Night doesn’t get much blacker than this, Korvettenkapitan Ruggeberg thought. He and his crew of the U-513 had just crossed the North Atlantic for their first war patrol. Conditions were now textbook perfect to use the steamer they were following to slip into the bay and sit out the dark night on the seabed.

Lying in the mud at 80 feet made for a restful night, but at 1045 hours the next morning, general quarters sounded, and Torpedoman Second Class Hans Grubber scrambled to his duty station. He felt like he did on his first date, complete with sweaty palms. He and his torpedo crew loaded both “fish” in record time, and he drummed his fingers nervously on the air-pressure lever. At 1107 hours Korvettenkapitän Rolf Rüggeberg gave the order to fire, and the ship-killing torpedoes were away.

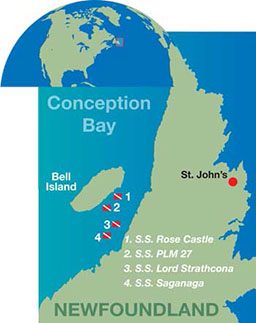

Twenty-four atmospheres of air pushed the 3,500-pound torpedoes out of their tubes — and they promptly sank to the bottom. In all the excitement of his first live combat action, Grubber forgot to switch the torpedo batteries from “charge” to “fire.” The green crew of the U-513 recovered quickly, however, and proceeded to sink the S.S. Saganaga and the S.S. Lord Strathcona on that day, Sept. 5, 1942. Two months later the U-518 under Friedrich Wissmann sent the S.S. Rose Castle and the PLM-27 to join their comrades at the bottom of Conception Bay.

Despite these shipwrecks, Newfoundland doesn’t come to many divers’ minds when considering dive destinations. In fact, only a very few have braved the North Atlantic in these parts. My traveling companions and I really didn’t know what to expect except mind-numbingly cold water. As it turned out, we would be as astonished as Grubber with our first visit.

Most of the diving — but certainly not all of it — is done at the southern part of the island near the city of St. John’s. Enormous Conception Bay, which contains numerous reefs and other underwater treasures, lies nearby. Bell Island in Conception Bay is the home of what was once one of the largest iron-ore mines in North America. The 5.5-mile-long by 2-mile-wide chunk of rock drew the attention of German U-boats during World War II, and it’s the resting place of the four ships mentioned previously.

Those four shipwrecks are the island’s signature dive sites, and the remarkable degree of their preservation should not be missed. Despite some heavy damage that you’d expect of vessels sunk in war, much of the ships’ equipment and bric-a-brac and even sailors’ personal effects still exist in place. One reason they’re so well preserved is the less-than-warm water in which they lie.

Our first dive was on the S.S. Paris-Lyon-Marseilles, or PLM-27. It’s the shallowest of the four, and it’s smothered with marine life. Its prop and rudder are intact, as is most of the stern. There we encountered our first lumpfish, and we all fell in love with the odd critter. It seems to be part frogfish and part puffer rolled into one, and there’s an amazing sucker (adhesive discs) on its belly it uses for hanging out. The PLM-27 was one of the ships lost during the second attack in November 1942. It sank in less than a minute with 12 crewmen aboard.

The second dive took us to the S.S. Saganaga. A little deeper at 110 feet to the bottom, the Saganaga went down with 29 men in the September attack. It’s even more coated with marine life, which includes vast numbers of metridium anemones, crabs, fish and colorful sponges. Of the wrecks in the area, the Saganaga also has the most deck swim-throughs, which make for a very three-dimensional experience, even without penetration.

Both the S.S. Lord Strathcona and S.S. Rose Castle are located in slightly deeper water but are consequently more intact. If you have the training and experience, the Rose Castle provides almost limitless potential for penetration. The Strathcona is the only ship that did not suffer any casualties, as all managed to abandon ship before the torpedo struck. The Rose Castle lost 28 sailors.

One of the amazing things to see on these ships is the quantity of wood that is still in place — there are even intact hatches. These vessels have been down longer than the wrecks in Chuuk but are in much better condition. In addition to the cold temperatures, pillaging has been kept to a minimum out of respect for these gravesites. It’s worth noting that the RMS Titanic rests only 350 miles away, so, yes, it’s cold — but it’s not as bad as we thought it would be. From around 60 feet and shallower you can expect temperatures in the mid- to upper-40s (°F) with the surface temperature in the mid-50s. On the deeper wrecks such as the Rose Castle, it can get down to the mid- to upper-30s deeper than 100 feet. As long as you’re dressed properly, 40- to 50-minute dive times are quite possible. However, these are summertime temperatures.

Conception Bay is well protected, and flat water is the norm. Boat rides don’t get much easier, and there are many shore-diving possibilities. We took advantage of a popular beach entrance in the fishing village of Dildo. This was one of the last whale-processing plants in Newfoundland, and an enormous whale graveyard is located just offshore in 50 to 80 feet of water. It’s one of the sobering reminders of why this part of the world was settled to begin with. Whales here have it much better now, and snorkeling with humpbacks at the right time can almost be guaranteed. The boat rides are short, and whales are usually spotted immediately; you just have to find one or two that want to play. Slowly swimming with these gigantic marine mammals as they watch you intently is truly something to cherish.

Our group was unanimous in wanting to come back as we felt we hadn’t even scratched the surface of what’s available. On some of our shore excursions we could see stunningly clear secluded coves and reefs just begging to be explored. The accommodations, dive boat, and crews of Ocean Quest Adventures were top notch. Yes, the water is cold, but the different marine life, authentic ship wrecks and warm, generous people go a long way toward balancing the need to pack a drysuit.

How To Dive It

Conditions: The surface conditions are quite mild in the summer. Even when winds kick up they rarely make more than a small wind-chop on the bay. It’s very much like the Pacific Northwest. Water temperatures are in the 40s (°F) for most of the summer; below 100 feet it’s usually down into the 30s. The main diving season is from May through September, with the coldest water temperatures in May and June. Early in the season icebergs may drift into the bay, and, yes, divers can visit them. One year an iceberg brought a narwhal with it. Unless you’re a polar bear, a drysuit and proper undergarments are a must. Currents are rare, and visibility can reach 100 feet (40-75 feet is normal). Air temperatures vary but range from the 50s to the 80s in the summer.

Getting There: St John’s is the point of entry for international visitors. Direct flights are few and mainly originate in the northeastern U.S. A small number of airlines, including United Airlines and Air Canada, service Newfoundland. The time difference from Eastern Standard is 1.5 hours ahead. Trekkers from the eastern provinces can drive here via the Trans-Canada Highway and a ferry ride.

On the Surface: If you come to Newfoundland in the summer you had better like water and the color green. There are literally thousands of miles of rugged, forested coastline and dozens of quaint fishing villages that seem almost frozen in time. But if you come expecting to find folks living in igloos, you’ll be disappointed. St John’s is a thriving modern city with some 200,000 people. Oil is the new “fishery,” and the economy is booming. City delights include just about any type of pub or restaurant you can imagine. And because the city was founded in 1623, there’s no shortage of historical landmarks, museums or unbelievable scenic overlooks. There are accommodations in the city proper, but most diving visitors stay in South Conception Bay, about 30 minutes away from St. John’s.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2013