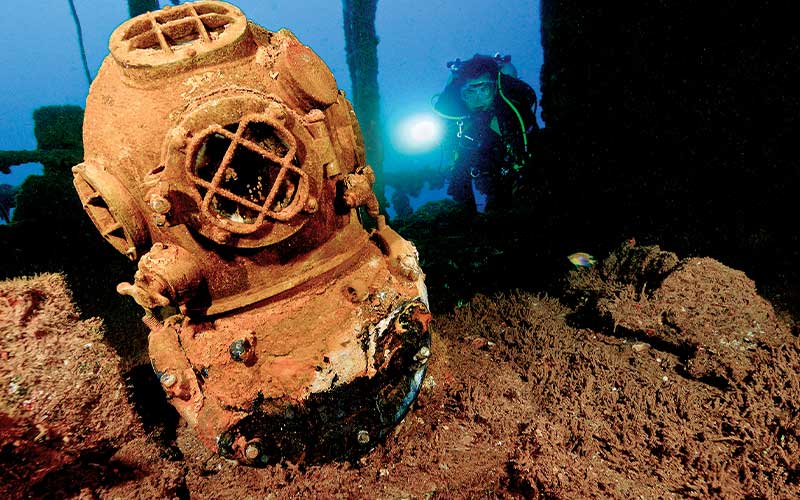

Most divers who have been certified for any length of time find themselves, at some point, interested in wreck diving. In part, this is because wrecks can be found in just about any body of water — from quarries, where old propeller planes and school buses entertain us; to rivers and lakes, where fresh water can preserve even wooden ships for ages; to the seas and oceans, where the sunken remains of humans’ seafaring history are found. Divers are fascinated by the windows on the past wrecks can be; each one is a museum of both human history and aquatic ecology, frozen in time but alive. Whatever your interest in wreck diving, it’s safe to say the knowledge, training and expertise needed to dive wrecks are as unique as the experience itself.

I have often been asked what it takes to dive wrecks safely or what training a diver should pursue to enjoy wreck diving, and my answer is always, “It depends.” Many dive professionals have heard the following stated earnestly by an overzealous new diver: “I was hoping to dive the Andrea Doria or the Britannic — what do I need to do?” My answer to this statement is also consistent: “How many years were you planning to train for the dive?” It takes a while to work up to a low-visibility, cold-water, high-current, offshore, custom-blended-mixed-gas wreck dive; you have to master each component before trying to tie them all together.

Strong Currents, Big Waves

Let’s face it, many wrecks are on the bottom because the surface conditions in the area were, at some point, less than ideal. Some of the most interesting historical wrecks are situated in especially challenging dive conditions. Divers wishing to visit these wrecks should be comfortable with high current and surge. This means lots of experience diving in the open ocean and good physical fitness. A giant stride from a pitching boat into turbulent waves can be daunting, but getting back onboard at the dive’s end can actually be more physically challenging — and dangerous. You need to be able to haul yourself, your gear and 30 extra pounds of water weight back up the ladder as well.

Every effort should be made to have equipment that is proper for the dive and streamlined to reduce drag, thereby reducing the effort required of the diver. Think you’re in great shape and this doesn’t apply to you? The fact of the matter is you are fighting physics as well as your physiology. As gas density goes up with increasing depth, carbon dioxide (CO2) retention also goes up with increased effort or work at depth. With an increase in CO2 retention, your likelihood of passing out from hypercapnia (excess CO2) or a seizure also increases. (Excess CO2 can predispose divers to seizures when using any gas mixture with a high partial pressure of oxygen.) Overexertion at depth has killed many divers via both mechanisms and is something to be avoided at all costs. A highly skilled diver will expend far less effort to move through the water than a brand new but highly fit diver. The best scenario: Be both experienced and in good physical shape with properly streamlined equipment.

Speaking of overexertion, recent research indicates diver mortality from cardiac events is a growing concern, and various means of addressing this concern were the subject of heated debates at the 2010 DAN® Recreational Diving Fatalities Workshop. Overall fitness should not be taken lightly; if you are concerned about your cardiac health, talk to your doctor, or call DAN for a referral to a doctor trained in dive medicine. If you are over 40 or have cardiac risk factors such as long-standing high blood pressure, a history of tobacco use, heart disease in the family, diabetes or other medical conditions, you can’t go wrong getting evaluated.

The Hazards of Wrecks

OK, you work out regularly, don’t smoke, keep up with your health concerns, have streamlined your gear so an occasional fin stroke keeps you ahead of the divemaster and have logged 82 Caribbean and offshore dives in the last three years. So what do you need to be concerned about down on a wreck?

Wrecks present unique hazards for those diving the outside as well as the inside of the structure. The outside of a wreck seems deceptively safe. The reality is that fishermen love wrecks as much as we do, only they seem determined to cover them in nearly invisible line that’s hard to cut and invariably has something sharp and rusty at one end. Newer abrasion-resistant line is all but impossible to cut without shears or blunt-ended trauma scissors, which I always carry. These are made of high-grade stainless steel, weigh almost nothing and can cut a penny in half. Loose netting from fishing vessels is also found covering wrecks in deeper waters. Entanglement is a leading cause of experienced technical diver deaths — it can happen to anyone. Be prepared for it with proper cutting tools. Most experienced divers have more than one handy in case they drop one or are entangled in a manner that prevents access to their primary tool.

Inside a wreck there are other concerns: metal rusting to razor-sharp edges, rooms turned to impossible and disorienting angles, furniture lying in jumbled heaps and wiring that your shears won’t cut. Insulation may fall from a ceiling, blocking a passageway while simultaneously dropping the visibility to millimeters, or an errant fin stroke might mix the paint on the walls with the water in the room, giving it the consistency of blue milk and forcing you to find a way out by fingertip. A 700-pound goliath grouper could suddenly realize you just swam into the room he was napping in — and that you are floating in front of the only exit. All these are real-world pop-quizzes I have enjoyed in the past. It turns out training for the worst-case scenario pays off every now and again, so pay close attention to your carefully chosen wreck instructor. Wreck diving can be done safely but requires training, experience and the right equipment. Don’t shortcut any of these prerequisites, or you risk failing one of those quizzes.

Getting Back on Board

So you got trained, practiced, got your gear up to speed, and your buddy calls. He has booked a trip out to that wreck you’ve been chatting about forever. A few days later, you drop down into the depths, find the wreck, explore it and are ready to ascend. The current has picked up, so you and your buddy blow lift bags from the top of the structure before you drift off into the wild blue yonder. You release the bags from a down-current rail to ensure they, and eventually you, don’t get entangled in the superstructure during ascent. Maybe you racked up a few minutes of planned decompression — no drama, you are trained and equipped for it. Twenty minutes later you have completed the dive and are on the surface — more than a mile away from the boat in a three-knot current.

If you didn’t anticipate the possibility of being alone in the open sea, your dive planning was, ahem, incomplete. The latest whiz-bang gadgets are nice to have, and there are dives where an emergency position indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) is a great idea, but you always need some basic short-range signaling devices. Everyone should carry and know how to use a signal mirror and whistle. Flares, dye and an inflatable tube usually make it into my kit for serious offshore excursions. Ask your wreck instructor how best to carry them. One system, an old wreck-diver trick believed to have been introduced by Billy Deans, is an OSC (“oh shoot can” or something like that). An OSC is made up of an old canister light with a solid lid that can hold all these items plus a small EPIRB and is watertight to depths far below your planned dive depth. If I am going way offshore to dive in a six-knot current like the Gulf Stream, I keep mine next to my light can on my belt. There’s no telling where you will be after an hour of deco on the end of a bag and string. If you’ve never spent a few hours drifting waiting for the boat, it’s memorable. Oh, I also carry a small tube of high-SPF sunscreen in my can now, too; there’s no teacher like experience.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2011