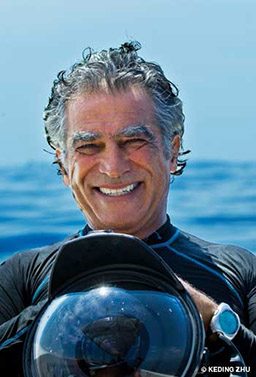

It is appropriate that an article on the photography of Amos Nachoum should appear in the same issue of Alert Diver as a feature on the Red Sea, for the genesis of Nachoum’s career is inextricably linked with diving there.

Nachoum and I first intersected in 1982. By that time I had begun to build a decent portfolio of underwater images from my home waters of the Florida Keys and the Caribbean, but I had yet to shoot a clownfish or a lionfish or even a bit of soft coral. I knew from the published work of Rick Frehsee and others that the clear waters and spectacular coral reefs of the Red Sea offered the best potential for what was to be my first exotic photo tour.

This was long before there was such a thing as Internet research on dive destinations, and message boards were a remote and nascent concept. To learn about where to go for diving, we read magazines (usually Skin Diver in those days) and talked to those who had personal experience in the region.

For the Red Sea the go-to guy with local knowledge was Nachoum. He is Israeli, and at that time the Red Sea was under Israel’s control, at least in practice. As a result of the 1978 Camp David Accords, the Sinai Peninsula and much of the Red Sea was ceded to Egypt, but the transfer of governance lagged a few years behind. Nachoum had founded a dive travel company, La Mer, especially to facilitate recreational diving in the Red Sea, and it was with La Mer that I chartered my first liveaboard dive boat and led my first exotic photo tour. I recently caught up with Nachoum to fill in the blanks about what preceded that era and discuss where his career has taken him since.

STEPHEN FRINK// So I know you originally from the days when you lived in New York and ran La Mer Diving Seafaris, which you promoted with bold, full-page ads in Skin Diver. How did you morph from a kid in Israel to a dive entrepreneur in New York City?

AMOS NACHOUM// It was a big step for me, but as a child growing up in Israel I always wanted to be a photographer. The travel hook came much later, but photography was my first passion. My father was a soldier during World War II and during the creation of the state of Israel, and we had around the house complicated cameras with bellows, brass and chrome. He also had photos from his time fighting the Nazis. Not that he wanted me to be a photographer, however. In fact, the demands of youth were different in Israel, and I was expected to be an electrical engineer. Yet, I was intrigued by the images he took, the stories behind them, and the complexity of the camera. Still, it was a path I had to walk alone.

As with many others, my time in the Israeli army forged a new direction. Military service in Israel is compulsory, for both boys and girls, and my service was with the Special Forces. Aside from the specific tasks I was assigned, I did war photography for fun, if you can call it that. I took photos and shared them with friends. I started doing it when I was 18, and I stayed with it until I was 25.

SF// War photography is very different than what you do today. Was there a watershed moment that shifted your perspectives?

AN// After I got out of the service (the first time) I apprenticed as a fashion photographer for a year. That was a very interesting time for me, and I learned the relevant fundamental skills such as black-and-white darkroom work, working with strobes and directing models. Maybe not all of that is relevant to me today, especially since my models are large marine animals, and they are very poor at taking direction. But it was good training, even if I did decide to go back into the military for another three years.

Then it was all about journalism. I was embedded on the front lines and had opportunities to document battles for the Associated Press in Israel — stories that got worldwide circulation. I shot black-and-white and color negatives as well as medium-format color slides. But it got to the point where blood, smoke and fire wore me out. It was exciting, challenging and emotionally disturbing, but I’d had enough of that life and moved on. The next chapter of my life was entirely different. Three friends and I went into the yacht-delivery business, and I got to see a lot of the world pass beneath our bows.

As for New York, I was still bumming around but had a dream to learn television and film. With nothing in particular to lose, I moved there, going to school at New York University at night and supporting myself driving taxis. I could barely speak English then, so I fit right into the local cabbie scene. I wanted to improve my language skills, so I found a job with Atlantis II dive shop in Manhattan, working with dive icon Butch Hendricks. That forced me to speak English and learn the vocabulary.

SF// What happened to your dream of being a filmmaker?

AN// I was in a wonderful program at New York University. The year was 1980, and my dream class had three teachers: Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen and Francis Coppola. There were 400 applicants for this class, and we all had to show our work and then be interviewed to be accepted. Incredibly to me at the time, I was one of only 35 invited to move on to advanced studies. But I couldn’t afford the tuition. That was essentially the end of that dream.

Yet my days of wandering the globe on other people’s yachts suggested I was good at travel — organizing logistics and executing complicated tour itineraries. A friend of mine from the service joined me, and we decided to promote the dive attractions of our home waters in the Red Sea.

SF// I remember my first trip to the Red Sea in the early 1980s. In Sharm el Sheikh there was only one resort, and it was divided between rooms in the hotel and tents on the beach. Hurghada was even more primitive — nothing at all like the tens of thousands of posh hotel rooms found there today and a dive fleet with hundreds of liveaboards. What was it like selling dive travel to the Red Sea in those days?

AN// Our first seafaris were aboard camels and Jeeps. I soon realized this was too crude for the American market and decided a liveaboard was the way to go. I found a suitable tourist boat in Eilat and led the conversion of the boat for diving. That became the Sunboat you chartered, with private cabins and compressors onboard. We even had E-6 film processing on board with a small Jobo system and a primitive darkroom.

Seeing that the end was near for an Israeli operating in the Red Sea, we expanded to other destinations and by 1987 represented 15 liveaboards in places like Papua New Guinea, Little Cayman, the Solomon Islands, Australia and the Maldives.

SF// Today La Mer is no more. What happened?

AN// Basically, I got burned out. I still wanted to be a photographer, but I had become a businessman. We sold the company, and I set out to find what I could do in underwater photography. I was actually a bit disillusioned with what I was seeing in the dive media of the day. Ninety percent of everything published seemed to be about macro or divers.

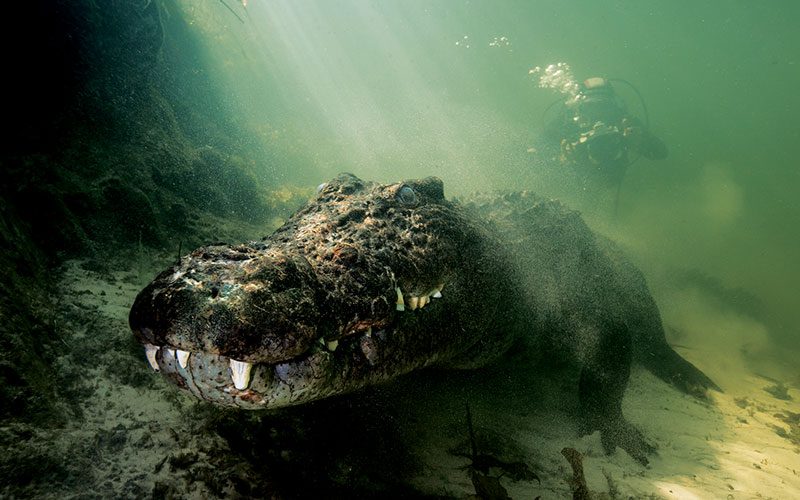

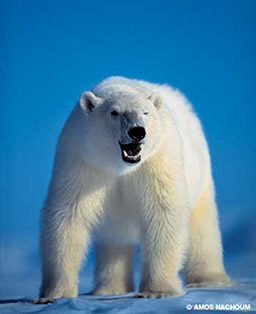

Nobody was covering the ocean giants I so revered, and even if there was an article about megafauna, it seemed to emphasize the danger instead of the glory of such an encounter. I’d seen orcas, great whites and whales by then, and they were what motivated me.

That’s what the travel company I now run, Big Animals Expeditions, is all about. I figured I could find a few souls with a sense of adventure like mine, and we could share something special in the sea. I had some experience leading small groups of filmmakers during charters that the BBC and National Geographic booked with La Mer, and that was my concept. I would specialize in small groups and target just a single species at a time, to be there at the prime season for optimal behavioral activities, whether it was breeding or predation or migration.

SF// Do you even shoot macro or reef scenics on these trips?

AN// Not really. I travel with a Canon 1Ds Mark III and a 1D Mark IV in Seacam housings for my underwater work and bring only wide-angle lenses such as the 8-15mm, 14mm II, 15mm, 16-35mm II, 24mm f/1.4 and the 50mm f/1.2. I’ll bring a Canon 1D X body and a 600mm telephoto plus tripod if I’m going to Antarctica, Africa or India for the snow leopard. But I’m not the guy who prowls the reef with my 100mm macro searching for nudibranchs. For me it is all about big marine life.

SF// I’ve noticed your coverage of many destinations tends to be among the first. Take sailfish off Isla Mujares, for example. I’ve seen a lot of shooters visit there in the past few years, yet your images of the billfish there are the first I saw. That had to be a bit of a risk to try for the first time — not knowing whether you’d spend considerable time and money and get skunked.

AN// Well, first of all, I don’t go into these things blind. Every two years there is a big marine-mammal conference, and I attend to sit among highly educated people and listen to what they are doing and where. I make connections with the researchers, and of course I try to connect with sport fishermen. That first trip for sailfish was done with one of the most well-known of all billfishermen, Guy Harvey. Another big breakthrough, photographically, for me was my early work with orcas in Norway. In 1992 a guy came to DEMA from Norway promoting the chance to swim with orcas. The next year I was there when no one else wanted to go. It was a risk, but a calculated one based on diligent and detailed research and a willingness to gamble.

I figure if I want to do one of these adventures, there must be others like me. If you look at some theories of psychology, particularly neurolinguistic programming, they posit that there are only six or seven distinct types of personalities. With 7 billion people on the planet, there must be a billion who think like I do. Of those, I need 50 or 60 a year who are divers and photographers and who have the means and desire to go on a grand adventure.

SF// Many of these trips are to very remote locales. Have you or your guests ever been hurt?

AN// Thankfully, I have a perfect record with my guests. No one has ever been hurt on one of my expeditions. I can’t say the same for myself though. In 2002 on my way to Antarctica I was walking down some steps on a ship. The seas can be massive on that crossing, but we were actually in calm waters. The railings were iced over, and I just took a bad step. I had a 35-pound Pelican case with camera gear in my hand, and I started rolling down the steps … hard. My head hit the rail, and I ended up on the deck unconscious.

They called the ship’s doctor, and I got stitches, but I was still in a bad way with a concussion. I needed to be evacuated, but that couldn’t happen until we got to King George Island air base. It consists of a gravel runway, and the only way out is on a Twin Otter aircraft. They dispatch them from Chile but evaluate the weather when they are halfway there. If it is good in Antarctica, they will continue; if it’s bad, they’ll turn back. Most of the time they turn back.

We called DAN on the satellite phone, and everything was arranged when we arrived at King George Island. I can’t credit DAN with arranging the good weather that allowed the evacuation, but they arranged and paid for everything else. I saw the bill, and the evacuation alone cost more than $30,000. DAN paid for the evacuation, the hospital in Chile and even first-class airfare back home. We require DAN insurance for all guests on our expeditions. We hope we never have to use it again, but we are thrilled to know it works.

SF// How do you keep your images in circulation? Are you active in the stock-photography business?

AN// I recognize going into trips like these that my yield may be very small. When it is good, it is outstanding, but it is not like you photographing queen angels in the Florida Keys. There are no guarantees for me; I accept that.

That also minimizes my interest in stock photography or other commercial outlets for my images. I have no patience for applying the metadata and captions and then organizing images and submitting them for the relatively low rate of return on stock photos these days. I keep a small selection of my very best in circulation and concentrate on syndicating some stories after I do the trips. Europe and Asia are particularly good markets for me at the moment — even more so than the United States, in terms of photojournalism.

SF// I see from your website that you have a very active travel schedule in 2013.

AN// Yes, I’m going on location for humpback whales, blue whales, anacondas, crocodiles, sperm whales, sailfish and marlin. You’ll notice when I talk about travel I talk mostly about what the animal is rather than where it is. I will have researched the location, time of year and infrastructure necessary to get the job done, but in the end it is all about the specific animal and how we can put the odds in our favor to get the encounter and capture the image.

Explore More

Watch Amos Nachoum’s TED Talk.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2013