Few people will know a person better than his longtime dive buddy, so for an introduction to Roger Steene we turned to Walter Starck, Ph.D., an accomplished marine scientist and underwater photographer — and longtime friend of Steene’s:

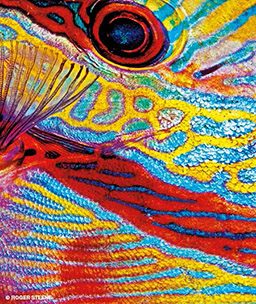

The photographs in this article are the result of one person’s love affair with coral reefs. For more than 40 years Roger Steene has spent several months of every year diving and photographing on reefs around the world. His motivation has been neither that of an academic following a career nor that of a photographer pursuing a livelihood. To capture first on film, and now on digital media, the wonder and beauty he finds on the reefs has been his abiding desire. In so doing he has amassed an extraordinary collection of images and has published 13 books. Roger operates by his own standards alone. The images he rejects are often excellent photos by any standards. Invariably when he returns from a diving expedition and examines his photos he is mildly disappointed that somehow his results, no matter how good, do not fully convey the ultimate beauty of the subject. This dissatisfaction becomes determination to go back and do the whole thing over again to capture the ultimate elusive nuance.

Roger Steene is, like the reefs he loves, a remarkable phenomenon. For 10 years I had the pleasure of his company aboard my research vessel El Torito for a couple of months each year on the Great Barrier Reef and the Coral Sea. His enthusiasm is infectious, and at times, such as at a new diving location on a perfect day, it becomes almost uncontrollable. This enthusiasm is not limited to reefs. He loves good food, good friends, good times and life itself. When Roger was aboard, everyone seemed to catch his enthusiasm and enjoy themselves even more than usual. In many respects he is the quintessential Australian: a larrikin — irreverent, fun loving and scornful of all pretension.

We celebrate herein not only the career of marine naturalist and underwater photographer Roger Steene but also the publication of his grand masterpiece, Colours of the Reef. Weighing 30 pounds with nearly 7,000 photos and 1,400 pages, this three-volume set is a limited edition of just 900 copies priced at $320 per set (see fishid.com/colours.html).

Few who survive a serious motorcycle accident emerge without significant trauma or a new outlook on life. This was certainly true for 17-year-old Roger Steene, whose accident in 1959 indirectly set him upon a new and enduring path in life. He came out better than the others involved (two died in the crash), but his right knee was effectively destroyed. While all the young Australian’s friends were active in team sports, the only place he could achieve total mobility was underwater. Living in Cairns, the gateway to the Great Barrier Reef, was a blessing in that regard, and Steene took full advantage.

Around that time he was playing drums in a band with an ongoing gig on Green Island, a tourist destination far enough offshore to be blessed by clear waters and a developed coral reef but near enough to accommodate short holidays from mainland Queensland. The Nikonos 1 camera had just been released, and Steene took his very first underwater shots with this rudimentary equipment. It wasn’t long before he learned that to achieve color he needed artificial light, but in those days that meant carrying 36 flashbulbs underwater to shoot a roll of film. Primitive though his system might have been, there were few others shooting underwater at the time, and the novelty of his photos provided entrée into the photojournalism market. In the early 1960s he was supplying black-and-white pictures to the region’s nascent holiday tourism industry.

The big turning point in Steene’s career happened in the early 1970s with a chance meeting with Gerry Allen, Ph.D., an American ichthyologist who had just moved to Australia. (See alertdiver.com/Gerry_Allen to understand the significant impact Allen has had on the science of fish identification.) Steene was a young man driving to and from his boat in a dinghy in the same marina where Allen was living on Walt Starck’s research vessel. Whatever random karmic synchronicity brought these two together proved a boon to the art and science of fish identification and led to a friendship and a collaboration that have endured for more than 40 years.

Starck reminisces about those days:

In 1972 I arrived in Cairns, Australia, aboard El Torito from the U.S. via Micronesia and New Guinea. With me was Gerry Allen, his wife, Connie, and their son, Tony. When I flew out to Sydney to edit and sell a documentary film I had shot in New Guinea, Gerry and his family remained with the boat. My stay in Sydney stretched to five months. During that time Gerry met Roger Steene and began a close friendship that has endured.

This was Roger’s real introduction to the scientific study of reefs. At that time he had his own boat and was already an avid underwater photographer with years of experience. His meeting with Gerry was a turning point. You photograph what you see, and what you see depends greatly on what you understand. The profusion of life on reefs is confusing, and knowledge of its biology at the time was limited and not readily accessible. Only recently have guidebooks and reference texts become available. Scientific knowledge was largely couched in arcane jargon and hidden in obscure journals. Much of what was known was then unpublished. Roger’s introduction to the scientific community, via Gerry, afforded him access to this knowledge. Since that time most of Roger’s diving has been done in the company of biologists.

STEPHEN FRINK: I first became aware of the artistry of your underwater photography in your 1998 bookCoral Seas.I was impressed with the sheer volume and diversity of the marine life you’d captured, but I also came away with the sense of a fine aesthetic. It was as if a simple fish portrait was not good enough for you, and you wanted to imbue these creatures with personality. I also came away with a sense of the massive amount of time you must spend underwater to capture a body of work like that we see inColours of the Reef.Describe a typical Steene photography dive.

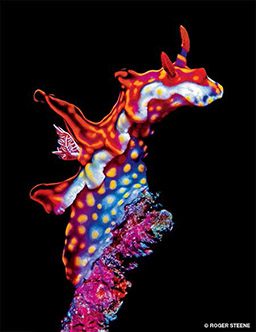

ROGER STEENE: I did a lot of diving on the Great Barrier Reef when I was beginning my career as a fish naturalist and photographer. As time went on I found my favorite places to dive were those with the greatest biodiversity in the Coral Triangle, and I’ve now spent a huge amount of time in Indonesia, the Philippines and Papua New Guinea.

A two-hour dive is pretty typical for me, and I’m often in muck habitats looking for new or different species to photograph (or perhaps those I’ve done before and now hope to do better). I try to isolate myself from divers I don’t already know, and I end up with people interested in the same things I am — people such as Ned DeLoach, Gary Bell, Gerry Allen, Peter Parks and Richard Pyle. I like it in the shallows, where I have almost unlimited time to be with the fish and to capture their behaviors. I’m happy enough to be in 1 or 2 meters of water, and if it’s muck with poor visibility, that’s fine with me. I’ll find the fish, and maybe there will be a new one for me.

When I started out I was collecting specimens and sending them to the Australian Museum in Sydney. They made me a research associate, as did the Western Australian Museum in Perth, and I’m very proud of these accolades. We discovered the science of fish identification could also be advanced with good photographs, and soon Gerry and I were taking pictures of all the different fish we could find. It has only been in the past 20 years or so that I branched off into invertebrates.

SF: As we discovered in our Shooter article on Ned DeLoach, fish ID specialists seem to favor a fairly standardized underwater photo kit that works for them. Do you have a preferred system that you use for your underwater photography?

RS: After I realized the shortcomings of my old Nikonos camera for fish and macro photographs, I migrated pretty directly to a film single-lens reflex (SLR) camera, which in that era was a Nikon F. It had the option to add a large action finder, which made it much easier to do fine focus behind a dive mask, and the 60mm and 105mm Micro-Nikkor lenses were a revolution at the time. I used them with an Ikelite housing and a housed Nikon strobe. I can’t say that particular strobe was the best option compared to modern submersible strobes, but as it got me away from using a flashbulb on every shot it was a massive improvement.

My cameras followed the general evolution of the Nikon SLR from the Nikon F to the F2 and then the F4 before I finally transitioned to digital with a full-frame D700 in a Nexus housing. For a long time I stuck with the 60mm and 105mm macro lenses, but then I discovered the Nikon 70-180mm macro lens, and I now use that almost exclusively. With that lens I can fill the frame with a nudibranch only a quarter-inch tall, or I can back off and fit a 5-foot shark in the frame. And I love my Nexus housing, by the way.

Probably the greatest difference between the way I shoot and the way others might is the lighting I use. Where so many use twin strobes on articulated arms, often very far from the lens, I use a single strobe and lay it pretty much right down on the port of the housing. Since I’m usually only shooting tight shots of reef dwellers, it is a standardization technique that serves me well.

I should also say that it is not just the camera that gets the shots. The guides I work with in the Coral Triangle are very much a part of the process these days. Their skills at finding new fish or identifying behaviors are constantly improving, and sometimes when I go back to a destination after a year or two they are almost beside themselves with their excitement over the new things they’ve discovered to show me.

SF: Have you always supported yourself with your underwater photography?

RS: No, that was never my intention. I’m a stonemason by trade, running a family business. This always allowed me to manipulate my working days so I could leave for a month at a time, which of course I did several times a year over these past decades.

When I was recovering from my accident I got an incredible yearning to travel. This was even before I got serious about underwater photography, and I traveled all through Southeast Asia and into China back when Mao Zedong was in power. Field trips were always part of my life, and I suppose that got in the way of ever having a wife or family. But to me it seemed the adventure of travel was more important than cuddles.

Over the years I began to accumulate more and more photographs, and my archive became quite extensive. That’s probably why I got into publishing books. I’ve now done 13 of them, and Colours of the Reef was by far my most ambitious undertaking. I took 95 percent of the photos myself, which is quite a project in and of itself when you consider that there are almost 7,000 photos in the book. For the images I didn’t have, I just picked up the phone and called one of my photographer friends. In general we all do the same kind of work, but they might have a different take on a particular subject. Peter Parks, for example, does photomicrography, while Richard Pyle is willing to go to extreme depths and therefore encounters species I never would. Sometimes one of us will just happen to see something none of the rest ever have — and get an amazing picture of it as well. With friends like Ned DeLoach and Gerry Allen, the unusual is usual, and the unseen is seen.

I designed the book myself, and I self-published it. There are only 900 copies in existence, and I must say I’m really quite proud of the way it turned out. We used really good paper, and it is very well printed and bound. My friend, photographer Mike McCoy, did all the computer work, and it took us two and a half years to put it all together — well, that and the 50 years of shooting that came before I ever designed the first page.

SF: With 7,000 photos and a five-decade body of work, is there a particular photo that stands out as perhaps your favorite?

RS: I have one I’m really fond of, and while I can’t say any single shot is my all-time favorite, my spawning boxfish might be the one I worked hardest to get and kind of illustrates the lengths I sometimes have to go to get a new species or behavior recorded these days.

I’d heard through the ichthyologist grapevine that scientists had seen boxfish spawning at a particular area in Japan. I wanted to be the first photographer to capture that behavior, so I set out to learn more about it by going there. While on location I saw that the boxfish would begin a mating ritual at around dusk in this one particular area. I observed the male swim to the female and give a sort of nod. That seemed to trigger a slow spiral spawn to the surface. This was fantastic, but after I looked at all my photos I couldn’t see the eggs and sperm. I later found out the water had to be 22°C for the fertilization to happen, and the year I was there the water never got above 21°C. So of course I went back the next year. It took two trips to Japan, but eventually I got my shot!

Speaking of Japan, did you know that the emperors of Japan tend to be experts on specific marine life? Hirohito was a world authority on crabs, and the current emperor, Akihito, is a goby man. He’s not a diver but has seen many, many specimens of gobies. When I was there I brought some photos of gobies, and we had a fantastic time looking at them and talking about the natural history of gobies. It was surreal, the imperial highness of Japan and me sitting on the floor in a darkened room behind my projector, immersed in a world of tiny fish.

SF: You have been diving since 1959 — 56 years now. Many who have dived for decades bemoan the degradation they see in the coral reef. Yet I hear enthusiasm in your voice when you speak of heading off to Milne Bay in Papua New Guinea or Raja Ampat in Indonesia. Clearly you aren’t jaded by familiarity. What keeps you fresh and inspired?

RS: I don’t deny that there might be global warming, overfishing and ocean acidification on a global scale. But every time I jump in the water I see things that are beautiful and things that inspire me. There is a lot of healing power in the ocean that we should not forget about.

I remember one time I was interested in seeing the diving at the western end of Sumatra. The German fish ID guru Helmut Debelius said I shouldn’t bother with it, that it was trashed with cyanide and dynamite fishing. But I went anyway and met an uneducated guy who happened to keep a daily log of water temperature there. Usually the water was around 28°C, but a cold-water inversion dropped it to 18°C, and it stayed that way for eight months. Corals can get damaged from bleaching due to warm water, but excessive cold can stress them, too. When the water warmed up, the reef came back to life. It took 15 years, but this stretch of reef is absolutely gorgeous today. I think I have seen too much of the beauty and resilience of coral reefs to be a doom and gloom guy.

Take the crown-of-thorns sea star as another example. In the 1960s these were seen as a desperate peril to the Great Barrier Reef. Divers were hired to go pluck them from the sea and bury them ashore. But then a geologist got a grant to study them, and he determined that they had a unique spicule that would show up in the fossil record. He wanted to know if crown-of-thorns infestations had ever raged over the Great Barrier Reef before. He did core samples into the bedrock over a 10-year period. He sampled the inner reef and outer reef along the entire stretch of the Great Barrier Reef. Using an electron microscope, he found that over a 90,000-year span there were almost always crown-of-thorns sea stars on the reef. When conditions are right they breed like hell.

I guess that isn’t much reassurance when crown-of-thorns start to decimate your favorite reef or invasive lionfish eat or outcompete native Caribbean species. But taking a longer view of history and geology leaves me optimistic. The coral reef is a place of magic and wonder, and I cherish the time I’ve spent on it. I love taking new photos, but for me it’s about the hunt as much as it is about the capture.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2015