A day in the life of a garbage dump diver

The straps of the safety harness bite into my thighs when the tender attaches a steel cable from a 10-ton crane to a carabiner between my shoulder blades. The crane’s cable retracts, and my feet lose contact with the ground. My tender’s hand tightens around my ankle to keep me from spinning as the crane swings me around. Like a motionless marionette, I hang limply over a pitch-black, seemingly bottomless shaft. I breathe deeply to slow my heart rate. The team waits patiently for my command.

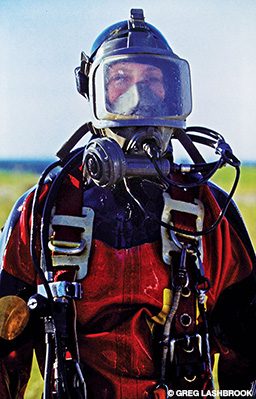

“Diver down,” I say. The microphone inside my full-face mask transmits my words to earpieces across the worksite. The crane’s engine burps out a cloud of diesel fumes. The cable uncoils, and my first dive into a garbage dump begins.

Kent County in Western Michigan faced a serious problem. The drainage system at the county landfill, which keeps toxic liquids from overflowing and contaminating the surrounding groundwater, got clogged. Unfortunately, the landfill’s master plan did not account for clogged drains.

The landfill is a 90-acre, 100-foot-deep hole lined with an impermeable geomembrane. An 8-inch perforated line lies across the width of the hole for drainage. Every 50 feet developers set on end a 4-foot concrete sewer pipe to function as a giant inverted funnel. As the dump filled with garbage, workers added additional sewer pipe sections to create vertical shafts from the bottom of the dump to the top.

The 8-inch lines on the bottom were clogged, and the county had no idea how to reach them. They needed help and encouraged anyone capable of unclogging a pipe buried under 100 feet of decomposing garbage to submit a bid.

Methane Divers

Wayne Brusate started his commercial diving business with one helmet and a communications system clamped to a 1-inch by 6-inch board in the back of his van. Ten years later Brusate answered Kent County’s call for help.

“When we got there, it was not what I expected,” Brusate said. “They were dumping garbage over here and covering it over there. And the smell…!”

Like a forgotten bag of lettuce in the back of the refrigerator, decomposing garbage turns into thick, black, smelly goo, which the waste management industry calls leachate.

The inside of a back-alley dumpster on a hot summer day is the underlying fragrance of leachate. The stench of rotting flesh and seafood mixes with the noxious fumes of household cleansers to create the unforgettable leachate-landfill aroma.

The smell assaults visitors before reaching the site. The human brain intuitively identifies the smell as toxic and slams the nostrils shut. The next breath passes over the tongue and burns the taste buds. The urge to skip-breathe is overwhelming.

Brusate said leachate was not the biggest issue. Methane was of much greater concern. The vertical shafts contained hydrogen sulfide and methane, which can form in the absence of oxygen but can ignite in the right mixture with oxygen.

“We lit a couple of shafts on fire to test the equipment,” Brusate said. They found that the lack of oxygen limited the fire to the top 10 feet, keeping the entire shaft from igniting. While the diver might be well below the flames, the umbilical unfortunately would be exposed.

Brusate spent months developing and testing all the protocols needed to safely drop a diver down a 10-story shaft filled with pure methane gas. It took another six months to convince the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) that it was safe from asphyxia risk.

Arnie Chickonoski is a 6-foot-tall, 300-pound walking teddy bear and a great guy to have at the end of a rope. He’s a professional firefighter and a seasoned member of Brusate’s crew.

“I couldn’t do it,” he said candidly about dump diving. One hour into his first dive, panic set in.

“I told Wayne, ‘Get me out! Get me out!’” Chickonoski said. While the topside crew jumped into emergency mode to expedite the process, Brusate calmly talked him through the panic.

“The next guy didn’t last much longer,” Chickonoski said. That diver succumbed to the heat: The dump’s interior temperature is a stifling, suffocating, heatstroke-inducing 102°F.

“I failed, and the next guy failed, so Wayne brings in a girl,” Chickonoski said. “And she did what we couldn’t.”

The Dive

The crane slowly lowers me into the shaft. The light dims.

I scan the concrete walls and look for loose material. A tiny piece of concrete falling 90 feet could cause a painful bruise. Anything bigger than a golf ball was potentially lethal.

I sparingly use a rubber mallet to knock off the loose bits and send them to the bottom ahead of me with the goal of not completely destabilizing the shaft’s walls. I slowly spin in a clockwise circle, and then counterclockwise, to keep my umbilical from becoming twisted.

Spin, scan, knock. Spin, scan. Spin, scan.

I keep my mind focused on the walls and not on my descent or what awaits me at the bottom. One of the other divers found 23 somewhat-intact bird carcasses.

The dump’s pungent aroma draws ring-billed gulls. From the birds’ perspective, the shaft’s rim appears to be a perfect place to roost. Tragically, the methane fumes asphyxiate the birds, causing them to lose consciousness and fall to their deaths.

Scan, spin. Knock, knock, spin.

Twenty minutes later, my feet touch a semisolid surface. Hot mush swallows my feet and oozes past my ankles. Thankfully, the bottom solidifies before the mush covers my knees.

“Stop. On bottom,” I tell the topside crew.

I peer through the darkness into the blackness. I’m used to zero-visibility conditions, so the lack of light isn’t an issue, but the heat is almost overwhelming.

“Slack,” I say. My feet sink another inch into the hot ooze as the harness releases its bite on my thighs. I ease down onto my knees before stopping the crane. I need enough slack in my lines to work, but too much and I risk entanglement.

The shaft is the size of an old-world telephone booth and feels as constricting as a middle coach seat in a row of strangers.

I reach my hand into the hot black muck. Redundant layers of rubber significantly reduce my sense of touch. The top is watery but quickly thickens to an oatmeal consistency. I’ll need to remove about 2 feet of muck to access the drainage line.

“Bucket down,” I say. Chickonoski gives the start command as he guides an empty five-gallon bucket down the shaft. He controls the bucket with an intricate set of hand signals to the crane operator. Both men wear headsets, but neither speaks.

Looking up, I see only a tiny dot of light in the far distance, reminiscent of an eye exam. I lean back against the hot concrete wall and try to stretch out my legs. A garden hose hangs beside me; I open the nozzle and place it against the nape of my neck where the thin latex of my protective drysuit allows the water to provide the cooling sensation my body craves.

The heat is slowing me down.

I’ve lost track of how many hours have passed or the number of buckets we’ve filled, but I’d managed to remove most of the leachate mush using a small plastic trowel. I am glad I did not find any identifiable bird bits.

Besides the incredible heat, the worst part of this job is sending the buckets back up. Chickonoski controls the crane cable, and a line tied to the bottom of the bucket allows me to guide it from below. Most buckets contain chunks of broken concrete. If the bucket snags and tips over, I’ve got nowhere to hide.

To guide it safely is a slow, tedious process. It’s been a slow, tedious and stressful day.

I enjoy the sound of the men’s camaraderie topside through the communications system; their voices are muffled as if coming from a television in another room. I hear bits of one conversation and pieces of another.

“Hey, Arnie,” I say into space.

“What’s up, Kath?” His chipper tone is incredibly soothing.

“Thinking about supper,” I reply.

“What’s the plan?” he asks. In a time-honored commercial diving tradition, the restaurant is always the main diver’s choice.

“Mexican?” I suggest.

“Sure, love me a wet burrito,” Chickonoski replies with a hearty laugh, adding, “Boss wants to know when we’ll be done.”

“Three buckets and I’m out,” I say.

“Roger,” he replies. The background noises muffle again as he pushes his microphone into the collar of his coveralls.

With my garden-hose water flowing out of the bottom of the shaft, I have finished today’s job. The topside crew works quickly to prepare for my ascent. While I wait, I distract myself by imagining I’m on a white-sand beach, and the searing heat is the welcome feel of the midday tropical sun.

I used to think the diver got to pick the restaurant as a result of having the hardest job. But that’s not true. Everyone on site worked hard. I had learned the reason had more to do with the fact that if anything goes wrong, the diver is the one most likely to die, making every meal potentially the last. It’s a sobering truth best left unspoken.

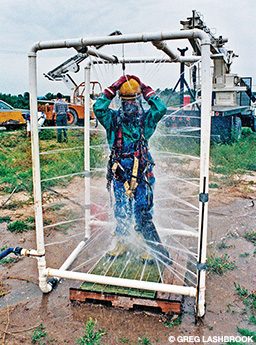

The crane lifts me clear of the shaft and drops me straight into a decontamination shower.

The shower is the best part of this job. The blessedly cold water removes the black layer of leachate covering my suit and cools my body. I linger in the spray as the crew secures the worksite; my only thoughts now are on where to go for dinner.

Author’s note: Following the system failures at the Kent County landfill, the waste management industry has changed landfill designs to incorporate long-term maintenance concerns.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2020