It was almost lunchtime when the phone rang. The familiar voice of a friend living in California echoed enthusiastically from across the continent. “Hey, Ned, I just got home from Fiji and wanted to let you know I was thinking about you.”

“How so?” I asked.

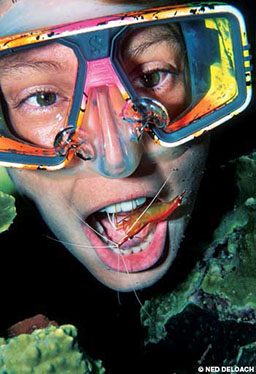

“We were on a dive trip on the liveabord Nai’a, and I saw your photograph of Cat Holloway with the shrimp in her mouth hanging in the passageway — you know, the one you took some 15 years ago, if recollections serve me. It’s still one of my favorites.”

The thoughtful call brought a rush of dusty memories. “Has it really been 15 years?” I wondered as I hung up the receiver and leaned back in my chair with the photograph dancing in my mind. But my thoughts quickly drifted from the image and settled on the unforgettable string of events that followed.

It all began sometime prior to my 1998 voyage aboard the Nai’a when Cat, who was the liveaboard’s cruise director at the time, learned to entice cleaning shrimp into her mouth. The two-inch crustaceans (in this case white-stripe cleaning shrimp) traditionally make their living feeding on the parasites that besiege reef fishes. To ease their infestations, “client” fish visit cleaning stations at intervals throughout the day. The stations are manned by certain species of shrimp and small fishes that are referred to collectively as cleaners. The cleaners, which tend to be immune to predation because of their invaluable services, regularly venture inside opened mouths where microscopic parasites, primarily larval isopods, congregate. In Cat’s case a predive meal of Vegemite and toast was employed to sweeten the deal.

For years Anna and I had enjoyed getting “manicures” from cleaner shrimp in the Caribbean, but we had never contemplated anything like Cat’s inspiring shrimp-in-the-mouth exploit. I just had to get a photograph. When the Nai’a moored near the home of her trained shrimp, Cat graciously agreed to model for a portrait with her hungry little friends.

Cat settled onto her knees in the sand next to a coral outcropping, removed her second stage and leaned forward with her lips drawn back and teeth bared. As her face neared the reef, a shrimp hopped aboard her approaching grin. After momentarily busying itself picking here and there it vanished inside Cat’s mouth. When the shrimp reappeared, a gentle puff sent it sailing back toward its roost. Cat looked up and, with a twinkle in her eyes, smiled and gave a sweet little shiver of delight.

When I saw Cat again the following year, the first words out of her mouth were about the shrimp. “You won’t believe it!” she trumpeted in her charming Australian accent. “I have the most extraordinary story about the shrimp. A guest named Ayesha — who is our dogs’ veterinarian in Fiji — was keen on getting her teeth cleaned. Everything was going perfectly; she settled her face in at the shrimp cave, and the regular pair of shrimp immediately began gum-dredging with their usual verve when out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of a coral trout making straight for us. Before we knew it the trout latched onto Ayesha’s lower lip and gave it a shake like a puppy tugging a rug. I helped Ayesha put her regulator back in her mouth, and we immediately headed up to the skiff. Isn’t that something? What in the world do you think got into that rascally trout?”

Still harboring an image of a lady with a fish hanging from her lip, I fumbled for an answer. “It wouldn’t have been after the cleaner … wow, I have no idea,” I admitted. “How’s the lady?”

“Oh, other than having a black, blue and swollen lip for a few days, the injury healed remarkably well,” Cat replied. “Fortunately, being a vet, she was accustomed to being bitten by animals.”

Several months passed before a cleaning encounter in Bonaire finally cast some light on the puzzling trout attack. I had just spent two dives unsuccessfully attempting to photograph a shrimp cleaning inside the gill opening of a cardinalfish, one of several dozen of the small, nocturnal fish taking refuge inside a coral head. My problem was too many fish. No sooner did I get a clear view than one of the skittish multitude blocked the scene.

Returning the following morning I found the cardinalfish clustered toward the back of the recess away from the cleaners, so I settled in for a wait. Having nothing better to do, I casually slipped my hand toward the shrimp — a mistake. A small grouper, known as a graysby, bolted for my outstretched fingers. I yanked my hand back just in the nick of time and hugged it tightly to my chest. The grouper turned, glared and then swam away, sending up a puff of sand in its wake before slipping inside the recess through a side passage, resting its head on an incline and opening its mouth wide. A nearby shrimp literally galloped across the sand and onto the waiting jaws. No sooner was the shrimp settled than the grouper sent it flying with a shake and swam away.

The message was loud and clear: This bad boy was, in no uncertain terms, asserting a proprietary claim to the cleaning station. A light bulb went on — graysby, coral trout, territory, bruised lip. I believe the run-in might have some bearing on the curious behavior of Cat’s “rascally” trout half a world away.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2013