Diabetes is a disease that affects the endocrine system — the collection of glands that produce hormones, which regulate metabolism, growth and development, tissue function, sexual function, reproduction, sleep, mood and more. In the past the medical community advised against diving for people with diabetes, but today many diabetics are able to dive successfully and safely.

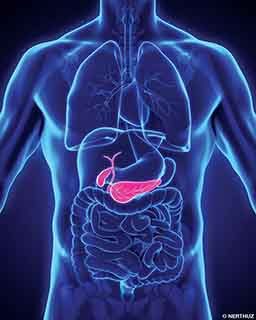

The main hazard of diabetes is its effect on the pancreas, the organ that produces insulin and glucagon, which are the hormones that balance and maintain your blood glucose (blood sugar). Approximately 415 million people worldwide suffer from diabetes, and by 2040 the number is estimated to rise to around 642 million.

Having diabetes means either your pancreas does not produce enough insulin or the cells of the body do not respond properly to the insulin produced. With type 1 diabetes, the pancreas fails to produce enough insulin, which leads to insulin dependency (the need for insulin injections). The cause of type 1 diabetes is currently unknown. Type 2 diabetes begins with insulin resistance, a condition in which cells fail to properly respond to insulin. This can also lead to insufficient insulin production. People can control type 2 diabetes by maintaining a healthy diet and taking oral medication. The most common causes of type 2 diabetes are an unhealthy lifestyle, excessive body weight and lack of exercise.

Medical experts historically advised against diving for people with diabetes because diabetics can experience potentially life-threatening conditions when suffering from high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) or dangerously low blood sugar (hypoglycemia).

Insulin (like physical exercise) lowers your blood sugar, and glucagon (along with foods that contain glucose) raises your blood sugar. People with diabetes may often experience overly high and low blood sugar levels, which puts them at a much higher risk of suffering an accident underwater. Developing hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia while underwater may lead to loss of consciousness and even death, especially when the illness is unstable or newly discovered.

Common risks, symptoms and effects of high and low blood sugar include the following:

- hyperglycemia (high blood sugar): extreme thirst, frequent urination, dry skin, hunger, blurred vision, nausea, drowsiness, slow-healing wounds and vomiting

- hypoglycemia (low blood sugar): trembling, fast heartbeat, sweating, dizziness, anxiousness, paleness, hunger, weakness/fatigue, headache and fainting

When people with diabetes experience any sign of such symptoms, they should immediately check their blood sugar using a blood glucose monitoring device. If blood glucose is low, they should eat or drink something with sugar or take glucose tablets; if blood glucose is high, they should take the appropriate medicine.

Symptoms and precautions are difficult, if not impossible, to identify and manage underwater. Due to the scope of potential problems diabetes can cause, people with diabetes face a greater risk when it comes to diving safely.

Even today some medical experts strongly disapprove of diving by people who have diabetes. Divers with diabetes, however, along with physicians and dive researchers have demonstrated that by taking the right precautions it is possible to pursue one’s passion for diving without jeopardizing one’s health and safety.

Before diving, people with diabetes should know their limits and always speak with professionals to get an objective assessment of their health status. No matter how well controlled one’s condition may be, people with diabetes cannot dive without restrictions. They must accept that the risks they face are higher — even if their diving skills are equal to or greater than those of nondiabetics. Having diabetes should not prevent people who are sufficiently healthy and capable from exploring the world, but they must always take the right safety precautions.

DAN Europe Diabetes Research

Results from research by DAN Europe suggest that to prevent worsening of hypoglycemia and to correctly interpret hypoglycemia-like symptoms while diving, divers with diabetes could benefit from real-time blood glucose (BG) monitoring during their dives. During one study of 26 dives in a hypberbaric chamber by diabetic divers, researchers noted no statistical differences among the BG measurements recorded every five minutes before, during and after dives.

This study, featuring the use of a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system in a waterproof case, was a perfect example of how technology can help people with diabetes increase their dive safety. A subcutaneous sensor monitored interstitial glycemia, and a display showed real-time blood glucose levels, allowing the divers to continuously check their BG.

Another DAN Europe research study found similar results, demonstrating through continuous monitoring that although BG levels declined progressively, diving did not impart a significant risk of hypoglycemia.

These DAN studies point to a potentially useful conclusion: A real-time CGM system used by diabetic divers while diving can provide immediate information on BG values and trend. This could mean both a significant increase in diving safety and enhanced knowledge of and interest in this specific field. These data could be valuable, considering that hypoglycemia-related problems during diving can be easily confused with other symptoms such as those that result from nitrogen narcosis or alternobaric vertigo (unequal pressure in the middle ears).

Natasha, a young diver with diabetes who took part in one study, had this comment about using the CGM system while diving:

“I’m used to regularly monitoring my blood glucose during the day; I’ve being doing this since I was a kid. However, being able to test it every five minutes while below the surface was just unbelievable. I finally felt safer while doing what I love most along with people I love: being underwater and enjoying marine life.“

For divers who do not suffer from any long-term complications, diving with diabetes is possible, provided they have regular medical checkups and keep their diabetes well controlled to minimize potential risks.

Recommendations for Diving with Diabetes

- Consult with a doctor who has expertise in diabetes and/or dive medicine before attempting to dive.

- Always wear a diabetes medical alert bracelet so fellow divers and rescuers are aware of your disease in case of an emergency.

- Always carry oral glucose with you, both on the surface and underwater. Make sure your buddy has some too and knows how and when to provide it to you.

- Have a glucagon injection available on the surface in case you lose consciousness.

- Eat food with slow-to-digest carbohydrates before you dive to promote a stable glucose level.

- Measure your blood glucose immediately before and after diving.

- Avoid depths greater than 100 feet. The risk of nitrogen narcosis increases at depths greater than 100 feet, and its symptoms can be confused with hypoglycemia.

- Avoid diving for longer than 60 minutes.

- Log your dives, and take note of your blood sugar levels for future reference.

- Do not dive in cold water, strong currents or conditions that demand strenuous activity.

- If you have type 1 diabetes, ensure your blood sugar is stable and no less than 150 mg/dL (8.3 mmol/L).

- Consider using a CGM system to check your BG in real time.

- Stay hydrated and healthy before, during and after diving.

- Remain relaxed, and enjoy the experience.

| © Alert Diver — Q1 2018 |