In the spring of 2010, two members of the DAN® Medicine and Education departments traveled to Honduras to study harvesting divers in the hope of identifying ways to reduce the daily risks the divers take. Miskito Indians bypass safe diving limits every day to reap lobsters – locally referred to as red gold – from Honduran seas. They do it to make a living, but they pay a price that often costs them their quality of life, if not life itself.

More than 2,000 men are currently members of an unfortunate fraternity, the disabled divers in the La Moskitia region of Honduras. Their afflictions range from a limp to a chronic inability to stand or walk, all brought on by decompression sickness (DCS). But they are the lucky ones; they are alive. Reliable census numbers for this remote region do not exist, but an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 Miskito Indians live there. Of those, 5,000 to 10,000 of them work as divers.

La Moskita

To understand why anyone would willingly put himself at such great risk, it’s important to have a geographical and cultural overview of his surroundings. Puerto Lempira is the departmental capital of Gracias a Dios (meaning “Thanks to God”) in Honduras; it’s essentially the capital of La Moskitia. It is accessible only by water or air. There are no paved roads in the town, and the airport is a dirt strip with open-air shacks to serve as the terminal. Houses in Puerto Lempira and the surrounding villages are poorly insulated and often windowless, yet this is a malaria-prone area. Stilts raise homes off the ground to protect them from flooding and storm surge. Few have electrical service, running water or sanitation. Garbage litters the streets and the shorelines.

Waterways are the easiest and most common routes for travel as roads are inconsistent and rutted. There are some boats with outboard engines available, but just as often you see dugout canoes with men and women rowing from one area to another. There is little commerce of any kind, so men do what they have to do to feed their families.

In the case of those who harvest lobster, they dive.

The Dives

Miskito Indians dive for spiny lobster and conch in the fishing banks off of Honduras between the Bay Islands and the remote Swan Islands.

A typical lobster dive trip lasts 18 days. Boats pick up divers in Puerto Lempira and travel two to three days to reach the fishing banks. Then they do what defies imagination: They dive for 12 straight days, making between eight and 12 dives each day to depths between 100 and 140 feet. Depending on the size of the dive boat, there are 40 to 60 divers on board, which means that a single dive boat can be responsible for up to 720 dives in a single day. For each diver, there is also a cayuquero, a teenage boy who rows the diver into position. Each team (diver and cayuquero) loads a cayuco (canoe) with four scuba cylinders and sets out to dive. The diver catches as many lobsters as he can, and when he runs out of air, he returns to the surface, immediately swaps tanks and returns to the bottom. After the diver has gone through all four tanks, the team returns to the dive boat for another four tanks, drops off their catch and returns to fishing.

The divers have little or no training and only crude dive equipment; their “kit” typically consists of only a harness to hold the tank in place, a regulator, fins and a mask. They generally are not provided any sort of buoyancy compensator device, nor are they given depth or pressure gauges. Dive computers are nonexistent.

The Divers

While offshore, the divers live in squalid conditions; quarters are close and unsanitary. Depending on the boat, they may have nowhere to sleep except on deck. There are no toilets, and fresh water for drinking and bathing is limited.

The men are young, ranging in age from 20 to 40 years old. The divers realize there is a connection between the diving they do and the injuries they receive, but they feel they have to make these dives to provide for their families and continue working. They accept the risk. They pay the price.

All to earn the equivalent of about $30 US per day.

The Symptoms

DCS is commonly divided into two categories: Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1 encompasses pain-only symptoms, while Type 2 DCS includes any neurological issue such as loss of feeling, paresthesia or loss of strength.

According to DAN accident statistics, the most common DCS symptoms present in recreational divers are pain, numbness and tingling. Miskito Indian divers typically acknowledge a problem only when their legs become severely weak, they become paralyzed or have trouble urinating. Lesser symptoms are generally ignored or masked with drug use, including marijuana and cocaine.

Dr. Elmer Mejia has been treating Miskito Indian divers for nearly 20 years. He began as a medic at the hyperbaric chamber on Roatan, eventually working his way through medical school on a scholarship from the Episcopal Church. According to him, when paralysis occurs, it is typically around the seventh or eighth tank of the day, and while it often happens after several days of diving, there is no consistent “day” on which it occurs.

Injured divers often decline hyperbaric treatment in La Cieba, Honduras, choosing instead to return home to La Moskitia. The divers are reluctant to receive treatment; the combination of frightening symptoms, strange surroundings and the unusual (by their standard) treatment environment are often overwhelming to them.

Yet another, perhaps more significant factor comes into play as well. Some boat owners will pay as much as 25,000 lempira (approximately $1,320 US) to a diver who has become paralyzed. Divers may opt to discontinue treatment, believing they won’t receive as much compensation if they are healed. It’s hard to comprehend, but bent and crippled may be more financially rewarding than able-bodied and diving.

Sobering Consequences

When divers who opt for medical care stop making progress in the chamber, Mejia will halt further treatments. “If they still can’t urinate on their own, though, they have a much shorter life expectancy when they return home,” Mejia says. “They typically die from a urinary infection in two to three years.” Divers who return to La Moskitia able to urinate on their own have a much longer life expectancy, but they still have to live with the struggles of their disability in a very difficult environment.

Benediciones (Blessings)

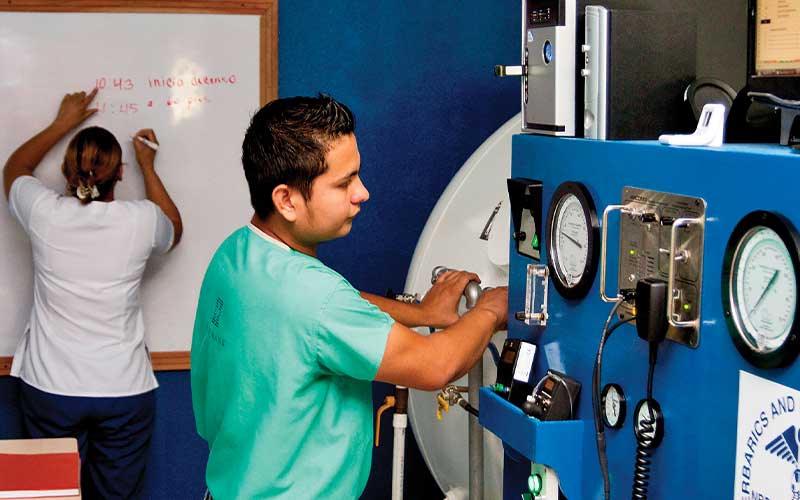

In August 2009, Mejia opened a small community clinic in La Ceiba, and in December 2009, he added a hyperbaric chamber, Clinica La Bendición (The Blessing). To make sure he had the best possible facility, Mejia used his own money, travelled to the United States, bought the chamber, and then he and his brother hauled it from Virginia to his home in La Ceiba.

In the first six months of 2010, Mejia treated 47 Miskito Indian divers with an average of seven treatments per diver; some required as few as four treatments, while others needed as many as 12. However, it was the slow season for harvesting diver injuries, because from March through June, the lobster season is closed. The closure is part of a government study to determine the feasibility of conch fishing, but at present only four boats are used to harvest conch, compared to the 42 boats dedicated to harvesting lobster.

According to Mejia, conch harvesting is actually more dangerous than lobster diving. The divers use a hammer to open the shell, actually removing the animal while on the bottom. They do it to reduce the weight they must transport back to the boat, but this additional workload increases the divers’ chances of injury.

“On our first trip to the region to meet with Dr. Mejia, we saw three bent divers in just three days, all of them with serious spinal cord hits,” said Dr. Matías Nochetto, DAN medical coordinator for Latin America. “Most of us will never see as many cases like that in our lifetime. Two more divers came the day after we left. As doctors, our primary goal is not to treat patients, but to prevent them from getting sick. But given the complicated reality the Miskito Indians live in, prevention is unbelievably hard to tackle. So at DAN we will not only try to educate these divers and the boat owners about safer diving techniques, we will also work with the medical community they rely on to make sure they receive appropriate and timely care. The overall Miskito divers’ lifestyle is shocking. What’s the human cost of lobster or conch?”

In addition to the lack of oxygen first aid available to divers and the long delays to treatment, Mejia also has to cope with bush medicine and misunderstandings. In response to the pain from the inability to urinate, the divers stop drinking. After several days in the heat, they become increasingly dehydrated. In other cases, in an effort to counteract numbness and tingling, divers are known to pour hot oil on their legs to try to “wake up their legs.” Mejia even saw a case in which the diver arrived at the chamber after being bathed in milk and garlic.

Mejia located his chamber close to the airport so he can get to divers who are brought in by chartered flight. This is one of the poorest areas of La Ceiba, so he also operates a community clinic, treating 30 to 40 patients a day for various medical complaints, regardless of whether they can pay. He often does the same for injured divers, because he has seen cases where boat owners refused to cover the cost of treating injuries sustained on their boat. Mejia doesn’t hesitate to assist; even when a diver cannot pay, he treats him because “es lo que se hay que hacer — it is the right thing to do.”

The DAN Plan

Through its Research, Education and Medicine departments, DAN is taking an active role in assisting harvesting divers in Honduras and other locations around the world. Through the Recompression Chamber Assistance Program (RCAP), DAN is supporting the hyperbaric chamber in La Ceiba with equipment and training to help ensure injured divers have access to appropriate medical care. DAN is also advising Mejia in his work with the divers and boat owners to find safer diving protocols. Through analysis of current diving profiles, historical treatment records and diving situations, the goal is to develop a safer approach to reduce the human toll.

DAN is also developing a process to train the divers to recognize the signs and symptoms of decompression sickness more readily and to understand the uses of emergency oxygen first aid. The hope is by teaching divers to breathe oxygen on the long boat rides back to shore, outcomes following chamber treatments will be significantly improved. It’s hard to imagine so many things we take for granted being so foreign to others, but until what we know becomes familiar to the harvest divers of La Moskitia, Mejia and DAN will be here for them.

Postscript

The government in Honduras recently elected to close lobster diving fisheries in June 2011. Knowing what’s coming, the boat owners will likely push the divers to pull more and more lobster from the sea in this last year of fishing, injuring an increasing number of divers. The boat owners are also threatening to sue the government for business losses, and the final decision remains up in the air.

However, the government did not close diving for conch. Most of the divers interviewed said they did not want to see lobster diving closed, at least until there was some other way to make a living. It remains to be seen how many lobster boats will transition to conch but in La Moskitia one thing is for sure: The options are few.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2010