Divers know fish — or do they? A couple of decades ago a traveling diver who wanted to learn about a fish he had just seen would have to risk a severe allergic reaction brought on by contact with the rotting, moldy books found in the libraries of dive resorts or liveaboards. The poor images and baffling descriptions made it almost impossible to find the fish you thought you saw. Back then divers really didn’t know fish, and they often weren’t even interested because identifying them on site was just too difficult.

Ned DeLoach told me that when he began photographing fish he assumed the marine world was a known commodity. But after talking to scientists about where certain fish might exist in the Caribbean, it became apparent to him that even scientific knowledge was limited. Filling a niche, DeLoach and Paul Humann ushered in the modern era of diving-naturalist literature in 1989 when they self-published Reef Fish Identification: Florida, Caribbean, Bahamas.

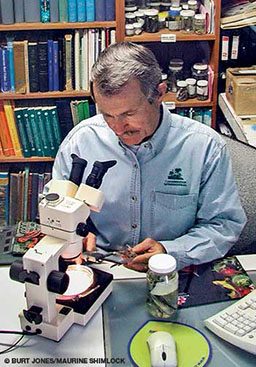

Today, increased curiosity (due in part to a growing awareness of the threats coral reefs face) and the popularity of digital cameras have spawned an enthusiastic interest in proper fish identification. No marine biologist of the past two decades has had greater influence on the direction of scientific research about coral reefs and divers’ knowledge of reef fish than Gerald Allen. Author of 36 books and more than 400 scientific papers, Allen believes his 12,000 dives distinguish him from ichthyologists who rely on data and specimens collected by others. Because he’s been on just about every reef on the planet, often sharing boats with traveling divers from around the world, Allen understands what they want to know about reef fish. I remember reading the little book he produced with Daphne Fautin about anemonefish and coming away surprised to have learned that specific anemonefish lived with specific hosts. No one before Allen had put this information in an easy-to-understand format for divers who wanted to absorb a few interesting facts along with their nitrogen.

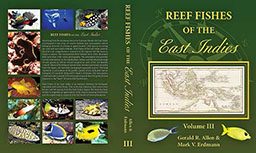

Inspired by a grad-school mentor’s gift — Max Weber’s and L.F. DeBeaufort’s 11-volume Fishes of the Indo-Australia Archipelago (published between 1911 and 1962) — Allen has just published, along with co-author Mark Erdmann, a three-volume set, Reef Fishes of the East Indies, the first truly comprehensive, encyclopedic and photographic coverage of reef fishes from the world’s most biodiverse region: the Andaman Sea eastward through the Solomon Islands. With 2,631 species descriptions and even more colorful images, this book represents a distillation of Allen’s lifelong passion for tropical reef fish.

“Weber and DeBeaufort was the bible, as far as I was concerned,” Allen said. “But as time went on I realized it was really out of date. For example, the section on shrimp gobies, which was completed in 1953, well before sport diving was massively popular, described 16 species illustrated by black-and-white images — the only kind in the entire book. In our new book, 83 shrimp gobies are described, and they’re all illustrated by onsite underwater images. What I’ve wanted to do since my 1971 fieldwork in Papua New Guinea was marry my own passions (and the similar passions I saw in sport divers around me) — diving, photography and ichthyology — into a new, improved encyclopedia of fishes.”

It took four years, and it wasn’t easy. Besides the vast subject matter, a few months after a major donor offered to fund his seminal work Allen suffered a serious spinal injury. In 2009, after spending a month in a U.S. hospital, he was medevaced home to Australia, where he endured another long hospital stay and months of in-home rehabilitation. Facing life without diving, he became depressed and wondered if this was the end of his diving. “But before the accident I had planned a trip to the Andaman Islands, and when the time came, I was healthy enough to go for it,” Allen said. “Even though I was basically a walking zombie and very tentative, I made it through the trip. It restored my confidence to the point where I felt I could continue with my life’s work.”

Considering the expansive area that Reef Fishes of the East Indies covers, it’s hard to imagine anyone, even Allen, surveying every fish on every reef. This is where Allen’s coral fish diversity index (CDFI) comes in. The CDFI is a method he devised for obtaining survey results by estimating the numbers of conspicuous indicator species. Completing CDFIs involves copious time underwater, and while Allen, a longtime DAN Member, strives to dive safely, he has had a few close calls, including being caught underwater during a tsunami in the Indian Ocean. Allen’s commitment pays off for divers and conservation organizations that use his surveys to determine the areas where protection matters most.

Divers have made his surveys easier, Allen said, especially at sites that have been heavily visited since he originally surveyed them. A perfect example is his recent dive at Cape Kri in Raja Ampat. Almost a decade ago, well before it became one of Raja Ampat’s most popular sites, Allen counted 327 fish species on Kri. When he returned few months ago, the change amazed him. “It was incredible how in just 10 years the fish had become accustomed to divers. I didn’t have to look for fish, they found me, and the survey was the highest species count I’ve ever tallied on one dive — 374 distinct species in a 90-minute dive.”

What’s the most unusual fish he’s ever found? “That would have to be a brackish-water relative of the silverside, which I found in the marine lakes near Sangalakki, a small island off Indonesian Borneo,” Allen said. “The male has a penis coiled on the side of its head.” And the female? The ultimate fish geek says he doesn’t know, but he sure would like to see the photos if anyone ever catches them in the act.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2012