It was Thursday morning, Sept. 10, 2015, and I was eagerly waiting to hear from George Koutsouflakis, Ph.D., director of a new wreck survey. He was leading the dive team from the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities on a long-planned underwater wreck survey mission to the Fourni Islands.

“This new mission had risks greater than any other mission I had been involved in,” Koutsouflakis said. “We would be operating in a new area — completely unknown — with a new team.”

Two years earlier I had the honor of diving with Koutsouflakis on a newly discovered ancient Roman shipwreck that he had found off the southeast coast of Greece. That single dive with him turned out to be one of the highlights of my diving career, and it sparked in me great enthusiasm for ancient shipwreck diving. I have been diving on underwater wrecks for many years, mostly in the North Atlantic, but this was something quite different for me.

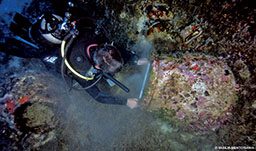

As we descended through the water column, a spectacular debris field came into view. This was a deep wreck, so the ancient artifacts were intact, adding to my excitement. Koutsouflakis and I surveyed the footprint of this Roman shipwreck and its contents, and I could not help but think of the long-lost history of this find and how honored I was to be the first diver outside of the Greek archeological diving community to visit this historic treasure. After the dive Koutsouflakis told me about the history of the wreck, its trade route and cargo.

“This Roman wreck is loaded with a main cargo of Lamboglia 2 amphorae, which are wine containers made on the Italian peninsula,” he said, “with a secondary cargo of wine amphorae originally from the island of Rhodes. Rhodes was famous for its wine and was one of Rome’s biggest suppliers. So 90 percent of the cargo on this wreck was wine, and it originated from Italy. The wreck is dated between 130 and 80 BCE.”

What we could not see intrigued me the most. We were looking at the top deck of the ancient ship, and there were two more decks below the visible debris field that were covered by sand. An enormous trove of artifacts lay beneath just waiting to be viewed.

Three days later I was invited to join a team of Greek underwater archaeologists that was working on an ongoing underwater site just off the island of Poros. Christos Agouridis, a friend and colleague of Koutsouflakis, invited me to dive with his team at Koutsouflakis’ behest. This site was an ancient Mycenaean shipwreck dated to 1200 BCE. I spent the night in base camp with the team and in the morning headed to the wreck site aboard their support vessel. They were in the process of 3-D mapping the wreck, uncovering its artifacts and documenting their finds. The team, made up of both male and female Greek divers, had training in underwater photography, archeology and architectural design, and several seasoned commercial divers filled out the ranks. I was amazed by the team’s experience and impressed with the passion they showed for their work. The experience also made me aware of the enormous challenges these kinds of underwater operations face.

Fast forward to today, Sept. 10, 2015 — I am excited to be joining the team again. This next underwater survey would take us to the Fourni archipelago, a group of 13 small islands in the eastern Aegean Sea just off the coast of Asia Minor. It has long been thought that these islands, right in the middle of ancient maritime trade routes, could be very fertile ground for ancient shipwrecks. It will be quite an undertaking, and the pressure on the team is enormous.

I got word from Koutsouflakis that the mission was on. The team would be mobilizing in Athens on Monday, Sept. 14, 2015. The support vessel would leave Athens that night and meet the team early Tuesday morning on the island of Fourni Korseon.

Eight of us in the Greek dive team boarded the 4 p.m. Mykonos Ferry for the 11.5-hour ride from the port in Piraeus (Athens) to the Fourni Islands. The team had packed dozens of tanks, a rigid inflatable boat, two vehicles, provisions, water and a compressor for the long ride to the islands.

We would meet the rest of the team on the island. Team members from the RPM Nautical Foundation, including survey co-director Peter Campbell, would join us that morning. After a briefing and some first-day site planning, we readied our gear for the next morning’s dives. I think we all knew it would be a very difficult mission. Mounting an underwater ancient-wreck survey from a remote island is a challenge for any dive team. The island terrain is difficult to traverse, and 78 miles of coastline is mostly accessible only by water. We established a base camp on the west side of the island and a secondary camp on the east to enhance our exploration capabilities, and this required overland transport of the compressor, tanks, rigid inflatable boat and dive gear.

After the team’s first few dives, the existence of an abundance of ancient shipwrecks was becoming crystal clear. We found huge clusters of intact amphorae along with evidence of additional ancient shipwrecks. On the first day the team found the remains of a Roman-period shipwreck. By day five they had found an additional nine wrecks, and by day 13, a total of 22 wrecks, some of them more than 2,500 years old. These finds represent 12 percent of all known shipwrecks in Greek waters. Could this be the ancient shipwreck capital of the world?

The team’s archaeologists were now in the process of 3-D mapping the wrecks and selecting samples of amphorae for inspection and study. Of the 22 wrecks the team found, the earliest dated to 700 BCE and the latest to 1500 CE. Some have called this the archaeological find of the year.

“All of the shipwrecks were left intact on the seafloor for future generations of divers and scientists to explore, except for one representative artifact from each wreck,” Campbell said. “These will be conserved, analyzed, studied, and when the artifacts are stable enough, archived for future researchers to study. Some may be sent to a museum for future display. Each artifact has an identification number and a report attached to it.”

On the team’s final day on the island, we shared our finds with the island’s mayor and residents. The residents of this tiny archipelago are now the supreme protectors of these great ancient antiquities.

This experience elevated my enthusiasm for ancient shipwreck diving to a new level, and working alongside this team was an absolute honor for me. They are some of the most passionate, professional people I have ever met, and they do this work not for financial reward or fame, but for the preservation and protection of their country’s historical artifacts.

The team will return next year to continue this amazing wreck survey, for this is one of the greatest opportunities in recent years for archaeologists to search the ocean floor for ancient underwater treasures. Who knows what other wonders will be found?

Note: Funded by the Honor Frost Foundation, this Fourni survey operated as a partnership between the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities and RPM Nautical Foundation.

Explore More

Watch this video to see more about the 22 ancient shipwrecks that recently were found in Greek waters.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2016