Food had always been scarce, but it was even more so now with the Japanese occupation. Twelve-year-old Achina had taught herself to climb the coconut trees to try and augment the family’s meager larder. Her older brother, like her father, had been conscripted into the forced-labor brigades by the Japanese Army. She’d set out before dawn and by 6 a.m. had found a small stash of green coconuts missed by the others. She’d never climbed a palm tree this high before, and the breeze at the top felt stronger than down on solid ground. Achina looked out over the lagoon and saw dozens of ships all around. She reached for the first husked fruit and heard a sound like a swarm of angry bees. The sound grew louder each second; she could feel it vibrate deep in her chest and suddenly wished her father and brother were with her. She sliced off the last coconut and let it drop; the angry insect sound swelled into an almost unbearable din as U.S. naval aircraft burst into view over the vast expanse of Truk Lagoon. Achina’s life, and the lives of the Japanese occupying her island, were about to change forever.

On Feb. 17-18, 1944, in an attack code-named Operation Hailstone, American Task Force 58 pummeled the island stronghold of Truk with nearly 500 aircraft from nine aircraft carriers. By the end of the second day, more than 45 ships, nearly 300 planes and hundreds of Japanese sailors and soldiers were no longer at the emperor’s discretion. Though not the feared “Japanese Imperial Fleet,” since most frontline warships had already departed, the remaining merchant and support vessels were loaded with valuable war materials badly needed at the front. After the initial attack, American commanders decided to bypass further actions against Truk, though they continued to harass the base for the remainder of the war. With supply lines cut, conditions became even more horrid not only for the Japanese soldiers but also the Truk residents, and they remained so until the end of World War II.

In 1990, Truk was renamed Chuuk. Located approximately 3,100 miles southwest of Honolulu, Hawaii, Chuuk is a member of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), a group of more than 600 islands spread over 1 million square miles of Pacific Ocean. Yap, Kosrae and Pohnpei comprise the other states of the Federation. Chuuk is made up of about 200 of the FSM’s islands and islets; Weno, Fefan, Uman and Tonoas are the main populated islands, all nestled within Chuuk Lagoon. The outlying islands are either uninhabited or sparsely populated. As with so many FSM islands, Chuuk is volcanic in nature, and its islands vary in appearance. Some islands are steep, jagged peaks thrusting out of the water, while others take on the classic appearance of a ringed atoll.

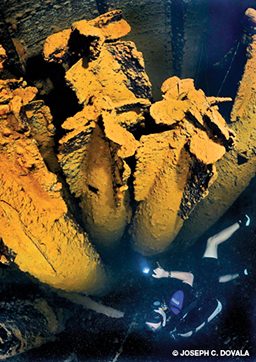

The 832-square-mile Chuuk Lagoon is one of the world’s largest and is up to 300 feet deep in places. Surrounded by a barrier reef more than 130 miles long, many mangrove-fringed islands jut from the surface. With such natural protection, it’s no wonder the Japanese chose Chuuk for their fortified base.

Despite the size and depth of the lagoon, most of the war relics are within relatively easy reach for sport divers, while others can be explored using extended-range techniques. Many of the sunken ships are concentrated in small areas, thereby eliminating the need for long boat rides. Typical recreational depths range from 40 to 110 feet for shallower wrecks like Rio de Janeiro Maru, while deeper wrecks such as Fujisan Maru lie in depth ranges of 115 to 200 feet and require additional training and equipment to dive. There’s a shipwreck for everyone at Chuuk, one reason it has become a major destination for generations of wreck-diving enthusiasts.

Chuuk is not a hop-skip-jump destination; crossing the International Date Line makes the trip feel like it takes two days. Upon arrival, there are both land-based and liveaboard dive operations. Each has its advantages. Since our plan included doing a fair amount of extended-range diving, the liveaboard option proved best for us.

Our floating hotel and dive deck was the spacious and well-equipped Truk Odyssey. The crew is expert at providing for any dive adventure, from basic recreational scuba to deep technical diving.

The morning after arrival, we received a lively but sober briefing. We were given a most important reminder. The lagoon ships are not cleaned-out vessels intended as artificial reefs; the wrecks of Chuuk are, in fact, war graves. Potentially life-threatening hazards abound on the wrecks, including entanglement. But neither the briefing nor slightly stormy weather dampened our spirits when the call of “the pool is open” came from the dive deck.

We jumped in, and the bubbles had barely cleared when the hulk of the Kiyozumi Maru materialized out of the murk. Lying on her port side 120 feet below, the 450-foot passenger cargo ship sank at the hands of a fatal torpedo hit. There is lots to see on the massive wreck, including torpedo launchers, bronze lanterns, china and various shipboard equipment. Hundreds of sea jellies intermingle with the wreck, giving it a ghostly feel.

Our next visit was the popular Yamagiri Maru. Diving depths range from 30 to 120 feet on this wreck, so divers can pick and choose an appropriate dive plan. At just under 440 feet long, she’s nearly as big as the Kiyozumi; she also lies on her port side. Interesting ship’s curiosities and beautiful coral growth cover most external surfaces. The inside holds no less: Scattered throughout the No. 5 hold are dozens of 14-inch battleship shells that never had a chance to fire on American ships. The Yamagiri‘s tight engine room is one of the spookiest of the lagoon’s attractions for two reasons: Due to the large amounts of very fine silt piled up, it looks like a set from the movie Titanic. Much more poignant is a human skull fused to a bulkhead from the ship’s fatal fire and sinking. Viewing this scene in the dark, cramped, silty engine room is a haunting reminder that these vessels went down in war — with actual people aboard.

We next dropped in on an Imperial Japanese warship. Much to the chagrin of American commanders, most of the capital ships were gone by the launch of the 1944 attack. However, a few remained in the area, and the 320-foot destroyer Fumitzuki was one of them. The Fumitzuki is a different kind of animal, sleek with a narrow beam. Hatchways and compartments are small. Though petite, there is much to see: guns, ammunition, medicine bottles, glass syringes and gas masks. One of the most amazing artifacts is a thick book written in Kanji script, which somehow remained intact underwater. Most of the ship’s superstructures have collapsed or fallen off to the seabed, and she sits low to the bottom in 125 feet of water. She’s a deep dive all the way around but well worth a visit.

One of Chuuk’s most famous wrecks, and arguably the most popular, is the Fujikawa Maru. This 437-foot freighter was the first ship to be dived by sport divers in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Its dive depths range from 40 to 115 feet, and the vessel still contains the artifacts she carried when she went down. Personal effects such as ink wells, uniforms and shoes have been found. Several Zero aircraft occupy the forward hold. The opportunity to make a close inspection of these famous airplanes alone is worth the dive. Radial engines and other aircraft parts are in jumbled piles throughout the holds. Ammunition, tools and scores of other ship’s bric-a-brac still litter the ship. The engine room has hosted tens of thousands of visitors.

As far as sport divers are concerned, one of the least-known wrecks is the Japanese fleet submarine I-169. The story of her demise is more tragic than most. The submarine was sunk not during the raids in February 1944 but nearly two months later in early April. The crew had received warning that a B-24 bomber raid was coming. The captain was ashore. As per protocol, the sub immediately submerged to wait out the air raid on the lagoon floor. It never returned to the surface. Japanese navy divers went down and found a valve still open; the control room of the sub had been flooded. The divers could hear tapping sounds coming from other compartments, and they tried to rescue the trapped sailors. But between not having the proper rescue equipment and the constant harassment from air attacks, the rescue was unsuccessful. Harbor command had the sub depth-charged to keep it out of American hands.

While much of the 336-foot-long sub is badly blown apart, a good portion of the aft section and the conning tower is still recognizable. An open hatch invites inspection. She’s deep, at 150 feet near the stern, but if you have the skills it’s well worth a visit. To my knowledge, it’s the only known diveable Japanese fleet submarine in the world.

Throughout the rest of the week we visited many a sunken Japanese transport, including the Unkai Maru, the Shinkoku Maru, the Hanakawa Maru, the Hoki Maru, the Shotan Maru, the Heian Maru, the Kensho Maru and the San Francisco Maru. The deeper wrecks such as the San Francisco and Shotan seem to be in better shape, but time has taken its toll on all. Bulkheads have collapsed, structural supports have become quite fragile, and leaking caustic materials and decaying munitions pose their own hazards. Following predive briefing instructions is extremely important. Of equal importance are local laws: All items from the tiniest floor tile to deck-mounted anti-aircraft guns are protected by the Chuukese government, and breaking the rules can result in automatic jail time and heavy fines.

After nearly seven decades under the sea, the ships and planes of Chuuk Lagoon now show their age. Nevertheless, the sunken hulks are physical reminders of a pivotal time in history. They provide a window into the lives of men who died on their decks and in their holds; to immerse yourself in the vessels of Chuuk Lagoon is to immerse yourself in the past. There may be only a few decades left of meaningful wreck diving in Chuuk, providing an urgency that warrants traveling such a great distance to visit an underwater war museum.

Historical Note

The military buildup of Truk started just after World War I, when Japan took over “administrative” duties of the Marshall, Caroline and northern Mariana islands by a League of Nations mandate. More than 100,000 Japanese military personnel settled in Micronesia during this time. Even though the mandate forbade fortification of the islands, Imperial Japan began just that, and by the late 1930s, Truk Lagoon had been turned into a formidable naval and air installation, known as “Japan’s Gibraltar of the Pacific.” Throughout the early part of World War II, virtually all Japanese naval operations were coordinated through Truk, including the attack on Pearl Harbor.

What’s in a Name?

Maru means “circle” in Japanese. One theory is that Japanese transport ships carry the designation because they were supposed to return from their missions, completing a full circle. This “circular” logic didn’t necessarily apply to their warship cousins, who were expected to fight to the death.

The Lure of the Terrestrial

Chuuk is not known for traditionally modern resort hotels. Other than sightseeing and exploring World War II artifacts, there is little to do on any of the islands. Most of the hotels are clean and have reasonably dependable power, but you’ll soon realize you’re a long way from urban in terms of amenities. The Pacific villages are simple and the roads unpredictable, depending on recent storm activity. Chuuk wreck diving can be arranged utilizing a shore-based operator or by liveaboard.

Dive In

The average air temperature in Chuuk is 80ºF; the trade winds are primarily from the northeast in December through June, though weather patterns are not as easy to forecast as they once were. The heaviest rainfall occurs in the summer months, and when the breezes are slack it can be very hot and humid. Underwater is a bit more predictable; water temperatures average in the low 80s year round, and visibility ranges from 50 to well more than 100 feet. It’s important to note that because of deeper depths and other hazards, diving the wrecks of Chuuk may require additional planning and training. Stay safe: Be sure to do your research, and do not dive outside your training and experience. For more information, visit www.fsmgov.org.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2011