The diver was a 36-year-old female who had done four dives in the two months since her certification. She was physically fit and in good general health but reported having had intermittent difficulty equalizing during her certification dives.

The Dives

On a Saturday in June, the diver did a series of three dives to a maximum depth of 64 feet in a freshwater quarry. Her bottom times were within her computer’s no-decompression limits, and she had a minimum surface interval time of an hour between each dive. Her last dive of the day was to 45 feet for 45 minutes. She reported trouble equalizing during her first descent and increasing difficulty on subsequent descents. She did not complain of pain or any other significant symptoms, but she did report a feeling of “fullness” in her left ear. She didn’t dive for the next two days, and the sensation of fullness decreased but did not resolve completely.

After the two days the diver believed she would be able to equalize effectively despite the fullness, and she decided to dive again at the same location. Unfortunately, this time she found equalization difficult and uncomfortable as she descended. The discomfort persisted to her maximum depth of 55 feet. She continued to dive for about 20 minutes, but when she could no longer tolerate the discomfort she signaled her buddy, and they initiated their ascent. The approximately 20 feet, the discomfort had intensified to the point of pain. This distracting pain, combined with the diver’s inexperience, caused her failure to vent her BCD, and she made an uncontrolled ascent to the surface, during which the pain increased dramatically.

She had not done a safety stop, so she and her buddy attempted to descend to 15 feet to perform the missed stop. As they descended she was unable to equalize, and she made a forceful attempt at approximately 10 feet. She reported feeling and hearing a “pop,” and the pain in her ears became very sharp. The diver aborted the descent and managed to return safely to the surface, but she required assistance getting back to shore. Once ashore she was observed staggering and unable to walk without aid. She also became very nauseated and vomited several times. She found she could not tolerate lying flat or any movement of her head, both of which provoked nausea and vomiting. The diver’s buddy called emergency medical services (EMS), which arrived soon afterward and transported her to the local hospital.

The Diagnosis

Upon examining the diver, the doctor observed nystagmus (rapid involuntary eye movements) in addition to the acute nausea and vertigo she reported. Additionally, the diver complained of diminished hearing and a continued sensation of fullness in the left ear. Examination of the ears revealed slight redness of the right tympanic membrane (ear drum) with no other abnormalities. The left lymphatic membrane,

however, was markedly red and bulging, and an accumulation of fluid and blood was observed behind the membrane. These signs indicated an injury to the middle ear, but the diver’s symptoms indicated something more serious. The evaluating physician contacted DAN® for consultation.

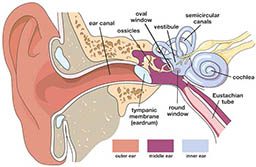

Based on the diver’s difficulty equalizing, her relatively conservative dive profiles and her forceful equalization attempt, some type of ear barotrauma was the most likely explanation of her symptoms. The severity of the symptoms seemed to indicate inner-ear barotrauma in addition to that of the middle ear. Inner-ear barotrauma means a perforation of either the round or oval window, the two membranes of the inner ear. This injury is usually treated with bed rest with the head elevated, avoidance of lifting or straining, stool softeners (to further minimize straining) and medication to relieve the nausea. The purpose of these therapies is to give the perforated membrane a chance to heal, and most individuals recover without complications or other interventions, as this diver did.

Discussion

Middle-ear barotrauma is the most common injury resulting from diving. It is a consequence of inadequate pressure equilibration between the middle ear and the ambient pressure of the external environment. During descent the Eustachian tube, which is normally closed, may fail to open if the diver does not make effective attempts to equalize or if congestion is present. Failure of the Eustachian tube to open can create negative pressure within the middle ear, which further closes the Eustachian tube and may draw fluid and blood from the surrounding soft tissues into the middle ear space. All of these factors can make subsequent efforts to equalize more difficult. Symptoms of middle-ear barotrauma include sensations of fluid or fullness in the ears, muffled hearing, mild tinnitus, dizziness and mild to moderate vertigo.

Early in our dive training we are taught we should never dive with congestion, a head cold or allergy symptoms, as these can interfere with equalization. Unresolved symptoms of middle-ear barotrauma — even mild ones — should also be considered reasons to suspend diving. The fluid, inflammation and closed Eustachian tubes will complicate equalization and place divers at increased risk for more serious injuries such as inner-ear barotrauma. Sudden pressure changes due to rapid ascents, rapid descents or forceful equalizations further elevate this risk.

Remember, if you encounter any equalization difficulty, stop descending, ascend a few feet and attempt to equalize again. If you cannot equalize, do not make a forceful attempt; abort the dive instead. Neither middle- nor inner-ear injuries are inherently life threatening, but nausea, vomiting and especially vertigo while submerged can place a diver at great risk and may even be fatal. Don’t be complacent when it comes to equalization, and don’t ignore ear discomfort while diving. Despite expenses paid or plans made, our hearing and lives are much more valuable. By discontinuing diving as soon as symptoms appear and staying out of the water until they resolve completely, divers can avoid increasingly serious injuries and prolonged recovery times.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2011