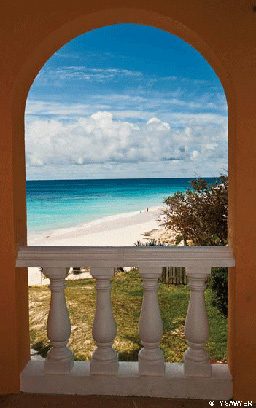

Bermuda has always been a beautiful conundrum. Its lawns and streets are among the most manicured on the planet. And, if such a thing is possible, its people have attained a level of civility that exceeds even the tidiness of the island. High tea comes each day with a punctuality the Swiss would applaud and with a traditional savoir faire and grace that could shame the rudeness from a schoolyard bully. As Mark Twain once said, “The deep peace and quiet of the country sink into one’s body and bones and give his conscience a rest.”

Yet there is disorder offshore. Well disguised as a jeweled garland that circles the island like a gem-studded necklace is a coral reef. On calm days, of which there are many, the coral bastion that protects the well-tended gardens and banks and shops looks like it could have been hijacked from a Disney exhibit. Wonderfully blue water wraps around delicate hard corals as sea rods and sea fans sway gently in the slight swell. And beyond lies a vast, wide-open sea of deep azure.

But there are days when viscous clouds gather in unruly crowds and the seas become contrary and roil and froth. The winds blow mercilessly; the sea and sky turn dark, and that lovely garland shows its thorns. Ships seeking refuge from the merciless sea take aim at Bermuda’s calm bays, invitingly fringed with placid pink sand and palms. In the past 400 seafaring years, the battlements that lay hidden just beneath churning water have cleaved the hearts out of hundreds of unlucky or unknowing vessels, all within swimming distance of shore.

The coral ring has shown no cultural bias, eviscerating and sinking British, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese and even local ships as if driven by a primordial hunger for destruction. Like a crazed serial killer, the sea has kept its prizes, embedded in pieces amid the sand and coral. Cannons, Aztec gold, gems, dinnerware, rudders, boilers, paddlewheels, pilothouses, anchors and ballast stones have all become part of the mosaic of Bermuda’s wreck-haunted sea. All are reminders that man’s presence in the world is ephemeral, small and easily extinguished. And all are reminders that Bermuda sits at a seafaring crossroads. Life on this tiny and strategic rock in the Atlantic is subject to the whims of the sea, and it has been that way since the first settlers were tossed upon its shores.

The Sea Venture

Bermuda was superstitiously avoided as the “Isle of Devils” until a group of English settlers heading for Virginia aboard the Sea Venture was shipwrecked in 1609, becoming the island’s first permanent residents. One look at the vast array of artifacts from 16th– and 17th-century shipwrecks on display at the Bermuda Maritime Museum tells how frequently the tale of the Sea Venture has been repeated. It is a tale that has lured me and thousands of other shipwreck enthusiasts to this refined realm over the years.

A Life’s Fascination

The first time I sailed into Bermuda I was in the U.S. Navy, crossing the Atlantic in a sailing race. We limped in, beaten by a sudden and frightening storm, the sails of our 48-foot sloop in tatters and our rudder inoperable. Passing over hundreds of years of shipwrecks, we were a prayer away from joining them. I wanted to hug the land when we finally pulled into the harbor, but the next morning I had forgiven the sea and began a relationship with the island that has spanned decades and eight return trips. I feel as if I’m just now beginning to understand this small island and to really know the stories behind Bermuda’s shipwrecks, which have come to reside in these waters for a variety of interesting reasons.

By Storm

My touchstone is the wreck I first dived in 1983, the 385-foot Pelinaion, which hit a reef in 1940 after the British blacked out St. David’s lighthouse during World War II. I’ve watched this wreck evolve over the years; storms have shifted it, and large grouper have come and gone. But the drama of this wreck, with its massive triple expansion engine and giant boilers, has never lost its appeal. As I dive it I imagine the calamity that brought it here — the dreadful crunching and high-pitched squealing of metal being ripped open by reef, the fish scattering from this catastrophic change to their world. Above the wails and howls of the wind, sailors’ voices prayed, shouted and screamed for help. I look at the boiler and can almost hear the unearthly hissing and the explosions of clouds of bubbles as heated metal and water suddenly met the coolness of the Atlantic. These are the stories that invade my mind as I explore each artificial reef; these tales are the heart of this wreck-ridden world. Only the magic of the sea could transform such moments of terror into tranquil ocean gardens.

By Treachery?

With more than 300 wrecks to dive, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by all the choices, but I love stories and usually decide based on a combination of remaining structure and intriguing history. The story of the 225-foot Mary Celestia, a side-paddlewheel steamer that sunk in 1864, is as intriguing as her ghostly remains.

During the U.S. Civil War, this steamer would slink through the seas as a blockade-runner for the Confederacy. A smuggler, the Mary Celestia toted food, guns, supplies and anything else the troops in the South needed, mostly under cover of darkness. On Sept. 13, 1864, with a full hold and a Bermudan pilot named John Virgin at the helm, the ship was headed out fast through the channel. When the crew pointed out some breakers in the path of the ship, the pilot insisted he knew the waters and then summarily slammed into the reef. Personally, I think it was done on purpose after some shadowy tavern deal made for insurance money or cargo salvage. A local and trusted pilot would surely have known the waters. But ships sink not only by storm, it seems, but also by scheme and perfidy.

Today, the intact paddlewheel sits at 55 feet, festooned with gorgonians and sea fans, becoming a vibrant mini-ecosystem. Its skeletal remains resemble a spider’s web lacing the graves of shipwrecked sailors. The Mary Celestia wreck site includes an anchor, boilers and crowds of marine life that have found refuge in its remains. And its mystery makes for a good discussion at the local tavern over a famed Bermudan rum swizzle.

By Plan

With so many natural shipwrecks, why would they need to sink even more wrecks on the crowded seafloor? Shipwrecks that make their way to Davy Jones’ locker usually do so in pieces, and divers who come to Bermuda for the historical wrecks still like to explore something complete. Plus, it’s nice to be able to take photos of wrecks that nondiving friends can recognize as wrecks.

Bermuda’s newest artificially sunken wreck bears an iconic name in Bermudan history: Sea Venture. But unlike the epic tale of shipwrecked sailors on the Isle of Devils that inspired Shakespeare to write The Tempest, the most recent wreck to carry the moniker Sea Venture plied its seafaring life prosaically as an island ferry. I’m sure some interesting liaisons happened aboard the 75-foot Sea Venture, or some swarthy characters used her for transportation. Her adventures may be over, but divers’ adventures have just begun. Acquired by the local dive shops in a moment of cooperation among them, they cleaned and sunk the Sea Venture in about 50 feet of water near the Eastern Blue Cut in 2007. They left a bicycle strapped to her roof just in case passing divers are in need of a little undersea cardio. The wreck has just begun to acquire a coat of encrusting corals and resident marine life. It’s intact and easily penetrated. Engine rooms, interior cabins and the pilothouse are all accessible.

Two of Bermuda’s other intact and purposely sunk shipwrecks are the most popular Bermudan wreck, the Hermes, sunk in 1985, and perhaps the island’s best-kept wreck secret, the 171-foot King George, scuttled in 1930.

The Beautiful Beast

Although they’re mostly the second-class citizens of the Bermuda dive scene, the reefs that surround the island are wonderfully lush and intriguing, despite the carnage wrought by the shipwrecks. Giant purple sea fans, hard corals and soft sea rods dominate the seascape. Snapper, wrasse, parrotfish and now lionfish are abundant reef dwellers. My favorite cavern is Cathedral, which is usually filled with clouds of shimmery hatchetfish and often a fat, lazy grouper that likes to nap in the shadows.

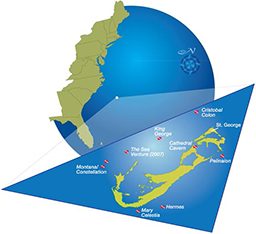

Although it seems exotic and far away, lots of divers from the East Coast escape to Bermuda for long weekends. It’s about 650 miles from Cape Hatteras, N.C. With 400 years worth of sunken ships and more than 300 of them accessible to recreational divers, you could vacation in Bermuda for a long time and never repeat a wreck. Few other places on the globe allow you to glide through so much maritime history firsthand. With a distinct air of sophistication, Bermuda is among the world’s most cosmopolitan dive destinations — it’s a cultivated world protected by a savage ring of ship-eating coral.

Top Wrecks

You can’t rent a car on Bermuda, so choose a dive shop close to the wrecks you want to dive, or switch sides of the island midtrip to dive wrecks on both sides (which I’d recommend). I usually start off on the eastern side of the island near St. George, designated as a World Heritage town by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The following wrecks are among the best.

Hermes — Sunk in 1985, this 165-foot ex-buoy tender sits upright on the sand next to a reef. A photographer’s dream, it’s the most popular wreck off Bermuda.

Mary Celestia — Sunk in 1864, this U.S. Civil War blockade-runner is 225 feet long and one of the island’s most visually intriguing wrecks. The intact paddlewheel has been turned into a miniature coral kingdom. The Mary Celestia is now in the news more than ever. Recent storms have uncovered portions of the wreck previously smothered in sand, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is partnering with the Custodian of Historic Wrecks and the Government of Bermuda to excavate and recover artifacts, including corked bottles of wine now known to exist on the wreck.

King George — Not many divers can find any mention of the 171-foot King George in their Bermuda logbook. For years it sat unmolested, and even now this 100-foot-deep wreck is dived only by special request — a request that’s definitely worth making.

Montana/Constellation — A two-for-one dive, the 236-foot Montana was wrecked in 1863, and the Constellation, a 192-foot, four-masted schooner, hit the reef in 1943. Both offer interesting coral-encrusted structures, including the Montana’s easily recognizable bow.

Pelinaion — This 385-foot Greek cargo ship split in two over the reef in 1940. The massive boilers (so big you can swim into them) and steam engine are must sees.

Cristobol Colon — The largest shipwreck in Bermuda, this 499-foot Spanish cruise liner sank in 1936 and now provides luxury accommodations for marine life.

Water Temperature and Visibility

Although you can dive year round, there’s definitely a best season to dive Bermuda for visibility. From December to April, when the water is in the mid-60s°F, the visibility soars to as much as 200 feet. As the water warms to as high as 82°F in the summer, algae blooms, and the visibility drops to 60-80 feet, sometimes less. The best times for visibility and warm water are June, October and November, when water temperatures are in the high 70s and visibility is around 100 feet.

Topside Diversions

Royal Navy dockyards — This includes the Bermuda Maritime Museum and the old Casemate Prison, which just opened to the public. The prison has some of the best views on the island.

Rum swizzle/dark and stormy — There’s a saying about the rum swizzle from the Swizzle Inn: “Swizzle in, swagger out.” Made strong with Bermuda’s Gosling Black Seal Rum, it may be best to call a taxi afterward. Locals prefer a dark and stormy, a concoction of Goslings and ginger beer that tastes best after tea and scones.

Pink sand beaches — Try Elbow Beach, Horseshoe Bay or Coco Reef, each of which offers wide expanses of Bermuda’s famous soft, pink sand.

Forts — For an island in the middle of nowhere, Bermuda was historically quite strategic. There are more than 90 forts on the island; St. Catherine Fort is one of the best.

Thomas Moore’s Jungle — The largest expanse of undeveloped land on Bermuda, the Walsingham Nature Reserve has a rarely visited swimming cave with crystal-clear water and some other caverns that make for exciting exploration.

High tea — There’s a saying: “Better to be deprived of food for three days than tea for one.” Every day between 3 and 5 p.m., Bermudans pause for tea, and around the island you’ll find plenty of places with traditional afternoon tea service.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2011