Jacques Cousteau called it the corridor of marvels; for European divers it is simply our favorite destination. More of us dive here than anywhere else. It is the nearest warm water to us, but its lure is about much more than convenience. The Red Sea is a classic dive destination — a must-see no matter where in the world you live.

Variety is the Red Sea’s trump card. The place offers such diversity of high-quality underwater adventures that “Red Sea diving” means something different to everyone. It is a hugely popular destination that offers classic reef diving, coral caverns, shark dives, big wrecks, tech diving, freediving and even critter-rich muck diving. With multiple resort hubs split between the main Egyptian coast and the Sinai Peninsula combined with a variety of liveaboard itineraries, there are endless ways to do it. In short, I have a lot to shoehorn into this article.

Five Star Jackson

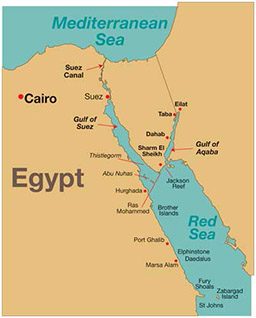

Throaty Arabic shouting curdles amidst diesel smoke in the chaotic Travco Marina in Sharm El Sheikh. We swiftly file through the melee and step onto the haven that is our dive boat. Lots of divers means lots of diving infrastructure; the downside is that there are more peaceful places to start your day. Soon we’re out of port and heading north to the marvels of the Strait of Tiran. Dive boats in Egypt tend to be large, white affairs with a saloon inside and a sundeck up top, which makes the typical two-tank trips very spacious and comfortable.

At Jackson Reef I giant stride from the dusty desert atmosphere, and I’m in paradise. The first dive of any Red Sea trip is always magical because of the intensity of the transition from the barren landscape to the reef’s richness. This reef just screams Red Sea to me: the vertical walls are hung with soft corals, most in characteristic bright red, and dancing around them in the gentle current are thousands of anthias, which always seem much bigger and more purely orange in the Red Sea. Set against the bright, almost electric-blue water, it is a stunning and specific color palette that is unmistakably Egypt. There are places with greater reef diversity or with a wider range of colors and shapes that contribute to the scene, but to my eyes it is the compositional simplicity and intensity of these primary hues that makes these reefs the most beautiful in the world.

We drift past scores of reef fish to see a hawksbill turtle munching on yellow soft corals, a big school of green unicornfish and a tartan longnose hawkfish in a huge seafan. While we’re floating along on our safety stop, a scalloped hammerhead cruises past, effortlessly moving against the current 30 feet below us. The far side of Jackson Reef is well known for schooling hammerheads, and liveaboards often make a dawn dive out into the blue in an attempt to see them. It is a bonus to see one near the coral garden.

Poles Apart

Tiran is the farthest north that liveaboards can go in Egypt, and its reefs are quite a bit different than those 400 miles away in Egypt’s “deep south.” St John’s Reef is a collection of shallower sites incorporating coral pinnacles and extensive caverns. The pinnacles are a fabulous spot for reef life; I particularly like late-afternoon dives here when the anemones begin to close and offer up the chance to photograph the resident Red Sea anemonefish against their Ferrari-red anemone skirts. The shallow caverns of St John’s also captivate photographers, who regularly spend hours there trying obsessively to capture perfect beams of sunlight. I never manage it.

There is plenty of diving north of Tiran, almost all of it shore diving. Rather than owning boats, dive centers load customers into jeeps and gear into trailers and head off road. Groups are usually small, dive sites are quiet, and trips are of good value, but shore diving requires a little more effort than falling in from a boat.

A two-hour drive north from Sharm El Sheikh is the town of Dahab, which offers a range of shore dives from shallow coral gardens to the enigmatic Blue Hole. Away from the bright lights of Sharm, the Bedouin culture of the Sinai shines. Dahab is a chilled-out place and a hub for both freediving and technical diving. The Blue Hole is a great dive, but a swim through its deep arch should be undertaken only by trained and prepared technical divers. The tunnel is at 180 feet and much longer than it appears from the surface; there’s often a current flowing in as well. When accidents happen here, they are not small ones.

Little Treasures

The relaxed nature of Dahab is echoed in the resort towns farther to the north, Nuweiba and Taba, and it continues underwater with many shallow sites ideal for slow explorations. Seahorses, frogfish, nudibranchs, snake eels, seamoths, ghostpipefish and mimic octopuses are more often associated with exotic spots in southeast Asia, but they can all be found regularly in the upper reaches of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Surprisingly, it was only after muck diving became popular in Asia that divers really started to explore similar habitats in Egypt and intentionally hunt for critters. Once they did, they found many of the same Indo-Pacific species here. If you are a photographer or naturalist who enjoys long, puttering macro dives, you’ll find your Red Sea home in the quiet resort towns of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Another attraction of the shore is the great Red Sea staple: lionfish. Jetties, in particular, always seem to have a resident pride. They’re at their most magnificent when a dozen or more are pack hunting for silversides or glassfish just before dusk.

Red Sea lionfish always seem bigger and bolder than those in other places; in fact it is common for Red Sea lionfish to charge right up to you, warning you to stay off their patch. A fish that swims directly at your lens makes for great photos. At night they follow divers’ torch beams around the reef, picking off fish dazzled by the light.

The jetty in Nuweiba is a classic spot for lionfish reflections, but my abiding memory from a February visit is bitter cold. For the uninitiated (and every visitor needs this spelled out to them), the Red Sea may have coral reefs, but it is very seasonal. At the height of summer the water hits 86°F, and most people dive in bathing suits. But in February and March, with a biting wind and 66°F water, it is completely different — even when the sun is shining. Many Europeans bring drysuits in this season. Foolishly, I didn’t, and while it snowed on the hills in Jordan I froze on a coral reef less than 50 miles away.

Theater of Dreams

Coral reefs are almost exclusively tropical, so the 20-degree temperature cycle in the Red Sea is unusual. It doesn’t just affect diving attire, it drives big changes on the reef, too. Normally, reef fish mate throughout the year, so divers don’t always notice it. In the Red Sea, however, there is a definite spawning season. When the water warms up, the whole place comes alive biologically.

Summer is my favorite time of year to visit, and I’ve logged more than 20 liveaboard weeks here in the June/July window. You don’t need to be a fish geek to appreciate it either; this is biology on a grand scale.

We’re at the legendary Ras Mohammed. It’s right at the tip of Sinai, and it’s the crossroads of the three arms of the Red Sea. The reef here is a spectacular formation with two big pinnacles just yards from shore and a wall that starts at the surface and drops precipitously to a couple of thousand feet. The wall is covered with red and purple soft corals, streamed over by clouds of anthias and populated by reef fish of every kind. There is great macro here, too; I always spy loads of nudibranchs. But today the real attractions lie out in the blue.

Jutting out into the open Red Sea makes Ras Mohammed an irresistible fish-spawning site, and today, the day after the June new moon, it is heaving. There is a steady current pushing me down the face of the wall and keeping the fish in tight groups, neatly segregated by species. First up are a group of 30 large batfish, but I ignore them instantly because behind them is a huge block of bohar snappers the size of a house. The large individuals are more than two feet long, and they are packed together so tightly it almost gets dark as I drift through the middle. At one point I am suspended in a sphere of clear blue water with a moving wall of big fish on every side. Breathtaking.

Below snappers, pairs of bigeye trevallies are courting; the slightly smaller males have turned from silver to black as they swim in synchrony below the females. I drift on and spot a room-sized school of large unicornfish below me. I also see schools of blueline emperors, black snappers, longnose parrotfish, giant trevally, more batfish and perhaps most impressive, a huge swirl of barracuda that materializes from the blue. I move toward them, but my ears warn me that the fish are luring me deeper and deeper, and I turn back to the reef.

This is truly one of the best dives of my life, and it is not even my best dive at Ras Mohammed. Here I’ve watched silky sharks stalking barracudas, a napoleon wrasse fight a titan triggerfish to steal its eggs, a manta burst through schooling snappers and even a pod of dolphins hunting.

This is my favorite dive site in the world, and we’re less than an hour from Sharm. I know it is sounds cooler to name somewhere remote, but Ras Mohammed, filled with the summer schools, is one of the world’s great wildlife spectacles. A big reason I love the place is that so many people get to experience it.

Winter Wonderland

While summer equals spawning, winter means sharks. Cooler waters always seem to increase shark sightings. Like most regions, the Red Sea’s shark populations are not what they once were, but on remote reefs sightings are usually reliable with an impressive variety of species: grey reef sharks, reef whitetips, leopards, tigers, oceanic whitetips, hammerheads and even thresher sharks.

Offshore reefs such as Brothers, Elphinstone and Daedalus are the most sharky and tend to be the exclusive domain of liveaboards. The liveaboard-versus-shore-based debate is waged as hotly in Egypt as in many destinations. In addition to the usual arguments, Egyptian liveaboards allow you to escape the heat of the land and avoid the tourist traps, but you miss out on the available après-dive options. While anchorages are well protected, the open Red Sea can be rough. For comfort, most of the best liveaboards today are big boats that accommodate 20 divers or even more. This helps passengers avoid seasickness, but it makes solitude underwater harder to come by.

It’s mid-November at Elphinstone Reef, and I am hoping to see another Red Sea icon: the oceanic whitetip shark. This species was once widespread throughout the warm parts of the world’s oceans, but it has been fished near the point of extinction. Elphinstone is one of the few remaining places to see them. Here and now, at the peak of the season, you can see more than 20 individuals in a day. The reef is pretty, too, and shaped a bit like a loaf of bread, with vertical walls, soft corals and schools of fish. But I am distracted, scanning the blue for those unmistakable silhouettes.

The oceanics don’t arrive immediately; in fact we’re on our way up when we see the first. And the best encounters come once we’re back under the boat. These don’t behave like other sharks; they just swim right up and check you out. Their confidence continues to grow as our group withers and people climb up the ladders with surprising speed. The action is truly exhilarating by the end.

A Troubled Past … And Present?

A question that American friends understandably ask me is, “How safe is the Red Sea?” It seems there is bad news from the Middle East almost daily, and there have been high-profile terrorist attacks in the past. Personally I’ve been there many times and never had or heard about a problem with either crime or security. European divers and vacationers in general (because the Red Sea attracts far more than divers) continue to visit. Egyptian authorities have done much to protect tourism and tourists, including restricting public access to most tourist areas. Out on a dive boat, and particularly on a liveaboard, you are even farther from risk.

Wreck Heaven

But not all ships that passed through the region avoided trouble. In 1869 the Suez Canal was opened, and this transformed the Red Sea into a major navigation highway. It will come as no surprise that lots of ships and lots of reefs in a narrow sea means lots of wrecks.

I am at Abu Nuhas reef, a small triangular chunk of coral that sticks out just south of the Gulf of Suez. This reef has claimed at least seven ships, and four of them lie along the reef’s north face: the Giannis D, Carnatic, Chrisoula K and Kimon M. All four are big cargo vessels; each has a distinct character, and they’re all mostly intact, covered in life and in perfect diving depths.

You can reach Abu Nuhas either by liveaboard or by day boat from Hurghada. This morning we’re heading to the 300-foot-long and 150-year-old Carnatic, a steam-and-sail schooner that sank here with a cargo that included a fortune in gold coins. After being down for so long, the real treasure of this wreck is the amount of marine life. The outside is plastered in coral, but the ship’s elegant lines are still clearly visible. Inside I find an obliging school of glassfish being hunted by redmouth groupers.

Heading back to the liveaboard, our zodiac is joined by a pod of bottlenose dolphins. Our guide indicates that we should jump in, and we don’t need to be told twice. It is a magical 15 minutes and a surprisingly regular occurrence, thanks to a semiresident pod at Abu Nuhas.

Each wreck is a great dive, and debating favorites is common dinner conversation on liveaboards. I have seen many divers come to Abu Nuhas claiming to not enjoy wrecks and leave as addicts. The Red Sea has so many wrecks that some liveaboards offer itineraries dedicated entirely to wreck diving.

Underwater Museum

It is impossible to discuss Red Sea wrecks without including the famous HMS Thistlegorm, which is less a wreck and more a World War II time capsule. The Thistlegorm was a British supply ship that was bringing military equipment to troops in North Africa when it was sunk by German bombers.

It’s more than 400 feet long, and it sits largely complete and upright in 100 feet of water with the top of the bridge at 35 feet. Being something of an oasis on a flat, sandy seabed, it attracts an abundance of marine life that includes lots of schooling fish such as fusiliers and batfish and plenty of soft coral. I have even seen nudibranchs crawling over the motorbikes. Yes, motorbikes! The real lure of the Thistlegorm isn’t the wreck but what it was carrying: trucks and armored troop carriers, two locomotives, boxes of rifles and perhaps most interestingly, scores of motorbikes.

We’ve travelled on to the Thistlegorm from Abu Nuhas, and we discover we’re not alone. This is one of the world’s most popular dive sites, accessible by liveaboards as well as day boats from Sharm El Sheikh (after a 4 a.m. start). It is part and parcel of Red Sea diving that there will always other boats around, but guides are usually skilled at finding you solitude underwater, even if your boat is moored amid others. And most of the dive sites are extensive reefs or massive wrecks, so there is usually room for everyone.

The Red Sea is a place where lots people first try scuba, and a great many keep coming back. Underwater it offers a lifetime of adventures and so many flavors of diving that it continues to satisfy the palette even as one’s tastes in diving change and mature. After your first trip you will find the Red Sea unforgettable, and such is the variety of diving that it will always keep you enthralled.

Traveling to the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a 1,400-mile-long, narrow, and more than 7000-foot-deep offshoot of the Indian Ocean that divides the continents of Africa and Asia. Surrounded by desert, it is bathed in sunshine for 365 days of the year. Despite reaching a latitude about as far north as Orlando, extensive coral reefs thrive. Its comparatively northerly location and its isolation from the rest of the Indo-Pacific give it a distinct character among coral seas: It is strongly seasonal and has a high number of endemic species.

The Red Sea is not a short hop from North America; that combined with the jet lag makes it a two-week destination. But it doesn’t have to be two weeks of diving. It is actually very simple to combine a week of Red Sea diving with either a vacation in Europe or an extended stay in Egypt — perhaps a week of Egyptology along the Nile.

Editor’s Note:The security situation in Egypt has been subject to change in recent months. Before planning travel, consider checking the U.S. State Department’s website or a similar resource.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2013