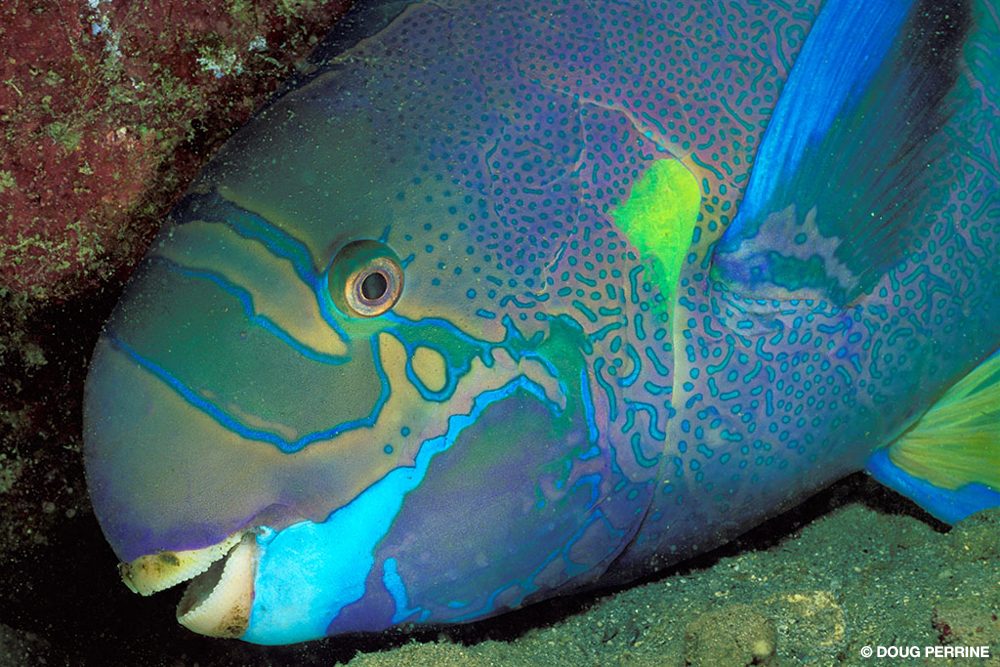

CHARLES DARWIN’S FIVE WEEKS IN THE GALÁPAGOS Islands were crucial to the development of his theory of evolution, likely due to the Galápagos having the world’s second-highest proportion of endemic (unique to one location) species. What if Darwin had instead visited the islands with the world’s highest rate of endemism? If Darwin had the chance to examine some of Hawai‘i’s unique and beautiful fishes, today we might be talking about Darwin’s fishes instead of Darwin’s finches.

Most of the Galápagos Islands and surrounding waters are now protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, biosphere reserve, national park, and marine reserve, attracting ecotourists by the hundreds of thousands. In contrast, Hawai‘i’s main inhabited islands host relatively few fully protected natural areas, and few visitors to Hawai‘i focus on the islands’ unique plant and animal life. Few laws protect endemic marine species, and there is less enforcement. Hawai‘i is more widely associated with leis and luaus than rare and unique wildlife.

While recreational diving and snorkeling contribute to the economy, endemic fish tours are pretty much nonexistent, in part because many endemic fish are not easily observed, because collecting and spearfishing have reduced their numbers and because these activities train them to hide from humans. More people have probably appreciated Hawaiian fish in aquariums elsewhere than on reefs in Hawai‘i. Escalating prices for rare Hawaiian species led collectors to go deeper and deeper to find prized fish, leaving a paucity of specimens within recreational diving depths.

A study in the mid-1990s showed that seven out of 10 aquarium species studied suffered significant population reductions as a result of collecting. In 1998, Act 306 established the West Hawai‘i Regional Fisheries Management Area on the Big Island and a management council with a mandate to create no-collecting areas. Subsequent studies showed that the two most-collected species, yellow and kole tangs, experienced such impressive recoveries within the closed areas that their populations spilled over into adjacent areas of the open collecting zones. Drastic declines within the open areas were avoided despite increased collecting pressure, eventually leading to increases in the open areas as well.

In 2013 Hawai‘i created a white list of 40 species that aquarium collectors could legally take in West Hawai‘i, including several endemic and rarely seen species. A lack of inspections and enforcement led to widespread suspicion that protected species were being poached and that high-value fish were not safe even in the closed areas. Divers complained that they hadn’t seen once-reliable species for years. When word spread that divers had found a certain fish at a particular site, the fish would often disappear within days.

Collectors argued that some of these “scarce” fish are common in deeper water. With reserve populations on deep reefs and around the remote uninhabited islands, they contended, it would be impossible to wipe out the species. This argument carries weight biologically but offers scant solace to fish watchers.

In addition to disgruntled divers and tour operators, animal rights groups got involved in what became an annual tussle at the Hawai‘i legislature. They cited studies showing that many reef fish live decades in their natural habitat but have short lives in captivity. Some do not even survive capture and transport.

Coral-bleaching events in 2015 and 2019 gave the anti-collection lobby more ammunition. The tangs that comprise the bulk of fish collected in Hawai‘i are herbivores that help control algal growth, which is essential for reef recovery after devastating marine heat waves fueled by climate change. State biologists, however, joined collectors in testifying that the fishery was well managed. Former collector Bob Hajek insists that most collectors were good stewards of the reef. “Why would we overharvest and put ourselves out of business?” he asked. Bills to ban collection failed every year.

Activists eventually had better luck in the courts. In 2017 the Hawai‘i Supreme Court ruled that the state had violated Hawai‘i’s laws by not requiring an environmental impact statement (EIS). Collectors submitted an EIS, but it was challenged and ruled inadequate by the courts. Aquarium collecting was legally closed in West Hawai‘i in 2018 and statewide in 2021. The West Hawai‘i injunction, however, was reversed in January 2023, but that decision has been appealed. In the meantime, the state has the authority, but not the obligation, to issue new collecting permits.

Some divers claim a dramatic improvement in fish sightings since the closure of collecting. “Over the past four years, since the aquarium trade stopped, I’ve noticed some of the rarer species, especially Tinker’s butterflyfish, at a lot more sites,” said avid diver Pam Madden. “I used to see them rarely, and they would be very skittish. Not only am I now seeing them at more sites, but they also are not as shy. Without that collecting pressure, they are more interactive and play with your bubbles. It’s such a joy to watch them!”

Madden and others report having much more success recently finding the spectacular Hawaiian flame wrasse and other endemics. Data from the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) supports these claims. For 28 species of Hawaiian endemic fish plus the near-endemic Tinker’s, I calculated the averages for 2015-2017 and 2020-2022 (during and after collecting) in West Hawai‘i, and compared the changes. Trends varied among different species, but overall there was a 33 percent increase in sighting frequency and a 6 percent increase in density. For some species, the difference was dramatic. Tinker’s butterflyfish showed a 300 percent increase in sighting frequency and a 75 percent increase in density. A smaller dataset from the the Hawai‘i Department of Aquatic Resources showed an average density increase of 64 percent across 22 species.

Several organizations are working to refine techniques for the captive culture of some Hawaiian fishes. Some are in the early stages of commercializing that process. Tank-grown yellow tangs and a couple of endemics may become readily available as early as this year. The long-term success of these ventures may ultimately depend upon how much competition they face from collectors who are not saddled with the costs of maintaining a research laboratory and expensive captive breeding and grow-out facilities.

Whether aquarium collecting will resume in Hawai‘i remains unknown, along with how climate change will affect Hawai‘i’s unique reef life. We do know that now is the best time in years to appreciate the exotic and beautiful native fish that Darwin unfortunately missed on his transformative voyage. AD

Explore More

© Alert Diver — Q2 2023