I’ve heard it suggested that the golden age of underwater photography was in the 1980s. That notion rested on three factors:

- Dive gear, including computers, was reliable and sophisticated enough to easily travel with and perform well on location.

- Underwater camera gear was reasonably advanced. The Nikonos camera system had evolved to the point where extension tubes for macro photography and the legendary 15mm lens for wide-angle photography provided alternate perspectives to the original 35mm water contact lens. A variety of housing and strobe manufacturers supported the single-lens reflex film cameras of the day, which allowed for fisheye, macro-telephoto and even over/under imaging.

- New dive destinations were being developed throughout the Caribbean, Red Sea and Pacific. Water quality was stellar, coral formations were pristine, and fish were bountiful. Global warming, ocean acidification and plastic pollution had yet to percolate to our collective consciousness. The clues were there, but the effects not yet apparent.

I have a wall of 35mm slides from those days, all carefully catalogued by destination and chronologically arranged by time of visit. It might have been the sweet spot in time for our reefs, but these are not necessarily the best images of my career. Only rarely do I revisit these files to scan them and transform them to digital format for Alert Diver’s publishing workflow. Why? Because the digital images I began shooting in 2001 are better (and easier to locate in a carefully catalogued hard-drive archive).

In underwater photography, two events were most transformational in elevating image capture to the new heights of excellence we see today in the photos submitted to our annual Ocean Views contest: digital image capture and the internet.

Digital cameras became especially useful for underwater photographers — we were no longer limited to the 36 exposures offered by a roll of film. The capacity of a compact flash card allowed several hundred images per dive, and that increased capacity meant more photo ops per dive as well as the freedom to take chances and to experiment with lighting and composition. Instant image review was an extraordinarily powerful innovation, too; we no longer had to guess at the exposure, take the photo and wait sometimes two weeks for the processed slides to come back from Kodak. We saw the results in real time on an LCD screen on the back of the camera. We were either satisfied with the image, or (more likely) we tweaked things to optimize. Photographers got better faster, and the things they were able to capture became more diverse and exotic.

The internet brought with it a global underwater photo community, connected by social media and destination awareness. Suddenly we knew when the whale sharks would congregate off Isla Mujeres and what season was best for great white sharks at Guadalupe Island, Mexico. People shot, posted, discussed and widely shared their dive experiences. Divers had new destinations to visit for new imaging potential, and techniques that few had tried before, such as blackwater photography, became obsessions.

Ocean Views celebrates a new sweet spot in time for underwater photography. More than a thousand photographers from around the globe submitted more than 26,000 digital images to the annual Nature’s Best Photography Windland Smith Rice Awards competition, which are distilled into 10 separate natural history categories, including one dedicated to the beauty and diversity of ocean life. Narrowed again to the 17 images you see reproduced on the pages of this issue of Alert Diver and in Nature’s Best Photography magazine, several will also appear this fall on exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. Digital imaging made capture more efficient; the internet made the destination research easier. But in the end — whether in 1982 or 2018 — it is the eyes of the photographers and their ability to technically execute an underwater photo that elevates their pixels to the paper and ink you see in our 2018 Ocean Views gallery.

— Stephen Frink

Winning Image

Gray Whale

Magdalena Bay, Baja California Sur, Mexico

By Claudio Contreras Koob

Every winter gray whales embark on an enormous migration from the freezing waters of the Arctic to the mild waters of coastal lagoons in central Baja California, Mexico. I was there photographing the lagoons for Wildcoast, an organization that supports protecting the region’s wetlands, which ensures a safe haven for the breeding whales. I was fortunate to find this totally relaxed whale approaching our boat, which allowed me to carefully introduce my camera partially into the water to show his brilliant eye and smile.

(Canon EOS 5D Mark II, Sigma 15mm f/2.8 EX Diagonal Fisheye lens, 1/320 sec @ f/11, ISO 1600, handheld; claudiocontreras.com)

Highly Honored Images

Manta Ray

Mayotte Island, Mozambique Channel, Indian Ocean

By Gabriel Barathieu

I was face to face with this giant manta ray in the lagoon of Mayotte Island. I saw it arrive from a distance, shaving the sand like a fighter. It was a moment I could not miss. I took a deep breath and went down to sit at the bottom and face it without moving. It passed just above me, like a plane taking off. Magnificent!

(Canon EOS 5DS, 15mm f/2.8 fisheye lens, 1/640 sec @ f/11, ISO 400, Subal housing; underwater-landscape.com)

Sharpear Enope Squid

West Palm Beach, Florida

By Judy Townsend

I was looking for plankton to photograph at night while drifting at about 15 feet with the ocean floor about 500 feet below me when I saw this beautiful sharpear enope squid (Ancistrocheirus lesueurii). Photographing animals such as this one at night is challenging: We have to find them and get them in focus while they are swimming and feeding, all while we’re drifting with the current. Some animals, like this squid, are very small. Looking for animals on blackwater dives is like a treasure hunt; we never know what we will find.

(Nikon D7000, 60mm micro lens, 1/250 sec @ f/25, ISO 250, Inon Z-240 strobes (2), Bigblue focus lights (2), Nauticam housing; sfups.org/photo-galleries/judy-townsend)

Florida Manatee

Three Sisters Springs, Crystal River, Florida, USA

By Carol Grant

Is this manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) communing with the fish? Only he knows for sure. Manatees are masters at warming and resting despite environmental distractions. Both this manatee and the snapper treasure the warm outflow of the freshwater spring during the Florida winter. Natural spring warm-water winter resting sites have disappeared throughout much of the manatee’s range.

(Nikon D300, Tokina 10-17mm lens at 13mm, 1/80 sec @ f/9, ISO 640, Sea and Sea YS-110 strobes (2), Subal housing and 8-inch dome port; oceangrant.com)

Clark’s Anemonefish

Lembeh Strait, Sulawesi, Indonesia

By Pedro Carrillo

A juvenile clownfish hides in the mouth of its host, a beaded sand anemone. Host to seven different species of clownfish, this is the favorite anemone of the Clark’s anemonefish. Known as a nursery, it is often a temporary home for young clownfish on their journey to find a more suitable host anemone for adulthood. Its mesmerizing pattern beautifully frames the orange color of the contrasting tiny fish.

(Nikon D4, Nikon 70-180mm f/4.5-5.6 AF-D Micro-Nikkor lens at 78mm, 1/250 @ f/16, ISO 100, Seacam Seaflash 150D strobes (2), Seacam housing; instagram.com/pedrocarrillophoto)

Orca

Peninsula Valdés, Chubut, Argentina

By David “Baz” Jenkins

Orcas (Orcinus orca) arrived at Peninsula Valdés to hunt at the attack channel and were looking for young sea lion pups playing in the surf at the water’s edge. Orcas must wait for the right time to attack so they don’t get stuck on the beach. It’s a difficult skill to perform, and on this occasion one orca missed its target and got stuck. It had to thrash its body from side to side and propel with its tail until it finally made it safely back into the water.

(Canon EOS-1D X, Canon EF 400mm f/4 DO IS USM lens, 1/1250 sec @ f/10, ISO 400, handheld; trackerbaz.com)

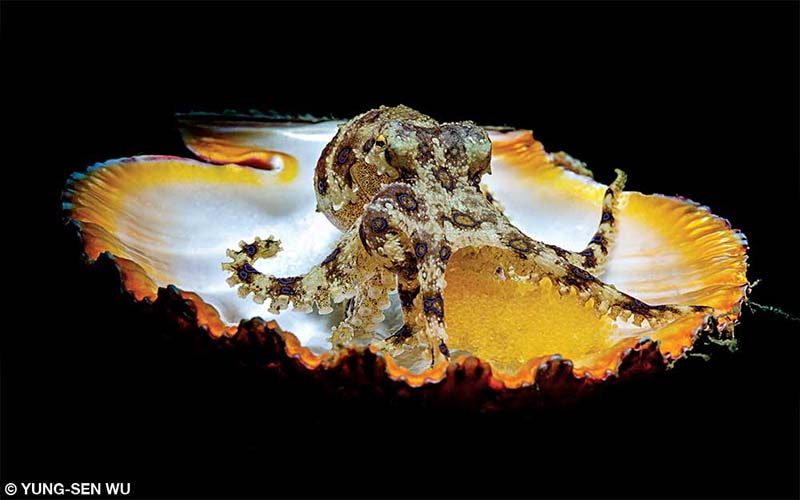

Blue-Ringed Octopus and Eggs

Lembeh Strait, Indonesia

By Yung-Sen Wu

At 89 feet (27 meters), in a crack between some rocks at the bottom of Lembeh Strait, a blue-ringed octopus was sucking in and blowing out some yellow stuff. I looked closely and saw that the yellow stuff was eggs — possibly those of a fish or a crustacean. According to Cephalopoda expert Wen Sung Chung, it’s possible that the blue-ringed octopus attacked a crustacean and carried away its eggs or the eggs were too sticky for it to get rid of.

(Canon EOS-1D X Mark II, Canon EF 100mm f/2.8L Macro IS USM lens, 1/250 sec @ f/20, ISO 640; 500px.com/hmap666)

Sand Tiger Shark and Baitball

Morehead City, North Carolina, USA

By Debbie Wallace

We descended into the waters off North Carolina atop the Caribsea wreck and encountered what initially appeared to be very low visibility. As we approached closer, however, we saw it was a massive baitball of scad. As we watched, several large female sand tiger sharks (Carcharias taurus) carefully and slowly entered and exited the baitball as if they were uninterested in the feeding opportunity. This young female was just beginning to enter with her own entourage in tow while being escorted by a large school of fish.

(Olympus OM-D EM-1 Mark II, Panasonic Lumix G Vario 7-14mm f/4 lens at 7mm, 1/125 sec @ f/4.5, ISO 250, Inon Z-240 strobes (2), Nauticam housing; debbiewallacephotography.com)

Freediver with Blue Maomao and Red Pigfish

Blue Maomao Arch, Poor Knight Islands, New Zealand

By Robert Marc Lehmann

The water was quite cold, and the current was very strong when I took this image while freediving, which makes it even harder to get everything right. I had to hold my breath as I was waiting at around 33 feet (10 meters), lying on the rocks so as not to disturb the swarm. The freediver came down through the thick layer of fishes with the daylight in the background. I like the little red pigfish trying to sneak into the blue swarm and the image.

(Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Sigma 15mm f/2.8 EX Fisheye lens, 1/40 sec @ f/6.3, ISO 1000, Subtronic strobes (2), UK-Germany housing; robertmarclehmann.com)

Tailspot Clingfish

St. Eustatius, Dutch Caribbean

By Barry B. Brown

Using a manned submersible, scientists from the Smithsonian Institution discovered this quarter-inch tailspot clingfish, Derilissus lombardii, living on a deep vertical wall at around 450 feet and brought it to an aquarium on board our research vessel. Photographing the clingfish was a challenge because of its tiny size and the motion of the ship. I’ve been shooting deep-sea creatures for the Smithsonian for many years and have found that every animal presents a different challenge. This clingfish was so tiny and moved so quickly that there was rarely time to compose a shot — like trying to photograph a feeding hummingbird.

(Nikon D810, 105mm f/2.8 lens, 1/160 sec @ f/32, ISO 200, Ikelite DS161 strobes (2), Ikelite housing, Manfrotto tripod with a pan/tilt quick-release head; coralreefphotos.com)

Humpback Whales

Ha’apai, Kingdom of Tonga

By Vanessa Mignon

Every year humpback whales migrate from Antarctica to the warm waters of Tonga to give birth. During that time it’s sometimes possible to swim with them. A gentle and quiet approach is essential — if you take your time, the whales might get used to your presence. On this day we were able to spend more than an hour with this pair. They would move slowly, always staying close to each other as if in a graceful underwater ballet. In this image, the pair is coming back to the surface together to breathe.

(Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L II USM lens at 16mm, 1/200 sec @ f/9, ISO 320, Nauticam housing; vanessamignon.com)

Crabeater Seals

Errera Channel, Antarctic Peninsula

By Cristobal Serrano

The lives of crabeater seals are inexorably linked to sea ice, which provides a place to rest, mate, give birth and raise their pups. They will likely have difficulty adapting to ice-free summers. Melting water is harmful to the ice sheets when it flows into cracks and refreezes. As temperatures continue to rise as a direct consequence of man-made global warming, the pace and extent of this damage will increase. In this image, 40 crabeater seals are densely packed onto a tiny ice floe, waiting for humans to take action on this issue.

(DJI Phantom 4 Pro Plus drone, 8.8-24mm f/2.8-f/11 lens at 8.8mm, 1/200 sec @ f/5.6, ISO 100, handheld; cristobalserrano.com)

Blanket Octopus

Janao Bay, Anilao, Batangas, Philippines

By Songda Cai

A colorful blanket octopus (Tremoctopus violaceus) drifts freely with its wings spread out wide. My interpretation for this shot is the title “Soar.” With its wings spread out over the black background, it’s as if this wonderful creature is soaring and gliding in outer space. The tiny critter was trying to appear larger than it really is, which resulted in this perfect shot.

(Nikon D850, Nikon AF Micro-Nikkor 60mm f/2.8D lens, 1/320 sec @ f/25, ISO 500, Seacam Seaflash 150D strobes (2), Scubalamp V6K Pro (4), Seacam housing; scubashooters.net/portfolio/cai.songda)

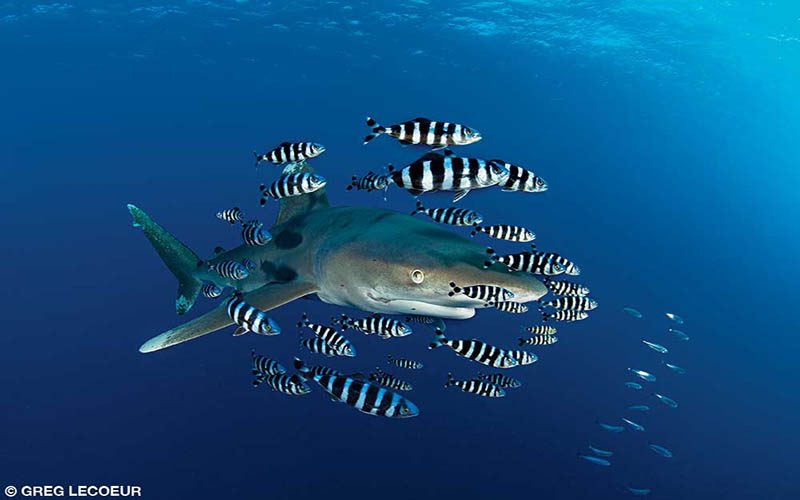

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

El Ikhwa (Brothers) Islands, Red Sea, Egypt

By Greg Lecoeur

In the Red Sea, oceanic whitetip sharks were victims of their bad reputations and were killed by humans some years ago. This apex predator, however, is important for the good health of the ocean and is slowly coming back. Accompanied by pilot fish, this inquisitive pelagic shark inspects everything that catches its attention and does not hesitate to come into contact with divers.

(Nikon D7200, Tokina 10-17mm f/3.5-4.5 fisheye lens at 10mm, 1/200 sec @ f/9, ISO 100, Ikelite DS160 strobes (2), Nauticam housing; greglecoeur.com)

Goby Eggs on Tunicate

Seraya, Bali, Indonesia

By Henley Spiers

A father goby carefully watches over his eggs on a tunicate that is about 2 inches (5 cm) long. Incubating and hatching of eggs are finely attuned to the rhythm of the ocean. This goby will try to time the eggs reaching maturity with the full moon, when the currents will be strongest and the eggs will have their greatest chance of being widely spread.

(Nikon D7200, 105mm f/2.8 lens, 1/320 sec @ f/22, ISO 100, Sea and Sea YS-D2 and Inon Z-240 strobes (2); Retra Light Shaping Device, 10Bar laser snoot, Nauticam housing; henleyspiers.com)

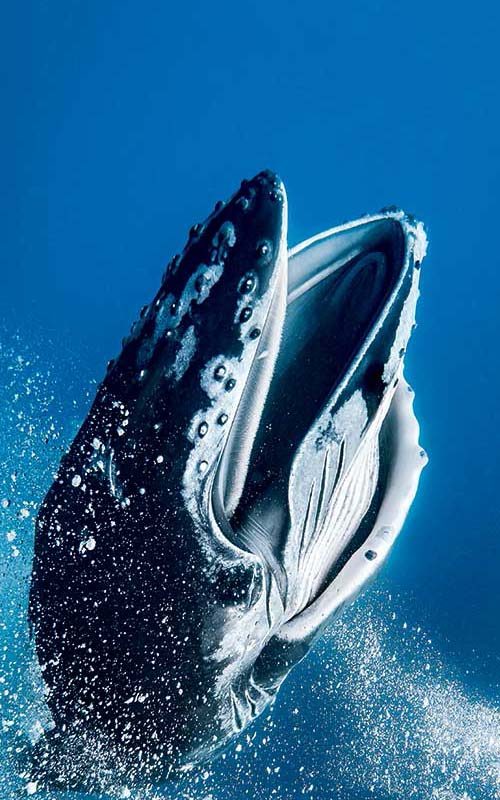

Humpback Whale Calf

Moorea, French Polynesia

By Ron Watkins

This young humpback whale calf is either playing in its mother’s bubbles as a game or learning how to bubble-net feed, which will be a key survival skill once it leaves the safe, warm waters of Moorea. Humpback whales feed only for the half year they are in the cold, rich waters of Southeast Alaska and Antarctica. It is truly an incredible experience to be in the presence of such large and graceful animals.

(Nikon D800, 16-35mm lens at 16mm, 1/320 sec @ f/16, ISO 160, Sea and Sea housing; ronwatkinsphotography.com)

Mediterranean Seahorses

Gulf of Rijeka, Croatia, northern Adriatic Sea

By Adriano Morettin

For a few weeks last summer I followed a beautiful (and cooperative) Mediterranean seahorse that often paused every few inches, allowing me to photograph him in various poses. One day he suddenly darted about 15 feet to stop near another, smaller seahorse of the same species, which I immediately understood to be female. He initiated a mating dance that lasted for several minutes, at which point the pair shot up from the bottom, danced briefly together and finally mated. I have been shooting underwater for more than two decades, but I had never before witnessed such a fantastic and rare event.

(Nikon D800E, 60mm f/2.8 micro lens, 1/250 sec @ f/22, ISO 100, Seacam Seaflash 150D strobe, Seacam housing; instagram.com/adrianomorettin/)

| © Alert Diver — Q3 2018 |