Most people who were scuba divers in 1977 will remember a movie called The Deep, if only for the underwater scenes with Jacqueline Bissett. More than any film, before or since, The Deep was a hybrid of mainstream Hollywood talents and dive industry luminaries.

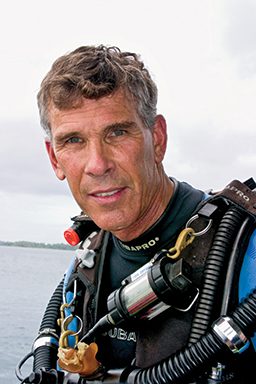

Peter Benchley wrote the novel and screen adaptation. Al Giddings, Stan Waterman and Chuck Nicklin handled the underwater cinematography. David Doubilet was hired to shoot the underwater stills, and Geri Murphy provided underwater continuity. Jack McKenney was on the shoot, too, as a stunt double for Nick Nolte.

Yet there was another guy you’ll never see mentioned in the filmography, the guy they hired for $100 a day to spear the fish used to attract sharks: Howard Hall. The significance of that fact is that they gave him 25 days of work, and $2,500 was huge money for a kid working in a dive shop at the time. All that money and a year of Hall’s life went into building his first underwater movie camera.

While that would seem to be the pivotal event in the life of a filmmaker now famous for his spectacular underwater IMAX movies, the journey actually began much earlier — in 1966 to be exact — when a 16-year-old Hall earned his L.A. County scuba diver certification. That led to part-time jobs at several Southern California dive shops, but the planets really started to align for Hall in 1972 when he was hired at the Diving Locker, San Diego’s legendary dive shop. There he got to know underwater photographer/filmmaker/dive shop owner Chuck Nicklin and Nicklin’s sons, Terry and Flip. Aficionados of pelagic wildlife photography will immediately recognize the name Flip Nicklin for his work with whales and dolphins for National Geographic. Another kid working at the shop about the same time was Marty Snyderman, now an internationally recognized photographer.

There must have been some infectious “photo pheromones” at work at the Diving Locker in those days, but to shine in that firmament required Hall to go out and buy a Nikonos camera and a set of extension tubes to teach himself underwater photography. He was a quick study, and before long Hall found himself doing less and less scuba instruction and more and more photojournalism.

SF: Howard, what did it mean to be an underwater “photojournalist” back in the early 1970s?

HH: Well, mostly it meant that I’d figured out that I could better market the photographs I was taking if I wrote the words, too. Back in those days I was writing articles about marine life behavior, illustrated with my still photographs, and selling them to Skin Diver.

But I wasn’t stupid. I looked at the page rates they paid in a dive magazine as compared to other places I had a chance to get published, magazines like National Wildlife, Natural History, National Geographic and Geo. Clearly, general interest magazines paid better, and that’s where I put more of my efforts. I got pretty well known for marine life photography back in those days.

SF: I was in the Florida Keys, and you were in San Diego, but we were both just starting out in the business of underwater still photography about the same time, back in the late 1970s. I remember reading your 1982 book, Howard Hall’s Guide to Successful Underwater Photography — which was very inspirational, by the way — and hearing for the first time a name applied to a technique called “close-focus wide angle.” I think that particular book had greater resonance for more aspiring underwater shooters than any other instructional text. In fact, I still see it quoted with reverence in online chats. How did that come about?

HH: The book was a product of frustration. While I was learning to take photographs underwater, I constantly searched for books that explained how specific images were made. I could find everything I wanted to know about what an f-stop is, shutter design, film emulsions, but nothing on how you operate a camera underwater to produce a specific effect. What I really wanted was a book filled with good underwater images and captions that revealed what gear and technique was used.

Eventually I figured out how most of the images I saw published were made. I decided that there were probably other beginners out there who were just as frustrated as I had been when I was learning. So I wrote the book. In it, I categorized underwater images as either silhouettes, macro, negative space, available light, people photography and, yes, close-focus wide angle. Then I explained in detail the gear and technique used to make them.

By the way, I dreamed up the term “close-focus wide angle” to describe a technique that Marty Snyderman and my other buddies at the Diving Locker called a “Jerry Greenberg” photo. It may seem absurd now, but I can remember looking at images like his famous porkfish school featured in your last Alert Diver issue and being totally baffled. How did he keep both the foreground and background in focus? We actually thought he might be sandwiching two images together. Literally years went by before Marty and I figured it out. When I wrote the book, I considered sticking with our original name for this technique, the “Jerry Greenberg.” But I worried about how he might react. So I dreamed up “close-focus wide angle.”

SF: I’ve always felt you were one of the great talents in underwater still imaging. What motivated the migration to film?

HH: The reality is that at the time, and probably still today, there was a survival instinct at work. It was very difficult to make a living as an underwater still photographer. It’s not like I made the conscious effort that if I wanted to get rich, I should start shooting films. But once I started shooting movies I noticed three things: Films paid better, the assignments were longer, and there was less competition for the assignments.

SF Which brings us back to that $2,500 you made on the set of The Deep. What camera and housing did you buy?

HH: None. I made one myself! I took a used Bell and Howell “wind-up” movie camera and removed only the gate to use in my new camera. We purchased a 12-volt electric motor, and my machinist built everything else. The mechanism was installed into a cylindrical housing that could take any “C” mount lens, my favorite being a 10mm Switar. At the time, the commercially popular 16mm movie camera and housing combination came from Bolex and had a wind-up spring that ran for 15 seconds. My housing had a motor that could run for 10 minutes! That was a huge differentiator. I used this camera on many early episodes of American Sportsman and Wild Kingdom.

SF: I read a lovely article about your wife, Michele, in a copy of Diving Adventure. She talks about your early years shooting movies as an itinerant cameraman: “Have Camera Will Travel,” she called it. What was that like?

HH: For a decade (1978-1988), I shot a lot for diving adventure shows, including 16 episodes of Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom. Like most cameramen I didn’t own any of the footage. I got to shoot stills while we were on location, and I could sell that as stock, but the 16mm film went to the production company. Gratefully, people came to know my work and trusted my skills, so when I pitched PBS Nature an idea I had to produce my own film on the kelp forest, they were willing to take a chance. The year was 1988, and the film was Seasons in the Sea. It went on to be spectacularly successful, winning Best of Show at the Wild Screen Festival and the Festival Choice at Jackson Hole.

At a time when wildlife filming was really at its peak, having those awards pretty much meant I could broker my own deals. I got to own all the footage that I shot on Seasons in the Sea, and that was my new model. When I was in pitch meetings with people like National Geographic and they explained their terms, which involved the industry standard of them owning the footage, I was prepared to walk away. If I did the work, I owned the film. Shadows in a Desert Sea on the Sea of Cortez came next and then Jewels of the Caribbean Sea.

Eventually Michele and I made our own series, Secrets of the Ocean Realm. But in the end, I felt my entire career was founded on the success of Seasons in the Sea. It allowed three things that ended up being huge to me: I could make my own deals, I could own my own library, and I had big enough budgets to do better productions than others might.

SF: With that many films in 16mm, you must have a massive library of archival footage.

HH: Not really, at least not in 16mm, anyway. A famous cinematographer and friend of mine, Wolfgang Bayer, sold his archive in the early 1990s, and it sounded like a good move to me too. I knew high-definition television was coming, and the aspect ratio was different than 16mm. I felt high-def was the format of the future, so I hired an agent to sell my library.

SF: How did the IMAX connection happen?

HH: The year was 1992, and I actually got a phone call from Graeme Ferguson, which at first I thought was a prank, because you couldn’t be in the film business and not know of Graeme Ferguson. He’d founded the IMAX format and established the theaters, and now he was working on a concept for IMAX to be in 3-D. He’d seen Seasons in the Sea and thought an underwater film would be the right way to do the first of his 3-D projects. Of course, they hadn’t actually finished building their $2.5 million 3-D camera yet.

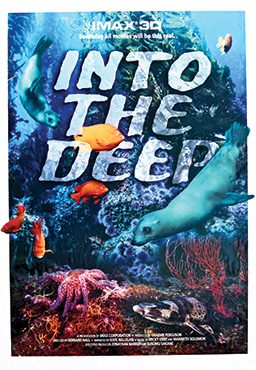

When they did finish it, Bob Cranston and I worked with them on the development of the housing. Actually, a couple of years went by between that phone call and the production of Into the Deep 3-D, but meanwhile I was busy with our National Geographic special Jewels of the Caribbean Sea and MacGillivray Freeman’s IMAX film The Living Sea. Greg MacGillivray was nominated for an Academy Award as producer on that one, and I was the director of photography.

SF: Once you kicked into high gear with that first IMAX film, it seems you never looked back. What were some of your other IMAX projects?

HH: OK, let me think about the films:

- The Living Sea – director of underwater photography

- Into the Deep 3-D – director

- Island of the Sharks – director; Michele Hall was producer

- Coral Reef Adventure – director of photography and talent; Michele and I starred in that one

- Journey into Amazing Caves – underwater cinematographer

- Lost Worlds: Life in the Balance – director of underwater photography

- Deep Sea 3-D – director; Michele co-produced

- Under the Sea 3-D – director; Michele co-produced.

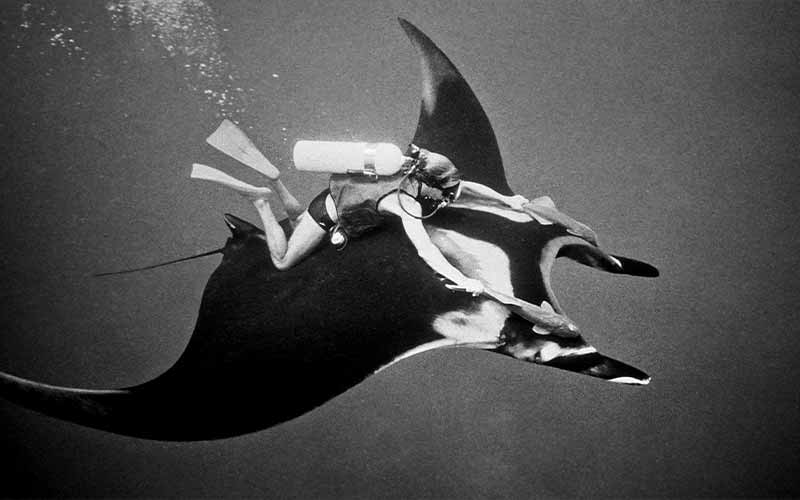

SF: You are synonymous with rebreather technology in filmmaking. Is it all about getting close to the marine life?

HH: People always assume that silence is our motivation for using our rebreathers — highly modified Biomarine 15.5 systems — on our film productions, and no doubt it would help more except for the thunderous noises an IMAX camera makes when running film. It would be an exceedingly stupid fish not to notice that.

For me, it is far more about time. So long as we are willing to invest time in the decompression, our rebreathers allow massive bottom time. With my system, I can stay down for 12 hours, not that I ever actually stay that long. But on my last film, I wanted a shot of a stonefish feeding, and I spent 6 hours waiting for the behavior to happen. I stay until the job is done and then do as much decompression as necessary.

SF: As this is a Divers Alert Network® publication, I’m wondering how DAN® might fit into your production’s “workflow?”

HH: First, we require DAN insurance of all crew on every production. No one — divers and nondivers alike — goes out on our charters without proof of DAN dive accident insurance. And then, of course, I’ve had need of DAN’s insurance on my own medical situations.

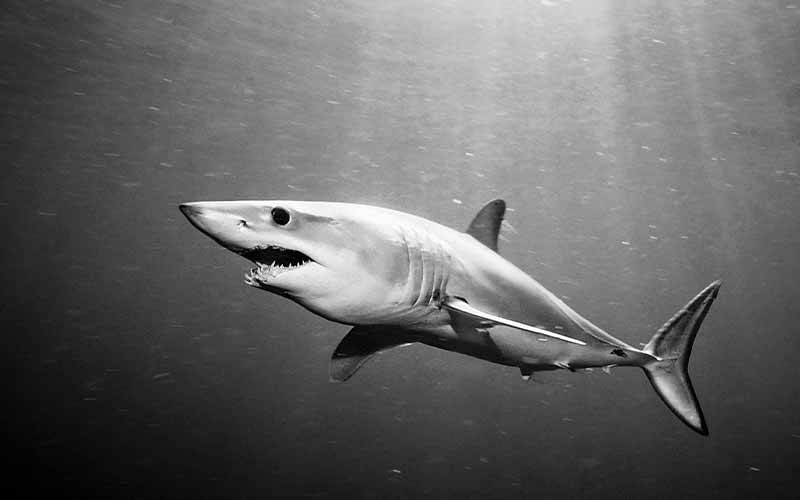

I really appreciated DAN during the production of Coral Reef Adventure in Fiji. We were diving deep, 350 feet or so, and on my 50-foot deco stop I got bent. I know you’ve been bent, but I would guess it happened on the surface. I was at 50 feet with sudden and severe abdominal and back pains, classic symptoms of a spinal cord hit. Since I was on a rebreather and had plenty of gas, I dropped down to 70 feet and immediately felt better, and by the time I got to 100 feet I felt fine. We all carry in-water recompression tables in our BCD pockets, so I started to do what I had to do to get back to the surface.

SF: How did it turn out?

HH: Actually, I felt fine when I got back on the boat and assumed I’d dodged a bullet. But later that night I had more symptoms, so I got back in the water for more in-water recompression. I’m not recommending people do this, and I’m sure DAN has advice on whether to do in-water recompression or not, but we were a long way from the chamber in Fiji, on a liveaboard boat, and I had to do what I could for myself at the time.

[Editor’s note: In-water recompression has its own dangers and should not be attempted without the necessary training and equipment. As a rule, DAN does not recommend the practice.]

When we finally got back to port, I went to the chamber and did multiple recompression rides there. Of course, DAN took care of the bills for my chamber treatments. Seriously, we would never go on a project without the protection of DAN insurance.

Speaking of dive-related injuries, I had the first case of hyperoxia-induced myopia that DAN had ever heard of! We had just wrapped filming Island of the Sharks, and I was in the Dallas airport and realized I couldn’t read any signs. My vision was so bad that Michele had to lead me to the gate. As it turns out, diving five hours a day for 27 days straight at Cocos Island, breathing an oxygen partial pressure of 1.3 ATA had consequences no one knew about at the time.

When Michele contacted DAN about my condition, medical personnel didn’t have the answer themselves, but they did provide an excellent referral. They told Michele about a U.S. Navy ophthalmologist, Capt. Frank Butler, doing work with SEAL teams. She called him and left a message with one of his ensigns. Despite being on vacation, he called back the very next day and said, “I know what you have!”

Hyperoxia-induced myopia happens because oxygen toxicity damages the lens in the eye so it is less flexible and can’t focus. Dr. Butler said my vision would return to normal in about four weeks and to buy some glasses in the meantime.

He was right, it did get better — the first time. But on subsequent rebreather dives I found my vision got poor more quickly and took longer to get back to normal. Now I, and the other members of my team, avoid breathing high partial pressures of oxygen as much as possible. In fact, Dr. Butler has done research on the vision of our whole team while on location, and he found there was temporary deterioration in our vision after each day of diving; the older we were, the more it shifted. I didn’t have it in mind to be a case study, but there’s not a great body of knowledge to support the kind of diving we do on our film projects. Sometimes we learn as we go.

SF: So after all these years and all your success in filmmaking, can you stay passionate about the underwater world?

HH: Absolutely! What I like to do, what I like to see, is animal behavior. I don’t really care if it is big or little, but I’m an underwater voyeur blessed with a long attention span. I’ve been very lucky to be at the right place at the right time many times throughout my career, and I’m very lucky to have a wife who shares my passion for diving and the business of our film productions. But none of this ever started because I thought it might be commercially viable. It was just what I wanted to do. Fortunately for me, the things I got to see underwater and bring to televisions and IMAX screens were the things that people wanted to see.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2010