According to legend, military combat swimming originated around 480 B.C. in a retaliatory operation against King Xerxes of Persia. Originally employed as salvage divers, Scyllias and his daughter, Cyana (or Hydna), found themselves hostage to Xerxes, who wished to retain their services during his wars against the Greeks. On a stormy night, the pair escaped by diving into the sea and breathing through hollow reeds. During their dive, they cut the mooring lines of Xerxes’ fleet, causing many of his ships to collide and be damaged or sunk in the stormy waters.

A century and a half later, during the siege of Tyre in 332 B.C., Alexander the Great’s military divers used an early prototype of a diving bell to help them remove obstructions from the water. The diving bells Alexander commissioned featured glass that allowed his combat swimmers to examine the seafloor. It is even rumored that Alexander himself used the diving bell to survey his men’s work.

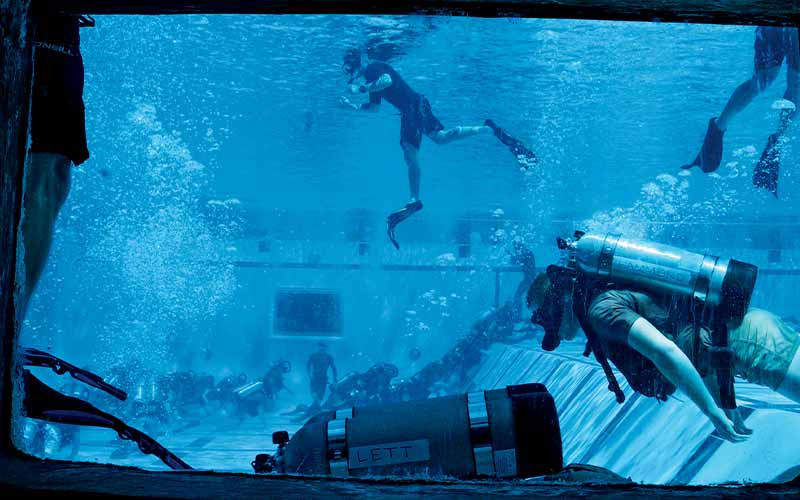

With increasingly sophisticated equipment, modern military divers are essential to many missions and campaigns. In addition to combat and demolition missions, military divers perform underwater reconnaissance, ordnance disposal, construction, ship maintenance, search and rescue, salvage operations, saturation diving and underwater engineering. Every branch of the U.S. military employs divers, and more than 40 nations have military diving operations today.

Military diving is an elite classification that entails risks and responsibilities unlike those of any other type of advanced diving. The contributions of military diving to both professional and recreational diving go far beyond the dive tables taught to new divers. In fact, development and innovation in military diving equipment often translates to recreational and technical diving practice.

Salvage Diving

The origins of modern military diving coincide with the spread of submarine technology in the early 20th century. Accidents and collisions marred the first several decades following the widespread deployment of submarines, so military diving’s focus at that time was on salvage.

In March 1915 the submarine USS F-4 sank in 300 feet of water during maneuvers off the coast of Honolulu, killing 21 sailors. During the mission to salvage the F-4 Chief Gunner George Stillson employed staged decompression, which allowed divers to examine the wreckage and work toward raising the boat. Further difficulties salvaging the vessel led Lt. Cmdr. Julius Furer to suggest the use of submersible lifting pontoons for the first time in any salvage mission.

One of the most intensive U.S. salvage operations began after the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. For two years following the attack, salvage divers worked diligently, logging nearly 20,000 hours underwater. Their labor and expertise allowed the military to place several battleships and numerous destroyers and supply ships back in service.

Alongside many of these salvage operations were rescue and recovery missions, which motivated the development of new diving equipment and provided opportunities to test them. As a response to the loss of the USS S-51 and the USS S-4 in the 1920s, for example, Charles B. Momsen and Allan Rockwell McCann developed the McCann-Erickson Rescue Chamber in 1930. Less than a decade later, the device assisted in the rescue of 33 submariners from the USS Squalus.

Momsen also designed his famed escape lung around the same time. The escape lung was a rudimentary rebreather consisting of a rubber bag and a canister of soda lime (to remove carbon dioxide). In October 1944, 13 submariners used the escape lung after a torpedo struck the USS Tang. Several men made it to the surface using the device, but others died in the attempt, perhaps because of lack of training in its use. Momsen’s technology contributed to the development of the Steinke hood and to the subsequent development by the British Navy of the Submarine Escape Immersion Equipment (SEIE), which is currently used by most NATO naval services.

Salvage diving in the modern world is a continually advancing discipline, following the modification and improvement of many devices for remotely operated deepwater situations. The military’s role in the advent of deepwater technologies is essential to the field’s growth.

Combat Diving

Combat diving requires specialized equipment and exposure to environmental elements absent from other military exercises. As an advanced diving technique, combat diving depends chiefly on closed-circuit breathing equipment, high-speed/low-profile vessels and finely tuned teamwork. Operating in hostile environments also requires expertise beyond what is standard in even the most highly trained elite combat branches.

In the United States, military experiments in combat diving go back as far as the Revolutionary War. After experiments with fellow Yale student Phineas Pratt to develop a timed detonator that would allow bombs to explode underwater, David Bushnell designed a miniature proto-submarine, the American Turtle, to allow its one-man crew to affix timed bombs to ship hulls. Unfortunately, the Turtle‘s drill was unable to penetrate the copper sheeting on the hulls of the British ships and failed to sink an enemy vessel. Other contemporary innovations included using water as ballast for submerging and raising submarines, employing breathing devices and attaching mines to the hulls of target ships.

During World War II, the Italian Navy solidified the importance of underwater attacks in modern warfare. The relative weakness of the Italian military in surface operations drove them to assemble a force of naval commandos who used closed-circuit oxygen systems to ride underwater on torpedoes modified for transportation. Using this method, Italy’s commando units successfully attacked two British battleships in Alexandria Harbor in 1941 and did significant damage at Gibraltar in 1942 and 1943.

The United States also saw significant advances in combat-diving technology during World War II. At that time Dr. Christian Lambertsen, now considered the “father of military combat diving,”1 was a medical student in the process of inventing the United States’ first closed-circuit oxygen rebreather system, the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit (LARU). Although closed-circuit systems already were in use by European military powers, Lambertsen’s system featured a more efficient design. Lambertsen’s professor at the University of Pennsylvania, a former British Army officer named Henry Bazett, saw the LARU’s potential for military application and in 1941 alerted the U.S. Navy’s Experimental Diving Unit and the British Admiralty, reporting that the “apparatus has advantages in lightness and freedom of movement in the water, making it adaptable either for use of underwater troops of the trouble-making type or for night-raiding enemy defenses.”2 The importance of this invention cannot be overstated, as it allowed divers to traverse long distances in stealth mode without releasing bubbles into the water.

During World War II Lambertsen contributed not only in equipment development but also as a military combat diver. In addition to training combat swimmers using an early version of the swimmer delivery vehicle (SDV), he was a true warrior, participating in missions to destroy and cripple enemy vessels. His work with the Office of Strategic Services (the forerunner to the Central Intelligence Agency) and with Special Operations Command during and after the war provided a practical and scientific foundation for the use of rebreathers in military operations today.

After the war many of the combat swimmer teams were disbanded, but Cmdr. Francis Douglas “Red Dog” Fane secured the ongoing relevance of the U.S. Navy’s Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs). In 1948 Fane invited Lambertsen to the Naval Amphibious Base, Little Creek, near Norfolk, Va., to train his two UDT squads in LARU equipment. In these early days many Navy commanders saw no use for the teams, but Fane recognized the military value of maintaining this combat element.

Fane played an enormous role in the introduction and improvement of many popular pieces of diving equipment. For example, he endorsed use of Jacques Cousteau’s Aqua-Lung and began training UDT squads at Little Creek on the open-circuit system in 1949. Later that year, Fane’s team used the Aqua-Lung to place explosives on a sunken wreck that was blocking the Norfolk shipping channel. Following that success, the Aqua-Lung saw combat use during the Korean War. Fane also acted as an early adopter of neoprene exposure suits, and his divers set the stage for widespread wetsuit use.

Interestingly, Fane also inspired the character of Mike Nelson in the popular television series Sea Hunt, which began its four-year run in 1958, inspiring children of the era to make dives into their swimming pools and bathtubs and dream of adventures in the sea. The show is largely responsible for turning “scuba” and “Aqua-Lung” into household words.

Today, the Navy SEALs are the world’s most recognized combat divers. Their legacy begins with the Office of Strategic Services during World War II and traces through the Korean War’s UDTs into the present day. In 1961 the Unconventional Activities Committee established SEAL units in the Pacific and Atlantic and recommend the acronym SEAL as a combination of “sea, air and land” to indicate “all-around, universal capability.”3 The establishment of two SEAL teams in early 1962 recognized the need to combine sea, air and land expertise for the purposes of conducting unconventional, counter-guerrilla and clandestine operations.

Through Lambertsen’s early influence and leadership, all branches of the military have been involved in combat diving. This year the U.S. Army Special Forces Underwater Operations School on Fleming Key near Key West, Fla., celebrated 50 years of dive combat training.

Fleet and Engineering Diving

In addition to combat and salvage diving, military diving requires tasks such as inspection, repair, underwater electronics installation, construction, torpedo recovery and harbor clearance. Recently, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers instated a dive team, which completed its first underwater missions in 2012. This team, called the Forward Response Dive and Survey Team, employs bottom SONAR surveys augmented by surface and underwater inspection of sea-bottom, seawall, pier and docking facilities. They couple the information gathered through structural surveys with diver observations to facilitate major repairs and harbor dredging. There are currently 15 Army installations with waterfront facilities that require inspection every four years.

From Navy dive tables to technological and technical innovations, military operations have contributed many significant scientific, medical and equipment advancements that have permeated commercial and recreational diving.

References

- Mark. Dr. Christian Lambertsen: 70 years of influence on the military dive community. The Official Homepage of the United States Army. Accessed: May 18, 2014.

- Vann RD. Lambertsen and O2: Beginnings of operational physiology. Undersea Hyperb. Med. Spring 2004; 31(1):21-31.

- SEAL History: The Story of Naval Special Warfare. Navy SEAL Museum. Accessed: May 20, 2014.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2014