Wisdom teeth are permanent molars that usually emerge during the late teens or early twenties. It’s not uncommon for these teeth to be associated with pain or complications. Dentists often recommend having the wisdom teeth removed. Any tooth removal can be concerning for divers since keeping a scuba regulator in place means securing it with your bite.

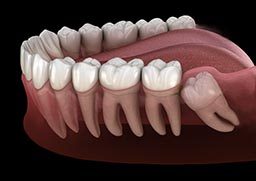

“Wisdom teeth” is the common name for the third molars. There are typically four wisdom teeth. They are the farthest back tooth on each side of the upper and lower jaws, and their location and large size make them perfect for grinding food. They are vestigial teeth from our hominid ancestors who had to grind tough, fibrous vegetables. Genetic variation in jaw and tooth size, a diet less stimulating to jaw growth and lack of tooth loss contribute to a lack of space for the wisdom teeth. In a healthy mouth with enough space, the third molars may not need removal.

Wisdom Tooth Complications

The physical eruption of wisdom teeth can cause discomfort. Erupted third molars are often malformed and can be associated with weakened soft tissue. They are difficult to clean, which also makes them susceptible to decay and soft tissue infections.

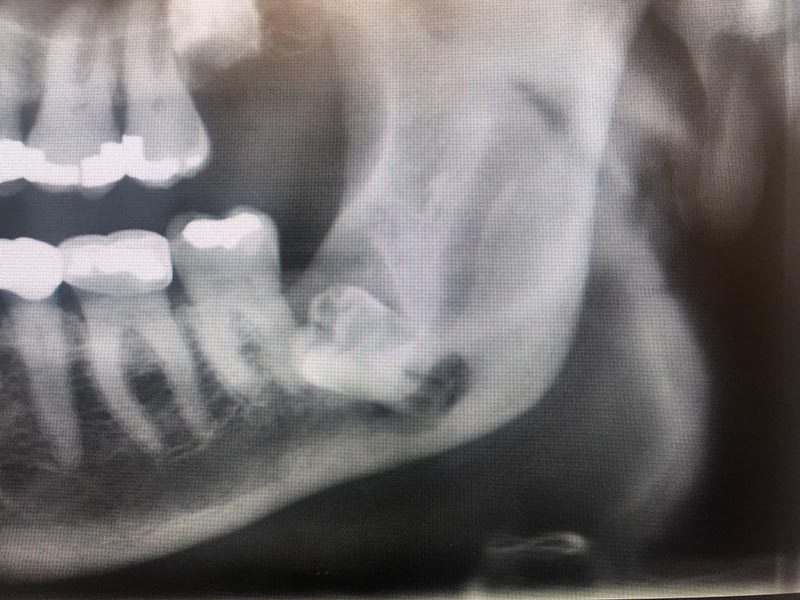

Approximately one-third of all wisdom teeth do not fully erupt into position. This lack of eruption is called impaction. Some third molars remain deep within the jaw; others are only slightly malpositioned or have a small flap of soft tissue overlying part of the tooth. Impaction impedes proper cleaning, which can lead to a buildup of bacteria that may cause an infection. This infection, called pericoronitis, typically involves the soft tissue around the crown of a partially erupted third molar. Treatment of pericoronitis consists of oral antibiotics, chlorhexidine rinses and warm saline rinses. Problems with a wisdom tooth can lead to decay and infection in the adjacent second molar.

An infected third molar will usually cause pain and swelling. As the infection progresses, swelling increases and can cause trismus (locked jaw) or limited jaw opening. Some infections are minor while others may be life-threatening. One dangerous complication is when the position of an infected lower third molar lets the infection extend into deep spaces in the neck or affect the airway.

Impacted teeth can be associated with cysts and tumors, but the most common problem is infection. Less frequently, associated cysts can become infected or grow large enough to weaken the lower jaw. A weakened jaw can fracture with minimal trauma.

Complications From Extraction

Among the possible complications following wisdom tooth removal are dry socket, extraction-site infection and acute maxillary sinusitis.

- Dry socket is a painful condition resulting from the loss of a blood clot in the extraction site. The standard treatment is oral antibiotics and medicated dressing changes.

- Infection of the extraction site can occur immediately after the extraction and continue to be a risk for about a month. It is treated with oral antibiotic therapy and often a drainage procedure.

- The maxillary third molar is usually close to the maxillary sinus and can affect the thin bone between the tooth and the sinus. This can result in infection and, rarely, an opening from the sinus into the mouth. An uncomplicated acute maxillary sinusitis usually responds to antibiotic therapy. A chronic opening or chronic sinusitis might require surgical intervention.

Implications in Diving

Plan any dental surgical procedures well ahead of a dive trip, especially a trip to a remote location. There are four primary circumstances in which wisdom teeth may affect diving.

- Tooth removal before diving: There is a possibility of unrecognized bleeding from the extraction site and the flow of compressed gas into the oral cavity. Avoid diving immediately after dental extraction, even if there were no complications.

- Problems during a trip: Dental care can be challenging in a remote location; a cavity, toothache, soft tissue infection or tooth squeeze has the potential to disrupt a dive vacation. Most of the time you can avoid these complications with adequate prevention. If you have not had your wisdom teeth removed you may wish to inquire about the need to remove them. Maintain your dental health as part of remaining fit to dive.

- Diving after removal of an impacted wisdom tooth: Ask for advice from the surgeon who removed the tooth or teeth. Numbness, as well as dental and muscle pain, may impair your ability to hold a mouthpiece in place. A loosely held regulator can be a drowning hazard. Most specialists recommend a minimum of four weeks after an uncomplicated wisdom tooth surgery. Even after that, complications are possible. Deeply impacted wisdom teeth that result in nerve damage, sinus complications or weakening of the lower jaw might require months to heal.

- Jaw softness: This is much less common. Impacted teeth can be associated with large cysts or chronic infection, which can weaken the lower jaw or interfere with standard drainage of the maxillary sinuses. When this happens, the end of the jaw remains more fragile while healing. Such an issue would appear during a routine examination with appropriate imaging. Returning to dive too early could increase the risk of fracture.

Other Considerations for Divers

- If there is still some localized edema (swelling), off-gassing of nitrogen from the area during decompression may be impaired. Although decompression illness in a small area of the jaw seems unlikely, this could be a problem.

- Some types of pain medicine could pose a risk during dives. Drugs like codeine, oxycodone and other narcotics could synergize with the narcotic effect of inert gases (nitrogen narcosis), dangerously impairing performance and judgment underwater.

- If you still have symptoms after the extraction procedure, you should avoid diving until you are symptom-free.

Guidelines for Diving After Dental Surgery

- Wait for a minimum of four to six weeks or until the tooth socket and/or oral tissue has healed sufficiently to minimize the risk of infection or further trauma.

- Don’t dive until you have discontinued using medication to control pain resulting from the surgery. Thus you will avoid any risk of drug interaction with nitrogen.

- Make sure you can hold the regulator mouthpiece without pain or discomfort for long enough to perform a planned dive.

- For more information on dental health, see the Mayo Clinic’s guide.

Special thanks to Nicolas S. Veaco, D.D.S., M.D., M.S. for his contributions and revisions