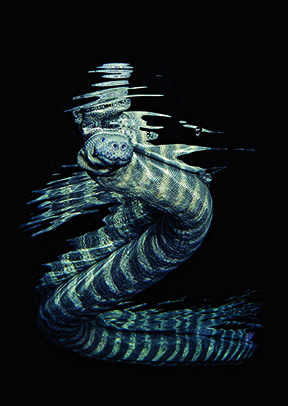

I FIRST MET SCOTT “GUTSY” TUASON at a Diving Equipment and Marketing Association (DEMA) trade show in 2016. “You need to see his blackwater work. You’ll be blown away,” Marc Bauman of Sam’s Tours said before introducing us. Tuason had just published Blackwater / Open Blue. As we sat in the Sam’s Tours booth, I thumbed through the book’s pages amid the distractions of a trade show. I was indeed blown away and later was able to give the photos and captions the slower pace and appreciation that a fine coffee-table book deserves. The book features blackwater macro photography and pelagic encounters with whales and sharks (hence the “open blue” appellation), but blackwater photography has been Tuason’s singular focus for quite some time.

We connected on Instagram, and I became more familiar with his vision’s excellence and eclectic nature with each photo. His macro photography — not just blackwater but also general coral reef minutiae — surprised me the most. So much of macro photography is reminiscent of a documentary, yet Tuason manages to infuse each image with artistic execution through his use of composition and light. Here is a glimpse of the man behind the photos.

To attain such a level of excellence shows a commitment to underwater photography as a lifestyle. How did you come to that point in your life?

I think my epiphany came in the 1980s from seeing the work that David Doubilet was doing in National Geographic, what you were doing in Skin Diver magazine, and the groundbreaking work by Chris Newbert in his book Within a Rainbowed Sea. By then I had a Nikonos V and a 35mm lens, but I wasn’t getting photos like those I saw on your pages. Wide-angle shots were especially hard for me to figure out. Using a 35mm lens meant I had to get farther away if I wanted to shoot something large. I didn’t know about water’s density compared to air and the blue cast subjects have at more than about 4 feet (1.2 meters) away, so I kept shooting from 15 feet (4.6 meters) and coming home with blue and poorly focused photos. Then I figured out the secret sauce. You all had the 15mm lens for your Nikonos cameras and could capture large subjects from a short distance. It seems so obvious now, but it was a revelation then.

How did you get to that point? Were you already involved in photography, or were you a diver first?

For that, we need to go back to my time as a child in Australia and then the Philippines. My mom is Australian, my dad is Filipino, and they met as students in Australia. We lived in Australia for a while, but I was too young for that to be formative for me in terms of diving. Once we moved to Manila, I was only 75 miles (121 kilometers) from Anilao. This was 1976, and I was just 8 years old, but we often went to Anilao. I snorkeled until I was about 10. My dad saw me tagging around in the shallow waters above him while he dived and finally said, “Here’s a regulator; follow me.” By 1980 I’d done my junior open-water course, and by 1985 I had my advanced certification.

Anilao remained a weekend getaway for my dad and me. By 1979 I had evolved from finishing whatever air was left in my dad’s bottle to finally having my own gear. But I think the real game changer came when a Spanish professional photographer, who then-president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos had commissioned to do a coffee-table book on our country’s visual wonders, hired my dad and Eduardo Cu Unjieng as dive guides. The team booked a three-week liveaboard dive trip to visit all the Philippine dive hotspots, which divers from North America travel around the world to visit. It was like a backyard to us, even though it was all new to me at the time. I had a 50-cubic-foot (1.4-cubic-meter) tank, a horse collar buoyancy compensator, and my own regulator, and I was keen to take it all in.

What about underwater photography? Was your dad a photo enthusiast too?

He was. He had a Nikonos III and would try to save a few frames for me to shoot at the end of a dive. I would hoard those frames until I saw something meaningful, and then I would shoot. That instilled good discipline that is with me even all these years later. For my 16th birthday I got my dream kit: a Nikonos V with a 35mm lens and an SB103 strobe. I took that kit with me when I went to the University of Tampa in Florida and enrolled in their marine biology program.

I’m not sure that I was passionate about marine biology, but it allowed me to dive. I soon figured out there was more to the program than diving, and most people who had a career in that field didn’t dive much. By then I was getting into photography and took a fine art photo class from Lew Harris, who inspired me and remains a dear friend. They had only two classes, an introductory class and “special problems,” so I took the same problems class every semester for two years, always trying to shoot a better photo or do a better job with it in the darkroom.

Eventually, I got a bachelor’s degree in economics, which I didn’t need for my first jobs after college: teaching tennis and cleaning yacht hulls. I also worked in a framing shop to earn money, but in the end my dad told me what I already knew: “You aren’t American, you are in jeopardy of overstaying your visa, and you need to come home.”

What did going home mean to you as a young college graduate with an economics degree?

It meant going to work in the family business. We had been a firearms manufacturer for 40 years, and I ran the wholesale side. I admit now that I had no interest in the business. Getting time off was hard, and all I wanted to do was be away from work to dive and take pictures. I managed to carve out a branch of the business that better suited me. My idea was to create a retail space to sell underwater camera equipment and gear for golf, tennis, squash, and diving in addition to firearms.

There was a photo print shop established in 1905 called Squires Bingham Photo Print, and they mostly created picture postcards. By the 1930s it had expanded to include sporting goods. My grandfather bought the business in 1941, shortly before the Japanese invaded the Philippines. I always found it interesting that the family business had its roots in photography before growing into our sporting goods store, Squires Sports Philippines. It is now my business, and while we sell dive gear, we aren’t a dive shop. We don’t do rentals or air fills, but we do have high-end retail. We also do dive travel, and I get to lead the tours. Before the pandemic, some of our more popular trips were to Tubbataha, Cocos, Socorro, Tonga, and Norway, where we focused on orcas. I will be back to Tubbataha soon, and it’s a good feeling to know our travel business is getting active again.

Do you still get to dive Anilao much since it’s close to your home in Manila? I see so much amazing blackwater work from there, and I heard you started it in the Philippines. Is that true?

I still dive Anilao on weekends whenever I can. It never gets old for me. As for blackwater, I went to Hawaiʻi for a wedding in 2012 and did the famous manta night dive in Kona. The local dive shop offered a second night dive on the manta trip to do a blackwater drift. I was in awe of the creatures we were seeing, but it also occurred to me that I could do this in other places. When I returned to the Philippines I tried the same protocols, but not without resistance. No one wanted to take me out on their boat late at night to drift along in deep water and shoot tiny things some people couldn’t even see. But I persevered, and I think you could safely say I started blackwater diving in Southeast Asia.

How long did it take you to amass the work that you published in Blackwater / Open Blue?

It was about three years of shooting steadily with that theme. I knew it would get to be a massive photo niche, and I wanted to be the first to do a book. The identifications were tough. I first contacted Jerry Allen, one of the premier fish identification guys. He helped when he could, but the animals were so obscure and new to being photographed in the wild that he sent me to other experts such as a jellyfish specialist or a cephalopod guru.

What is your primary emphasis in underwater photography today, and where do you want to see your photos published?

I think books will always be my thing. My books on Anilao and Bahura are Philippines portfolio books, and I’ve collaborated with others on books about seahorses, dolphins, Philippine coral reefs, and some topside subjects, like one I shot for the Manila Golf and Country Club. I’ve done 11 books so far, and I have ideas for several more that I’m currently working on. Magazine articles are not for me; the pace is too fast, and I can’t deal with the whole writing-on-a-deadline routine. I like to let the ideas germinate more slowly and shoot to a theme.

Explore More

See more of Gutsy Tuason’s work in a bonus photo gallery and in this video.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2022