I almost failed my dive instructor examination — all because of a misunderstood hand signal.

I was supposed to demonstrate the controlled emergency swimming ascent skill in the pool. The examiner had briefed the skill on the pool deck, and I knew what he expected. It should have been no problem at all. He pointed to one spot at the bottom of the pool where I should start and another spot where I should finish. Then he gave me an “OK” signal, but I didn’t recognize the signal he gave me as meaning “OK,” so I never started. I just looked at him somewhat quizzically. He repeated his instructions, and finally it dawned on me what he wanted. (It is entirely possible I might have been a little nervous, too.)

I learned from a discussion afterward that he was a cave and technical diver. He preferred to use a closed fist as an OK signal rather than the more traditional open hand with the thumb and forefinger coming together in a circle. I’ve never forgotten that moment from more than a decade ago as an example of how difficult communication by hand signals can be. Even when everyone in the water knows what they are doing and what they want, if you’re not speaking the same language it’s all just a lot of hand waving.

Dialects

Divers are taught basic hand signals in their beginning dive courses, and most of those signals look the same regardless of where you learned to dive or which training agency offered the certification. But in the same way Spanish is spoken differently in Argentina than in Mexico, and English is different between New Zealand and the United States, regional variations show up in hand signals used in diving.

Technical divers, for example, develop their own hand signals, or versions of hand signals as in the “OK” example mentioned earlier, to meet the needs of their diving environment. Cave divers don’t generally have to look for a dive boat, for example, and rarely use compasses, but they do have to communicate about running lines, watching for silt and deciding which path to take while exploring.

Divers who are accustomed to diving in low visibility or using gloves all the time have to adapt their hand signals to be seen and understood in these situations. Underwater photographers and scientific divers likewise make adjustments for their circumstances. If you always have a camera or a tool in one hand, it can be a challenge to give two-handed signals. These divers develop one-handed variations of basic signals to effectively communicate with their buddies. Out of habit, those divers might continue using those same signals when in other situations as well.

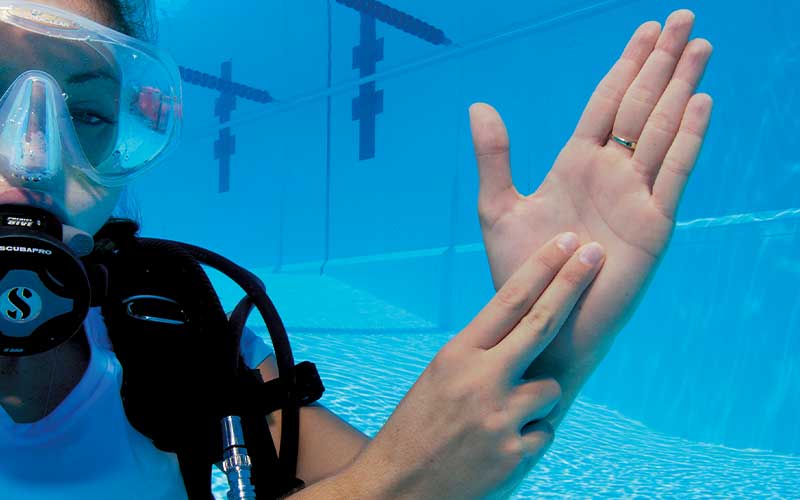

Consider all the different ways divers indicate the amount of air they have remaining in their tanks. Some use fingers pointing upward for increments of 500 psi and fingers down (or to the side) for every 100 psi after that. Others spell it out, holding up two fingers, then three fingers and then two circles to designate 2,300, for example. Some assign significance based on which hand they use to signal a number or whether the fingers displaying the numbers are held in front of the body or laid across an arm. This variety of styles leads many divemasters in their predive briefings to say, “When I point to my gauge, please just show me yours.”

Obviously, it’s best to avoid being low on air or out of air in the first place, but not everyone uses consistent signals to indicate these problems in an emergency. Many divers use a closed fist to the chest to indicate being low on air and a slashing motion across the throat to indicate being out of air. Alternatively, some divers will simply point to their buddy’s alternate air source, not to indicate that they are out of air per se, but that they need air. Others will grasp their throat, using the universal sign for choking to indicate being out of air.

Even basic signals and directions can cause confusion. Two hands cupped together often means “boat,” as in “Where is the boat?” This might be answered with a shoulder shrug, a shaken head, pointing in a particular direction or indicating a heading on a compass. But if your buddy doesn’t recognize your signal for “boat,” any of those replies might mean something totally different. Don’t underestimate the domino effect that can result from a single misunderstood signal.

Communication Topside

The solution to good communication underwater is good communication topside. Before you descend, talk to your buddy to make sure you both understand what hand signals you’ll use underwater. If you and a buddy dive together often, this isn’t much of a problem, but if you are diving with a new buddy, or if it has been a while since you dived together, it’s a great idea to take a few minutes during dive planning to go through some basic signals. An emergency situation is no time to guess what someone else is trying to tell you.

You could always learn sign language to communicate more complex thoughts, but that would require good visibility and both divers to know the language. There are many options for written communications underwater, and some technical solutions are coming onto the market, but while those are great for more detailed messages and questions, basic hand signals are too fast and too easy to fall out of general use any time soon. Hand signals, and a shared understanding of their meaning between buddies, make diving safer, less frustrating and an experience divers can enjoy together.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2011