It all started out on a very positive note. It was a slick, calm day as we were cruising out to the dive site when the captain shouted out, “Dolphins to port!”

Now, as exciting as the idea of swimming with dolphins might be, rarely does it actually happen. Dolphins tend to move fairly quickly, and by the time a group of divers mobilizes and jumps in the water, especially with cameras in their hands, the pod tends to be long gone.

But these dolphins seemed to be different. They were lazing about on the surface; there was no downside to giving it a try, or so we all thought.

Our group of 16 avid underwater photographers went into overdrive getting ready to dive, suiting up and checking cameras. No one was a rookie. In fact, the least experienced diver on board probably had 1,200 dives under his weight belt. But familiarity breeds neglect, and one diver, Franco, neglected to check his air.

Well, it wasn’t that he actually failed to check his air. He checked it. His submersible pressure gauge showed a healthy 3,250-psi fill, and when he took a breath from his regulator at the surface just before jumping in the water, it delivered.

Here’s where the situation came unglued. He was diving a 32-percent nitrox blend, and the boat’s analyzer sampled gas at the regulator mouthpiece, not the tank yoke. So when the divemaster cranked the valve to check the gas via the regulator, it was left only partially open.

Unfortunately, Franco didn’t confirm his tank valve was cranked completely open before he jumped in. After all, his regulator breathed just fine at the surface, and his pressure gauge confirmed a full tank. While the boat’s normal protocol was to have a divemaster on the dive platform confirm that valves were wide open, in the melee to jump in the water for the dolphin encounter, Franco’s valve was missed.

True to expectations, the dolphins moved away from the dive group but remained tantalizingly close. The sand bottom was about 75 feet deep, and the divers collectively drifted into deeper water, pursuing the gray phantoms just beyond the edge of visibility. Buddy teams separated, and Franco was alone when he had difficulty drawing air from his primary regulator. A quick check of his safe second confirmed trouble brewing, and when he toggled the power inflator on his BCD, his pressure gauge pegged at zero. Franco assumed he had no other options and began a free ascent.

He did as he was trained and exhaled all the way to the surface to avoid embolizing. He had not been down long enough for decompression sickness to be much of a hazard, but 50 feet is a long swim on a single, paltry breath. Franco clawed his way upward, surfacing near the boat. The crew on board saw him in distress and quickly pulled him aboard, but already his skin was a frighteningly blue color, and he coughed up frothy spittle.

By the time I got back on board, Franco had vomited plenty of seawater, but he was lying down, receiving oxygen from the boat’s DAN® oxygen unit and being attended to by crew; fortunately, a doctor and nurse were among the passengers. The rescue and first aid were successful, and Franco was back diving the next day. However, we were all a bit more cautious, and I hope we will never forget to make sure our tank valves are completely open before entering the water.

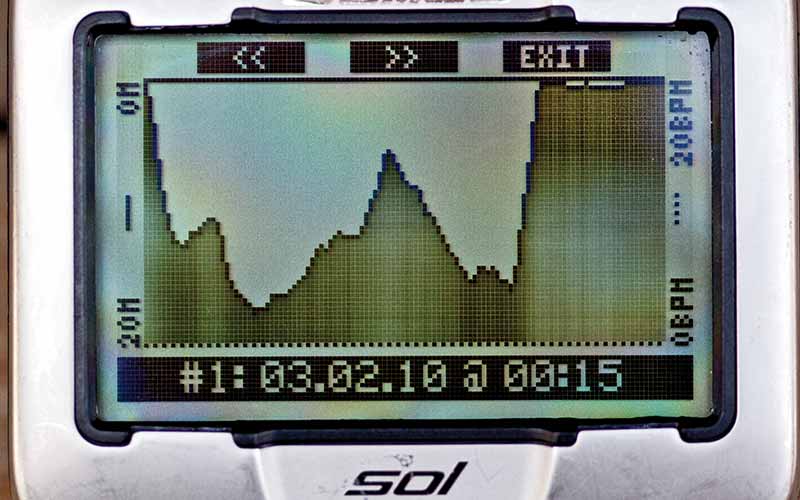

After Franco recovered and inspected his gear, he confirmed the problem. With the tank valve fully open, he still had 2,175 psi in his cylinder.

While boat crews typically double-check tank valves, none of us who saw Franco puking seawater and fighting for those critical breaths of oxygen will ever again leave this detail to chance.

Don’t let the high level of service you receive from “concierge” dive operators insulate you from responsibility for your own safety.

© Alert Diver — Q2 Spring 2010