Excellence in the extreme

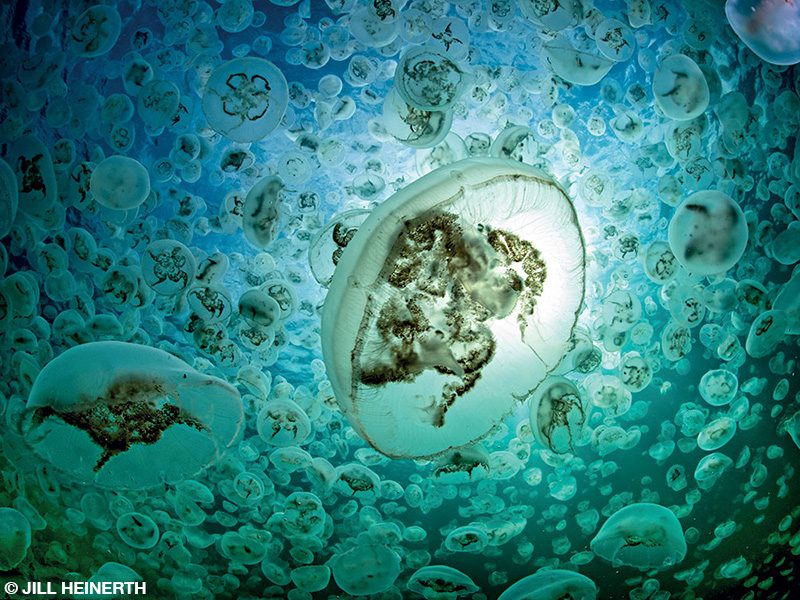

I remember a feature article in an old Ocean Realm magazine about an expedition that Bill Stone led to map Wakulla Springs in northern Florida. I don’t recall all the details, and at the time I knew very little about cave diving culture, so I marveled at the photos documenting the creative lengths to which these divers went to explore so far and deep into a little-known cave system. I wondered who would (and could) do such a thing. A young cave diver named Jill Heinerth was the only female among those elite cave divers. She would do such a thing and has made a career out of going deeper and farther, artfully bringing home images to tell the tale.

Being a world-class cave diver probably wasn’t the dream that first resonated with her as a young child growing up in Mississauga, Ontario. The Apollo mission she saw on TV captured her imagination and fueled her desire for adventure. She shared her aspirations with her mother, who cautioned, “There are no girl astronauts and no Canadian ones either.” Discouraged, she took a more traditional path, earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in visual communications design, which led to a career in advertising communications.

After starting a small ad agency in 1988 outside of Toronto, Heinerth soon had mainstream clients such as Nike on her roster. At the beginning of the personal computer age, she was able to apply her art school experience in typesetting and traditional design technologies to the new science of computer graphics. She was a skilled early adopter, and her agency flourished.

As her career evolved she realized she wasn’t going to be flying to outer space, but inner space was an option. Having learned to dive while in college, Heinerth became an instructor and ran trips to the Fathom Five National Marine Park at Tobermory, Ontario. She spent her days at the drafting table while desperately seeking a way to get underwater more often.

This was a time when the kind of diving she wanted to do needed more tools than recreational diving afforded. She recalls, “Nitrox was a travesty, and deep and technical diving were whispered about in garages.” With a drive to get out of the design studio and turn the trajectory of her career, she sold everything she owned in Canada and moved to the Cayman Islands.

Stephen Frink: When you moved to Grand Cayman, I was frequently diving there and doing articles for Skin Diver magazine. How did our paths never cross?

Jill Heinerth: Maybe because I was on the East End, which was remote in the early 1990s. I used to go on vacation to the Cayman Diving Lodge, and during one dive holiday they found themselves in a bind for staff. They asked if I could help for a month. This was at a very developmental time in my life, so I went for it. I did whatever was needed: guiding dives, teaching scuba, filling tanks. In my spare time I tried to improve my underwater photography, and because I loved to write, I hoped I could place some articles in dive magazines.

I began my cave diving there. There is a cave system on Grand Cayman that was unknown at the time, but I heard stories of ponds where cows gathered and that the ponds would magically transport turtles to the sea. I had never trained as a cave diver and quickly discovered I needed to know more than I knew. But I explored what is likely the same cave system that is now a tourist attraction on the East End called Crystal Caves.

In the following years, I was exploring some of the world’s longest and deepest underwater caves. By 1997 I was diving at Wakulla Springs with the U.S. Deep Caving Team, working on the world’s first accurate 3D digital map of an underwater cave. For that project I spent two years living in a broken-down trailer behind the dive shop that my husband and I owned on Florida’s West Coast. I was diving with a Cis-Lunar Mark V rebreather and working with Dr. Stone on how to accurately map a cave system up to 300 feet deep in any visibility we encountered. We had dive missions with bottom times (including decompression) of 22 to 24 hours.

How did you get from pure push-the-limits exploration to bringing home the story in stills and video?

I attribute that to my friend Wes Skiles. In the mid- to late-1990s Wes and I were on opposite teams exploring Sistema Dos Ojos and Nohoch Nah Chich in Mexico. In those days he was losing his desire to do the deeper dives after being bent too many times. When we found ourselves together at Wakulla Springs in 1997-98, he asked if I would run the deep camera for a National Geographic TV special. I jumped at the opportunity.

That event was pivotal in my career. Up to that point, outsiders saw cave diving as an adrenaline sport and viewed cave divers as foolish risk-takers who tried to go the deepest or the longest. It was more than that for me. At Wakulla we were doing ground-breaking survey work, modeling the caves and showing the world precisely where the drinking water conduits were beneath our feet, and we were connecting everything with GPS. I could teach people about the science of the aquifer.

Swimming through the North Florida cave systems was like swimming through the veins of Mother Earth, in the very sustenance of the planet. We could detect the presence of nitrates from fertilizers and septic tanks. We could see places such as Crystal River change from saltwater intrusion to the point where we saw marine life growing on the pilings of what was once a pristine freshwater flow. We could watch the flow of some caves drop to the point where the tunnels eventually collapsed and filled in.

Doing what you’ve done for as long as you have, you must have had some close calls. What scared you to the point where you felt fortunate to have survived?

The single most frightening event happened in 2001. We had pitched a film to National Geographic about cave diving through conduits inside the B-15 iceberg in Antarctica. Iceberg caves were hypothetical, and diving them would be a first. With Nat Geo’s support, we would shoot a film we called Ice Island.

I knew we needed to use rebreathers, if only for the extension of bottom time and protection from the cold. The risk of free flows and the finite gas capacity of open-circuit diving were too risky in my mind. The choice to use rebreathers may have saved our lives.

On our very last dive we found ourselves in unbelievable currents in a cave within the iceberg, clawing our way hand over hand. I remember Wes yelling through the rebreather mouthpiece to ask for help lugging the heavy high-definition camera. I was thinking, “Screw the camera. We might die!” A one-hour dive turned into three hours with the current working against us. Even when we got to the exit of the cave, vertical currents were pressing us down. To frantically climb an underwater ice wall, we evicted tiny ice fish from their burrows, using their homes as little fingerholds that would help us claw our way back to the surface.

We obviously made it, but as we prepared for another dive a few hours later, the entire iceberg exploded and turned to slush, throwing up a massive wave that rocked the boat and our confidence. The melting ice might be a climate change story, but the sidebar is that this was the nearest I ever came to not getting home from an assignment.

It seems your career has evolved into a hybrid of shooting, writing and public speaking. What is your primary motivation?

Whatever I need to do to stay in the water is what I will do. I’m endlessly curious. I’ll ask scientists what they need for their underwater research, and I’ll try to be their eyes and hands to tell the visual story. It seems all my work these days connects to water quality and climate change. In my book Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver, I share scientific projects that relate to both areas. In my recent film Under Thin Ice, I film charismatic megafauna such as narwhals, walruses and polar bears to tell the story of climate change. I’m an educator at heart, and I seek to create visual connectivity with the most pressing global challenges we face.

How do you manage to excel at both still photography and video?

If I had to choose, I’d be a still photographer, but gratefully I don’t have to pick one over the other. I like the challenge of being adept at both disciplines. For stills I like to use a Canon 5D Mark IV in an Aquatica housing, and for video projects where I must stay nimble I use an Aquatica housing with a Panasonic Lumix GH5. Each camera is small enough that I can carry both, even with dedicated strobe lights for the Canon and video lights for the Panasonic. It depends on the project — sometimes I shoot a RED or an Arri video camera in Gates housings. If it has a shutter, I’m OK with it. I’m agnostic when it comes to photography equipment. A camera is a tool that leads to a result. I want the best tool I can use, of course, but the kind of exploration we are doing will help determine the optimal choice.

In the end, I want to tell a good story. I need the technical dive skills to do it safely, and I want to be visually creative to communicate differently or better. I don’t necessarily know what that story will be when I go out into the field, but that’s part of what drives me — along with doing whatever I need to do to stay in the water. That motive hasn’t changed much since I decided that I needed to be somewhere other than running an ad agency in Ontario.

Explore More

© Alert Diver — Q1 2020