Change: It’s inevitable, and it affects us every day. Technological advances continually transform phones, computers, tablets and even our toys (also known as scuba gear). The earliest innovations in dive gear occurred in the cave-diving community, and the advances made there eventually came to influence the equipment made by major manufacturers and used by sport divers everywhere.

In the beginning, dive gear was relatively straightforward, consisting of a single tank filled with air, a capillary or oil-filled depth gauge, a watch, a compass, a submersible pressure gauge and, for chilly dives, a wetsuit. Horse-collar buoyancy compensators (BCs) were common but were used more for surface flotation than for buoyancy control while diving. Dive times were computed using U.S. Navy tables, and sport divers for the most part avoided decompression diving. It all worked well for decades.

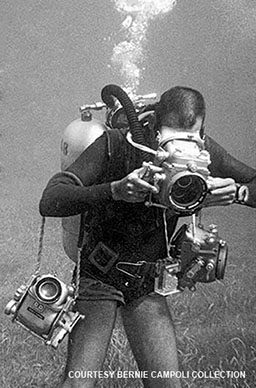

During the late ’70s and early ’80s, small changes in electronics began to precipitate technological advances. Dive lights were an early example of this as manufacturers adopted new battery technologies. Rechargeable nickel-cadmium (NiCad) batteries lasted longer than their predecessors. They also made for better strobes for photography, and flash bulbs quickly disappeared. As materials and manufacturing techniques improved, wetsuits and variable-volume drysuits became commonplace. The advent of the stabilizing jacket (by Scubapro) and power inflators changed diving techniques and made gear more comfortable. Like many new developments, however, these met with initial resistance, and curmudgeons grumbled about “push-button diving.”

Inspiration in Dark Places

The unique challenges of diving in caves made inventors out of many early cave divers. Originally, it was not possible to walk into a dive shop and purchase canister lights with long burn times. Reels were rudimentary, and many divers had to build their own or adapt other products (spear-gun reels were commonly used). Many divers made lights out of Lexan tubes and motorcycle batteries until manufacturers such as Ikelite began building dependable and long-lasting lighting systems.

In addition to new equipment, cave divers pioneered new methods and practices to enhance safety. One example is the rule of thirds of air management: Use one-third of your air supply to get in and one-third to get out, and keep one-third in reserve for backup. Standards such as three lights per diver were put in place, as were dedicated hand signals and training specific to the cave environment. Divers from many countries contributed to the learning curve, and these standards and protocols spread around the world — and this was before the Internet.

The frog kick was recognized as an efficient and stabilizing kick that was less prone to disturbing silt than the flutter kick (important for optimizing visibility and, thus, safety in caves). Open-water instructors had taught it as an alternative kick in the event the flutter kick was fatiguing. Today the frog kick is the preferred kick of divers in many environments. Underwater photographers quickly recognized that it helped them minimize their impact on the reef. The kick also allows for a reverse stroke, which can be very helpful in macro photography.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, companies such as Dive Rite, Halcyon and OMS were being formed to meet the needs of the cave divers. Buoyancy control is critical for safe cave diving, and back-inflation BCs were introduced. The backplate was born (originally by pounding a sheet of metal to shape on a log and cutting straps for holes) to allow divers to comfortably carry doubles. The use of a long hose (originally 5 feet long) for sharing air in restricted passages of caves was instituted. At first divers breathed from the shorter hose and stowed the long hose behind their head, but later they began using the long hose as the primary breathing source and securing the secondary regulator under their chin with a lanyard. Even as dedicated gear manufacturers came onto the scene, the community of divers continued to drive innovation.

Word spread as more divers engaged in cave diving and brought the methods and practices back to their hometowns. Nitrox and mixed gases were gradually introduced, and divers began to dive longer and deeper. Training agencies developed programs to teach advanced diving techniques, and Michael Menduno, publisher of AquaCorps magazine, introduced the term “technical diving.”

Dive computers, which came on the scene in 1983 with ORCA Industries’ EDGE, were beginning to make an impact, as was the increasing availability of gas mixes that could help optimize dive times. The option to switch to another gas to accelerate decompression had arrived. Generating dive tables using home computers was becoming the way technical divers planned dives. Cave divers figured out ways to carry these gases in streamlined configurations, and ideas were instantly shared and adopted by dive communities around the globe. Internet forums allowed communities of divers to adopt (or reject, as necessary) new ideas and techniques.

Innovation for Everyone

All these advances eventually worked their way into the sport diving community. Every manufacturer currently offers back-inflation BCs. Multigas computers are considered the norm, and recreational training agencies teach their use. On any given day, sport divers can be seen using innovations originally created by technical divers.

A recent development in our toys is the advent of sidemount diving, a configuration pioneered by cave divers in England. Adopted and modified by U.S. cave divers, this technique can now be seen in open-water diving. Sidemount diving was developed to help cave divers navigate small, tight environments. The cylinders are placed along the diver’s sides, and it was quickly discovered that there are a plethora of advantages for the open-water dive, such as improved trim, reduced strain on the diver’s back and easier kitting up while in the water. There are various sidemount rigs available to divers today — descendants of a custom, homemade kit. Once again, dive gear was modified by divers and then made available to the public by manufacturers.

These days the ultimate toy is the rebreather. Some divers have ventured into the realm of homemade rebreathers, but manufacturers are now light-years beyond the early versions. Designed by engineers and tested to perform under rigid standards, rebreathers are moving inexorably forward. Quiet, bubble-free diving, longer no-decompression times and more efficient use of gas are definite advantages.

Today’s electronics are truly yesterday’s science fiction. Although we don’t know exactly what the future will hold, divers will undoubtedly play the primary role in advancing diving technology once again. So keep diving, and keep thinking — creativity comes from using your imagination while you play with your toys.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2013