“In his passion, Ernie took the road less traveled. When color photography dazzled us with the revelation of color underwater, he saw something different and courageously continued to explore his art in black and white … as light enters the water; the brightest colors are filtered out … the reds, oranges, and yellows being the first to disappear. So, by choosing a palette of black and white, Ernie captures a quality that is more true, more revealing of the sea, than the color images that so easily seduce us.”

— Jean-Michel Cousteau in the forward to Ernie Brooks’ 2002 book, Silver Seas: A Retrospective

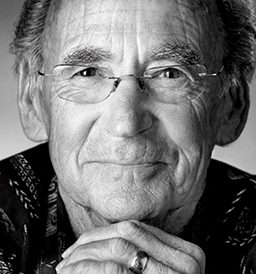

The homage to Ansel Adams is almost too predictable when describing the photography of Ernest H. Brooks II. That they are both masters of the art and science of black-and-white photography is obvious when reviewing their body of work, although Adams specialized in landscapes of the American West, while Brooks derives his inspiration from beneath the waves. It is somehow appropriate that their photography is being exhibited in tandem in an impressive traveling exhibit titled “Fragile Waters.” Each communicates a unique vision and underlying passion to preserve and protect his muse, mother earth.

In the Brooks family, photography is a long and honored tradition. At the turn of the century Brooks’ paternal grandmother photographed nature with glass plates and the very early technologies for capturing still images. In the next generation, Brooks’ father was sidetracked from his studies in commercial art when he discovered Kodak 8×10 sheet film that he could process in his home darkroom. By the late 1930s his passion for photography was being passed on to his son; by the time Ernest II was enrolled in kindergarten his fingernails were stained brown from immersion in fixer, the final element in black-and-white printmaking.

It may be hard for today’s digital photographers to imagine the countless hours Brooks spent with his father learning photographic techniques in an analog darkroom, but doing so clearly forged his path in life. I can relate a little, for I’ll never forget my first time standing in a black-and-white darkroom, illuminated only by the dull glow of a yellow safelight, and seeing that first print emerge in a tray of Dektol. Today, viewing digital images on even the best-calibrated monitor somehow fails to invest an image with the respect and significance a wet darkroom can instill.

Maybe it was the tedium of the processes. The film had to be developed just right, to exacting standards of time and temperature, dipped in Photo-Flo so it wouldn’t water spot and then hung to dry. Once sleeved, a contact print was made, sandwiching the negatives directly to a sheet of paper coated with a photosensitive emulsion. That paper would be processed in a tray of developer, rinsed and put in a solution to “fix” it with permanence. It would be dried, and only then could one get some sense of the potential of any negative from the roll.

The photos that were worthy would next be gingerly placed into a negative carrier (if they were scratched they would be essentially useless), then into an enlarger and then projected onto another piece of emulsion-coated paper of a given contrast grade. The darkroom magician might use a bunched fist to dodge a part of the print that appeared too light, or he might form a tiny cone of light to burn a bit more brightness on an area that was too dark. Next that paper would go into the developer, gently rocked back and forth, processing by inspection under that same yellow safelight until just the right tones emerged. For some prints, still other processes might be applied. There could be a sepia toner to make a photo look aged or a selenium toner to achieve yet a different look. By the time the fixer, wash and drying were done there would inevitably have been several hours, or even days, invested per image — and that’s assuming there weren’t imperfections that had to be “spotted” with a fine camel-hair brush and a special solution meant to mimic the tones of black and white, as that would add even more hours.

Clearly, this is a different mindset and a different discipline that has guided Brooks all these years. It’s why he could be satisfied with taking only 12 shots per dive with his Hasselblad Super Wide camera. In fact, he usually ended up with fewer than that; his protocol was to take the first shot as a kind of a throwaway, just to make sure everything was working before happening upon a once-in-a-lifetime photo-op and coming to the crushing realization that the camera had jammed. Then there was the last shot, the one he’d save in reserve just in case something amazing swam by on the way back to the boat. Just 10 frames per dive defined Brooks’ world for so much of his life. Judging by the quality of his work, 10 frames served him very well. While today’s photographers enjoy a virtually limitless imaging capacity on every dive, the ability to pace a dive to just 10 shots is rare. Perhaps this — combined with the aesthetic to see the sea in black, white and shades of gray — has forged a vision unique in underwater photography.

Stephen Frink// Photography is the “family farm” for you. Your father founded what is perhaps the most famous educational facility for photography in the world with Brooks Institute. How did all that come about, and how were you involved?

Ernie Brooks// When I was very young my dad loaned me his camera, and I photographed all the kids in my class sitting on a slide on the playground. That was 1939 in Lompoc, Calif. We processed the film and printed the photo, and it was used in the local paper. I guess I first became a commercial photographer in kindergarten!

But the inspiration for a teaching facility happened in 1943 during World War II, while my dad was working in Dayton, Ohio, for the Civilian Army Corps. He devised a curriculum to teach in-flight and ground-to-air photography to Army and Air Force personnel. It was soon after this that he met Heinrich Weston, from Santa Barbara, Calif., who convinced him that there needed to be an educational facility to teach photography to the many returning veterans who needed careers and had the GI Bill to help fund them. On Oct. 17, 1945, they opened the doors to Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara, dedicated to the pursuit of the art, science and business of photography. They started with 35 students that first year, and today there are more than 1,200 students enrolled at Brooks. They teach cinematography, filmmaking and scriptwriting in addition to all the commercial and fine art photography classes offered. There are now 8,500 alumni worldwide.

SF// I can’t imagine underwater photography was a natural progression for students at Brooks, yet that program has graduated some of the top shooters in the field. How did that program come to be so successful?

EB// My dad enjoyed snorkeling, but he never really got into scuba or underwater photography. When I joined Brooks Institute as an instructor in 1960, we were already running field trips to Sonora, Mexico, to photograph people and seascapes. The students would snorkel and swim quite actively while there, so it seemed underwater photography would be a natural extension. That first year I took a group of students there and learned how to make and use housings to protect our land cameras against the effects of immersion in the sea.

More and more of our students seemed to enjoy making a statement in the underwater world, and in the decades between 1960 and 1980 it absolutely ballooned. David Doubilet took our class when he was 17, and Chuck Davis, Cathy Church and Jim Church were enrolled there as well. Al Giddings, Bob Hollis, LeRoy French, Bill DeCourt, Chuck Peterson, Ron Church and others would meet at Brooks Institute and formed the Academy of Underwater Photographers, creating exhibits, seminars and products for the nascent underwater photography industry. Ron and Valerie Taylor spent many days in the water working on Brooks projects with students; Jean-Michel Cousteau and Philippe Cousteau would dive with us as well.

It was kind of like the early days with my father when Ansel Adams and Edward Weston lived just up the road in Carmel, Calif. They often needed darkroom assistants, and the Brooks Institute was one of the first places they went to recruit. Brooks was a nexus for the “Group f/64” shooters back in that era. In much the same way, the world of underwater photography came in contact with the institute, most often aboard our 57-foot former purse-seine trawler, Just Love. I enjoyed the irony that a vessel that once plundered the seas in Alaska was now being used by some of the world’s most influential underwater photographers and their protégés to celebrate the sea’s beauty and bounty in photographs.

SF// I will always associate you with one camera, the Hasselblad Super Wide. How did that affiliation begin?

EB// In 1961 Victor Hasselblad came to visit Brooks Institute and lectured on medium-format photography with his Hasselblad cameras. While visiting he saw the underwater photography I was doing with an Exakta 4 rangefinder and housing, and unbelievably he gave me a Hasselblad Super Wide C with the brilliant 38mm Zeiss Biogon lens. The lens had 90-degree diagonal coverage, not so different from the Nikonos 15mm at 94 degrees; but to achieve wide-angle underwater, Hasselblad had created a housing with an Ivanoff corrective port, and he gave me one of those, too! Given the quality of the camera and the housing, and the fact that it was prefocused at 6 feet from the front glass, that was my universe. I found and photographed things 6 feet away that fit the format of my Super Wide.

SF// You obviously are a master of the analog darkroom, but have you embraced digital as well?

EB// Yes, of course, you can’t ignore the technology. In fact, I do a lot of digital infrared black and white these days. Even my traditional analog images are now printed by digital means. Epson actually designed a paper for my “Fragile Waters” exhibit to optimize the tonalities of my black-and-white underwater images when printed with a digital inkjet. The result can be seen in a traveling show with 6,000 square feet of images now on tour to major art museums around the world.

I likewise embrace the electronic medium of the Internet; I know it is the ultimate tool for communication. My goal with my photography has been to inform and inspire people to revere and protect the ocean. If by my book and exhibitions and teaching I have done that, then I will have done my part to preserve the sea. I truly believe the best way we can impress upon the world that the sea is worth saving is by presenting the beauty within it. Only then can people grasp how important the ocean is to everything on this planet.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2011