The new captain jumped from the deck fully dressed and sprinted through the water. The former lifeguard kept his eyes on his victim as he headed straight for the couple swimming between their anchored sportfishing boat and the beach. “I think he thinks you’re drowning,” the husband said to his wife. They had been splashing each other, and she had screamed, but now they were just standing neck-deep on the sand bar.

“We’re fine, what is he doing?” she asked, a little annoyed. “We’re fine!” the husband yelled, waving him off, but the captain kept swimming hard.

“Move!” he barked as he sprinted between the stunned couple. Directly behind them, not 10 feet away, their 9-year-old daughter was drowning. Safely above the surface in the arms of the captain, she burst into tears and cried, “Daddy!”

How did this captain know from 50 feet away what the father couldn’t recognize from just 10 feet? Drowning is not the violent, splashing call for help that most people expect. Experts had trained the captain to recognize drowning, and he could draw on years of experience. The father, on the other hand, had learned what drowning looks like by watching television.

If you spend time on or near the water, then you should make sure that you and your crew know what to look for whenever people enter the water. Until the daughter tearfully cried out for her daddy after the captain rescued her, she hadn’t made a sound.

As a former U.S. Coast Guard rescue swimmer, I wasn’t surprised at all by this story. Drowning is almost always a deceptively quiet event. The waving, splashing and yelling that dramatic conditioning from television shows us rarely happens in real life.

The instinctive drowning response (IDR), named by Francesco A. Pia, Ph.D., is what people do to avoid actual or perceived suffocation in the water. It does not look like what most people expect. There is very little splashing, no waving and no yelling or calls for help of any kind. To get an idea of just how quiet and undramatic drowning can appear from the surface, consider this: It is the second-leading cause of accidental death in children age 15 and under, just behind vehicle accidents. Of the approximately 750 children who will drown next year, about 375 of them will do so within 25 yards of a parent or other adult. In 10 percent of those drownings, the adult will watch but have no idea it is happening.

Drowning does not look like what we’re conditioned to think of as drowning. In an article in the Fall 2006 issue of the U.S. Coast Guard Search and Rescue’s On Scene journal, Pia described the instinctive drowning response as follows:

- Except in rare circumstances, drowning people are physiologically unable to call out for help. The respiratory system was designed for breathing. Speech is the secondary or overlaid function. Breathing must be fulfilled before speech occurs.

- Drowning people’s mouths alternately sink below and reappear above the surface of the water. The mouths of drowning people are not above the surface of the water long enough for them to exhale, inhale and call out for help. When the drowning people’s mouths are above the surface, they exhale and inhale quickly as their mouths start to sink below the surface of the water.

- Drowning people cannot wave for help. Nature instinctively forces them to extend their arms laterally and press down on the water’s surface. Pressing down on the surface of the water permits drowning people to leverage their bodies so they can lift their mouths out of the water to breathe.

- Throughout the instinctive drowning response, drowning people cannot voluntarily control their arm movements. Physiologically, drowning people who are struggling on the surface of the water cannot stop drowning and perform voluntary movements such as waving for help, moving toward a rescuer or reaching out for a piece of rescue equipment.

- From beginning to end of the instinctive drowning response, people’s bodies remain upright in the water with no evidence of a supporting kick. Unless rescued by a trained lifeguard, these drowning people can only struggle on the surface of the water from 20 to 60 seconds before submersion occurs.

This doesn’t mean that a person who is thrashing and yelling for help isn’t in real trouble — they are experiencing aquatic distress. Not always present before the IDR, aquatic distress doesn’t last long, but unlike true drowning, these victims can still assist in their rescue. They can grab throw rings or lifelines, for example.

Look for these other signs of drowning when people are in the water:

- head low in the water, mouth at water level

- head tilted back with mouth open

- eyes glassy and empty, unable to focus

- eyes closed

- hair over forehead or eyes

- not using legs — vertical position

- hyperventilating or gasping

- trying to swim in a particular direction but not making headway

- trying to roll over on the back

- appear to be climbing an invisible ladder

If a crew member falls overboard and everything looks OK, don’t be too sure. They may look like they are treading water and looking up at the deck. One way to be sure is to ask them, “Are you OK?” If they can answer at all, they probably are OK. If they return a blank stare, you may have fewer than 30 seconds to get to them. Parents should know that children playing in the water make noise. When they are quiet, get to them and find out why. Sometimes the most common indication that someone is drowning is that they don’t look like they’re drowning.

Explore More

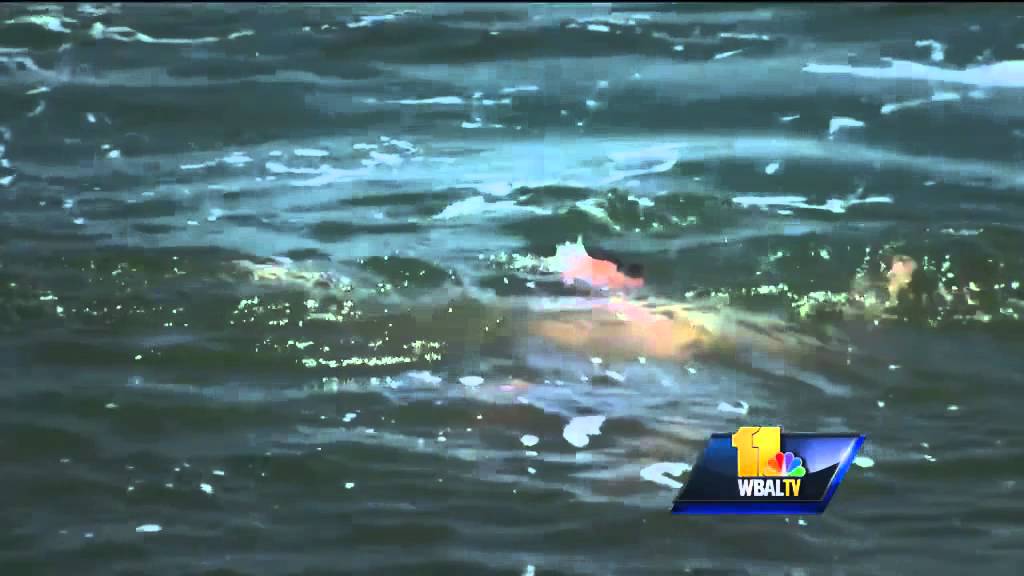

Watch these videos to learn how to recognize the signs of drowning.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2020