mm macro lens and found the site extraordinarily productive for reef minutia as well. There were plenty of small butterflyfish flitting among the hard corals, and I could now get tight shots of cleaner wrasse at work. I watched with interest as a large bumphead wrasse munched away at the reef with a seemingly insatiable appetite.

Thanks to enlightened management, the Cod Hole was actually a much better dive than the first time I visited it, but some of the other sites of my first-ever dives on the Great Barrier Reef showed signs of stress. Years ago I did a commercial shoot for Alcan Aluminum at Pixie Pinnacle. Alcan manufactured the aluminum used in scuba tanks, and they wanted a shot of a diver wearing one. Of course, we could have done that anywhere, but the ad campaign used the tagline “Down Under Down Under,” so we hopped a plane and a liveaboard. Along with a team from the ad agency (including a creative director who didn’t even dive), my wife and I dived Pixie Pinnacle and got the shot against a backdrop of lavish soft corals and colorful gorgonians.

Unfortunately, pinnacles are vulnerable to diver impact. It’s not a matter of direct contact so much as exhaust-bubble percolation. Divers circle the relatively small spire nearly constantly, and the steady stream of exhaust bubbles inevitably takes a toll on the filter feeders that decorate the shallow portions of the bommie. Of course, my comparison of the site to its previous state is based on recollections from more than two decades ago, and significant changes over that many years are not unexpected.

It wasn’t long before I began to see beyond what was missing to what was there. Clouds of anthias flitted above hard corals, many of which were remarkably pristine. The groupers were far more bold and approachable here than in many other areas of the world, which is another testament to intelligent conservation. Pixie provided multiple encounters with lionfish, both common and fire, as well as Moorish idols, various species of butterflyfish, weedy scorpionfish and stonefish. Finding a wobbegong on the night dive added to what was an incredibly productive series of dives. Even after many years, the opportunities for marine-life photography I found at Pixie Pinnacle were exhilarating.

The 55-mile chain of islands known as the Ribbon Reefs is probably the best spot along the whole Great Barrier Reef to experience the biodiversity of 1,500 species of fish and 400 of coral. This is thanks to the area’s nutrient-rich currents, which flow between the reef structures and nourish a remarkable array of creatures including pygmy seahorses, manta rays and whales. While there may be better places in the Indo-Pacific region for macro photography and better places for wide-angle, the sheer diversity of medium to large tropical reef animals and their willingness to be approached by scuba divers because of a legacy of marine conservation make the Ribbon Reefs hard to beat.

The next day found us exploring Challenger Bay, where pristine hard corals rise from depths of 30 feet almost to the surface. A massive school of trevally jack greeted us just beneath the swim platform, while a small school of chevron barracuda worked the edge of the reefline. Within the vast expanse of bay are several small bommies, which rise nearly 50 feet from a 70-foot bottom. Masses of opal sweepers and bannerfish decorated the wide view, while the macro enthusiasts came back to the boat with captures of leaf scorpionfish, spinecheek anemonefish and longsnout butterflyfish.

The next stop was Lighthouse Bommie, a solitary pinnacle rising from 85 feet below to within a few feet of the surface. Huge schools of goatfish and bluelined snappers reside at the base of the pinnacle, and amid the tubastrea-encrusted overhangs we found a sleeping green sea turtle. Returning for an incredible night dive, we spotted five more turtles likewise tucked in for the night. It’s a big ocean out there, and protected spots in which to nap are apparently hard to come by.

In June and July, Lighthouse Bommie is a good place to encounter minke whales. Because they usually leave if they’re chased, the protocol is to snorkel as a group while connected to a floating line. The whales are curious and tend to come close quite often, which makes minke encounters reliably engaging during the season.

The Coral Sea

While the Great Barrier Reef is notable for its rich marine life, particularly along the Ribbon Reefs, a 75-mile overnight steam allows divers to awaken to the vast crystalline wilderness of the Coral Sea.

At Osprey Reef the stunning water clarity can be appreciated during a high-voltage shark feed at North Horn. The briefing leads us to expect 30 to 50 sharks, mostly gray reefs with the possibility of some silvertips and even a great hammerhead.

The wall slopes precipitously here, and there are lovely soft corals around 80 feet and deeper. We saw several potato cod at North Horn, but the greater attraction here were the whitetip reef sharks lying about on the bottom. Of course we had seen them on many other dives, but they were more approachable here, and this reef offered better backgrounds. Soon the gray reef sharks began to arrive — clearly attuned to the presence of a dive boat. On our second dive at North Horn the crew roped down a garbage can full of fish heads strung along a stainless-steel cable. When the divemaster lifted the lid the sharks charged, more than 40 of them gnashing and ripping into the bait, while various grouper and snapper patrolled the seafloor eager for the bounty of detritus raining down from above.

Significantly, the Coral Sea now has even greater protection. On Nov. 16, 2012, the Australian government established the Coral Sea Commonwealth Marine Reserve. It encompasses more than 380,000 square miles, half of which is a fully protected “no take” zone.

The Far North

Because of its remote location and brief dive season, Far North Queensland— off the Cape York Peninsula — is an experience only a few lucky divers will ever have. The liveaboards that offer trips here usually visit during October and November (Australia’s spring). I went just once, and I had to leave early due to a tropical cyclone that was bearing down on us. But what I saw in those few days was more than enough to make me want to return.

My first dive there was at the Auriga Bay, which gave its name to one of the first liveaboards to cruise the Great Barrier Reef. The hard-coral cap starts in 10 to 20 feet of water and then drops off to way beyond recreational diving depths. A second dive farther along the same dropoff, Rosie’s Wall, offers much of the same topography and marine life but combines these with a sense of wild remoteness To be alone at the precipice of a plunging, vertical reef and realize that relatively few divers have ever visited it is inspirational. Much of the Far North is like that: undiscovered and untouched.

At Northern Small Detached Reef whitetip reef sharks and squadrons of barracuda patrol the waters. Named for its topography, Grand Canyon features steep walls washed by spectacularly clear, electric-blue water. Sweetlips, parrotfish, anemonefish and fusiliers are found all over the place. It’s a challenging site for liveaboards to visit because there is no safe anchorage, so trips here depend on weather conditions.

At the Great Detached Reef we had dives in which sharks, barracuda, fusiliers, bluelined snapper, moray eels, potato cod and turtles would all appear over the course of 3,000 psi. Perisher Blue is a hard-coral wonderland — enough to make one believe in the health and bounty of the sea all over again. I saw at least three cuttlefish on that dive; by the end of the trip I had pretty much stopped photographing them given their abundance throughout the range.

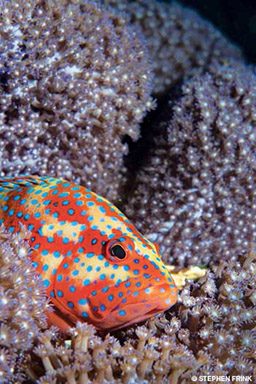

The best dive of the day and probably the best of the trip was a site simply named The Pinnacle. Up to that point we hadn’t seen much in the way of soft coral, but here we dived into stellar visibility and magnificent decoration. The spire rose from a depth of 120 feet to within 15 of the surface, and each circumnavigation revealed a different wide-angle wonder. Gorgonians punctuated by hawkfish, huge soft-coral trees and clouds of wrasses dominated the view. Closer inspection revealed coral grouper, scorpionfish, lionfish and pufferfish. The Pinnacle was so good we did it as a night dive, which was spectacular, and as an early morning dive, which was even better.

Raine Island, a marquee destination of Far North itineraries, is famed as the nesting site of the world’s largest population of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). David Doubilet, who famously covered the island for National Geographic in 2009, described it thus:

“The turtles begin to arrive at Raine Island in early October. Males arrive first, full of anticipation after a 1,000-mile swim. When the females arrive they mass outside the reef. At dusk they cross the reef, gather in the shallows and crawl onto the island under cover of darkness. This is prime reptile real estate: there may be as many as 10,000 females on the island laying eggs in one night. It is bedlam in slow motion, with turtles arriving, digging, uncovering another nest and covering theirs. At dawn though, the place was deserted as the sun rose to illuminate an island mangled by tracks of the silent horde.”

Encountering more than 250 turtles during an hour in the water is common when you visit during their breeding season (October through February). Adding to the drama during the turtles’ nesting season, tiger sharks come in for one of their favorite meals.

My final dive in the Far North before we evacuated in anticipation of huge cyclonic winds was at Sushi, a reef flat beginning in only 10 feet of water. The shallows provide huge tridacna clams, hard corals and the ubiquitous cuttlefish, one of which was laying its eggs into the crevices as protection from predators. But the Pacific double-saddle butterflyfish knew the routine and repeatedly swarmed in like pirate raiders, eager to scarf up the eggs.

I wish the weather would have allowed us to continue northward, for the chart showed we were edging ever nearer to the remote reefs separating Australia and Papua New Guinea. Yet, having that trip truncated is merely inspiration to return. With Cairns so close and convenient, the offshore attractions so photogenic and biologically diverse and the Australian people so warm and welcoming, Tropical Queensland by liveaboard remains one of diving’s great adventures.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2013