While most of us will never go to the extremes of a professional wildlife photographer like Paul Nicklen, all underwater photographers, at some point in their shooting life, will find themselves captivated by the unique subjects found only in temperate or cold water. Whether you’re shooting the white sharks of Guadalupe and South Australia, the wolf eels of British Columbia, the shipwrecks of Scapa Flow or the leopard seals in Antarctica, here are five pro tips for capturing better images in cold water.

Tip #1

Get adequate thermal protection.

It’s hard to take great images when your teeth are chattering, your fingers are frozen, and your only conscious thoughts are focused on getting somewhere warm. Any serious shooter working in cold conditions will embrace drysuit technology. One word of caution: Trying to master the intricacies of a new drysuit while concentrating on underwater photography is a recipe for trouble. I strongly advise photographers to get familiar with any new exposure protection and accessories before adding an underwater camera and strobes to the mix. Drysuit diving will require far more weight than light tropical wetsuits, and compensating for that weight at depth can be tricky at first. A little practice mastering your buoyancy now will pay off in safer dives and better photos later.

Finding the right gloves can be a challenge. Tropical gloves, which allow terrific maneuverability, will soon prove painful in cold water. Since any discomfort that shortens the dive will also decrease the efficiency of the photo outing, this is a tough compromise. I’ve tried the three-finger titanium mitts, and while they are very warm, they were clumsy when accessing small dials and buttons on my digital housing. The best solution I’ve found: dry gloves.

Tip #2

Adjust for color and clarity.

They don’t call the waters off British Columbia “The Emerald Sea” for no reason. The color of the cold water is often quite different than the bright cyan we find in the tropics.

Digital cameras have considerable latitude in terms of color temperatures used to record the image. Many have presets such as “cloudy day” (a good default for use in clear tropical waters) that adjust the white balance settings. Others have manual color temperature settings in degrees Kelvin. Here is a general guideline for approximate color temperatures in degrees Kelvin as recognized by digital cameras. Lower temperatures are at the red/yellow end of the color spectrum, with higher temperatures at the blue/green end.

- 2000 candlelight

- 3000 tungsten and halogen

- 3500 early morning and late afternoon sun

- 4200 fluorescent

- 5000 daylight and flash

- 6000 cloudy day

- 8000 shade

My preference when working in green water is to tweak the color balance somewhat lower than I might in tropical waters. For example, I typically shoot at 5700 degrees Kelvin in the clear blue of the Caribbean, but I like to go to 5200 degrees in greenish water. The goal is not to make the water look blue, but to tone down the excessive green cast. Remember, white balance is a global control, so adjusting for the color bias of the water column will also affect the daylight-balanced strobe light striking your subjects. Going too low on the scale will distort the reality of the image and seriously misrepresent the colors in the strobe-lit foregrounds.

When capturing RAW images in a digital camera, the white balance can be properly assigned at the time of capture or, if done incorrectly, reassigned using software in “post.” While considerable control is still possible when shooting JPGs for digital capture, RAW is far more forgiving for correcting deviations in color balance.

With film, there are essentially two choices: Use a special film for each light condition, or use a filter to block a given color cast.

Sometimes cold water is very clear; more often it is not. The wild card is organisms and detritus held in suspension in the water, as it can affect both color and visibility. I typically assume visibility will be marginal and use lighting and composition techniques accordingly to minimize backscatter.

Tip #3

Adjust for ambient light.

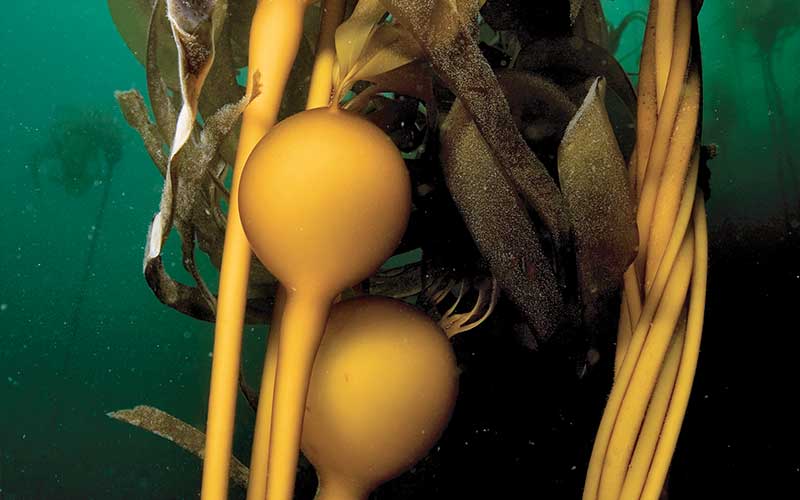

Low levels of ambient light tend to be a major issue in cold waters, whether it is because of ice pack, kelp fronds, suspended particles absorbing light or simply the angle at which the sun strikes the surface of the water. With the camera ISO set to 200, I’ve noticed that light meter readings at 30 ft (9 m) are usually around f/8 in the tropics, whereas in cold water f/2.8 is more the norm. The angle of light is important to consider as well.

Vertical light. This is the light that penetrates from the surface and is modified by cloud condition, time of day, surface conditions, water clarity and depth. Obviously, sunny days transmit more light than cloudy days, noon more than dusk, slick water more than waves, clear more than turbid and shallow more than deep. The best solution to dealing with low levels of vertical light is to slow down the shutter speeds to allow more ambient light in the background. This is especially important in wide-angle shots.

For wide-angle shots of sedentary subjects, I recommend shutter speeds of 1/30th of a second and slower. This does not affect the strobe light striking the primary subject in the foreground but can change a background from black to light green. The other way to get more ambient light in the background without overexposing strobe-lit foregrounds is to combine wider apertures with a lower strobe power setting. If greater depth-of-field is still required, going to a higher ISO will work wonders.

Horizontal light. Even at strobe-to-subject distances of 3 ft (1 m) or less, the power settings and apertures that work in tropical waters will need refinement. Not only does the water column absorb more light, many of the creatures, as a function of their protective coloration, reflect less light than their Caribbean counterparts. As an example, look at the difference in color between a Caribbean octopus and a giant octopus from British Columbia. Clearly, a subject whose environment includes a white sand bottom will need different stealth strategies than one who lives among dark rock and kelp. Thankfully, the digital review will give instant feedback on exposures, but assume more light will be necessary for both vertical and horizontal considerations.

Tip #4

Sharpen your focus.

Low light levels at depth and lack of contrast between subject and background make it difficult to depend on auto-focus in cold water. Sometimes the sheer density of life cloaking the rocks in places like Alaska or the Poor Knights in New Zealand is so extreme the camera can have a hard time discerning precise focus. This is where a good modeling light can be a huge asset. It can be the light built into the strobe, like the LED beam on an Ikelite DS160, or it can be an external auto-focus assist light from lighting specialists such as Light and Motion or the popular new FIX LED Focus lights from Fisheye. Ultralight Control Systems also makes a variety of adapters that thread into an accessory mount on a housing to mount flashlights from a variety of manufacturers. It isn’t rocket science to fix the auto-focus deficiencies that happen in dark water, but unless you come prepared, the dives will be frustrating and the “keeper-rate” will go low.

There may be circumstances where auto-focus simply won’t work, so serious cold-water shooters must learn to embrace manual focusing. The best housings offer the creative control to access either manual or auto-focus, but the lenses typically have to be equipped with focus gears.

Tip #5

Get close.

With so many small, colorful creatures in cold-water environments, a macro-telephoto lens is very useful. While many of the sessile creatures will tolerate the closer proximity required to fill the frame with a 60mm macro lens (speaking in full-frame equivalency), compositions from a greater distance allow greater flexibility in strobe positioning. The more skittish creatures are best approached at a slightly greater distance anyway.

The size of the subject and the proximity it allows will pretty well determine the optimal optic. If that happens to be a large marine mammal, like Nicklen’s classic leopard seal, a wide-angle lens is crucial. Medium-sized fish like Pacific octopus, sculpin or wolf eels are perfect for zoom lenses like the Canon 17-40mm that focus close but have the versatility to cover both wide scenics and marine life portraits. Your macro lenses will get a good workout in cold water, as they allow magnification of 1:1 and closer (for those incredibly colorful and intricate invertebrates), and they typically lock focus very efficiently in low light.

The point is not so much about exactly which lens to use but to recognize that the best photos will occur at very near distances. Getting close to your subject also enhances strobe penetration, minimizes backscatter from suspended particles and ensures the best possible image resolution.

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2009