Whether your plans involve recreational or technical diving, hiring dive operators in remote locations requires you to consider several factors. Like every type of diving, every dive site calls for specialized training and preparation. This article uses Chuuk Lagoon, Micronesia, as an example of how divers should ensure their dive trips will be as safe as possible.

Travel-Related Concerns

After long flights to reach a remote destination, divers often arrive dehydrated and fatigued — two conditions that can contribute to dive incidents and decompression illness (DCI). A safe dive operation should begin by greeting divers at the airport with a bottle of water. Meanwhile, divers should take care to rehydrate on and after their flights and to rest before diving.

Informational Concerns

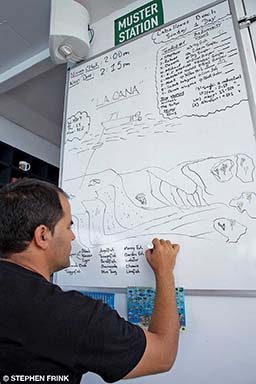

One of the most important responsibilities of the dive operator is to provide specialized briefings to discuss the schedule and explain dive protocols and environmental risk factors. Divers will learn about average visibility, depth, water temperatures and currents in addition to methods for navigating to and from wrecks. Every dive boat features a hang bar or weighted hang lines for divers to use while finishing decompression obligations and safety stops, and responsible dive operators will cover this information and provide extra gas from a regulator on deck for out-of-air or low-air situations. Reputable liveaboards will not only discuss this information during predive briefings but will also provide their protocols prior to booking. To choose the safest operators, do your homework beforehand and learn about their procedures.

Diving while fatigued can be especially dangerous, as divers must be able to maintain focus on buddy awareness, gear management, depth monitoring and buoyancy control. Tech diving is more complex with switching gases and tracking partial pressures of oxygen (PPO2). Reaching locations such as Chuuk Lagoon can require as many as four flights spanning several times zones over more than a day of travel, so travelers should consider arriving a day early to rest, rehydrate and recover before getting in the water. A well-rested dive group will run more safely and smoothly and in turn have more fun.

Before the dive, the liveaboard’s dive operations manager will ask dive teams about their plans and assign guides to the teams who want them. Each team should share what surface marker buoys they would deploy in emergency situations and how many tanks of nitrox or oxygen should be available via safety divers, if necessary. Prior to each dive, the operator will also inform each team of the location and availability of towlines and chase boats used to rescue overexerted or lost divers at the surface. Take responsibility for your safety by making sure both your team and the liveaboard crew have shared all requisite information before you get in the water.

Emergency Response

When planning a trip to a remote dive site, divers should research the availability of operational recompression chambers and quality health care. For example, Chuuk Lagoon has one privately owned functional chamber that is not always staffed because it relies on volunteers to operate it. As a result, dive operators in Chuuk Lagoon have protocols for dealing with suspected cases of decompression sickness (DCS): Patients must go to the local hospital for examination; if chamber treatment is prescribed, staff members are assembled to open the chamber. This issue is common for many isolated dive locales around the world.

As soon as dive operators suspect a case of DCS, they should contact Divers Alert Network® (DAN®) to open a case and get advice. If a local chamber is not operational, DAN initiates medical evacuation and takes over. For dive incidents in Chuuk Lagoon, air ambulances must fly several thousand miles from either the mainland United States or the Philippines to retrieve the patient, who will then be flown to Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines or wherever DAN deems the best treatment is available. It takes days to get there, which in severe DCS cases may result in serious disability. Thus, divers should dive conservatively to mitigate risk of severe DCS: Increase your safety margin within no-decompression limits, breathe nitrox, ascend slowly, and extend your safety stop. Medical evacuation is very expensive, which is one of the reasons dive operators recommend that every diver get DAN dive accident insurance.

Training and Preparation

Wreck diving, which is very popular in Chuuk Lagoon, often involves penetration diving — the deeper the wreck, the more complex the dive becomes. Divers should never dive beyond their training and abilities. When entering a wreck, divers with poor finning techniques can cause silt-outs (filling the water column with sediment), which can cause dangerously low visibility. While dive staff can offer tips and techniques to avoid this issue, it is paramount that divers ensure they receive all necessary training and certifications before leaving for their trip.

The dive team should decide what gear they will use, how many backup lights to bring, who will lead the dive and so on. Prudent divers will follow a dive guide for the complex portion of a penetration dive; local guides have years of experience and are likely to know the wrecks and dive sites far better than any visitor, so rely on their expertise.

Tech divers require additional dive equipment to complete complex dive plans. Open-circuit divers will use multiple tanks or sidemount tanks. Rebreather divers require special diluent, oxygen tanks and carbon dioxide absorbent. Most tech divers require decompression cylinders or bailout bottles to complete long decompression obligations. Traveling to remote destinations with all this extra gear can be an expensive and daunting task. To alleviate this issue, some operators have gear onsite, but providing supplies and equipment to tech divers becomes more difficult in remote dive locations such as Chuuk Lagoon, which must rely on preestablished supply lines to acquire and maintain inventories. It is up to divers to inquire about availability, and it is up to operators to ensure they can follow through.

Safety Equipment

Any liveaboard worth their reputation should have ample safety equipment on board specifically for diving and more generally for seagoing operations. Here are supplies dive operators should always have on hand:

- Communications devices: Safe boating and diving in remote locations require mobile phones, internet access when available and satellite phones. Should a diver get injured, the operator must be able to immediately contact emergency medical services and DAN to expedite care. Communications devices are also vital for monitoring weather conditions to allow time to prepare for severe weather.

- First-aid supplies: Dive operators should not only have first-aid kits, stretchers and automated external defibrillators (AEDs), but they should also frequently inventory and update medical supplies. Having items such as suture kits, medications and IV kits on hand can be helpful even if the crew is not medically trained to administer them: Doctors, nurses and emergency medical technicians are often guests on board who can provide advanced care until hospital physicians can take over. For this reason, it is beneficial to know prior to beginning a charter who on the passenger roster is medically trained.

- Oxygen: First aid for any suspected case of DCI includes oxygen administration. Every dive boat or liveaboard must have at least one complete oxygen unit on board, which will include oxygen cylinders with enough oxygen to get the patient to the next level of care along with continuous-flow and demand-valve regulators. Well-prepared operators might have multiple units available to care for more than one diver at a time.

When it comes to safety, every diver considering a trip to a remote dive destination should consider whether the risk is worth the reward. Take the time to research your options, and maintain high standards for not only your dive operators but also your own training, equipment, discipline and physical fitness. The best operations can provide the safest environment possible, but the individual diver and the smart decisions he or she makes will produce the safest and most fulfilling outcomes.

| © Alert Diver — Q4 2018 |