I’m going to see an oral surgeon next week for dental implants; will I ever be able to dive again?

A dental implant is a titanium post or frame that’s surgically placed in the jawbone. An implant replaces a natural tooth root and provides a base for mounting replacement teeth or a bridge. There are multiple steps in the process of dental implantation, and each step has its own restrictions on diving. The steps can be completed simultaneously as a same-day implant or extended over time. Your dentist or oral surgeon is your best resource, but the following information may be helpful. In general, diving is not recommended until all healing is complete, the implant has had adequate integration time and the appropriate dental restoration is in place.

The initial step is extraction of a damaged tooth. At the time of the extraction, several things may happen. A bone matrix (bone graft) may be placed in the socket to provide a suitable site for the future implant. Placement of grafting material depends on the site in the jaw and the density and thickness of the surrounding bone. Alternatively, the tooth could be extracted and the socket allowed to heal naturally. Or the implant might be placed at the time of the extraction.

The placement of the implant is the most critical step. Your implant specialist will drill a precise hole into the bone and screw in a threaded titanium post. Following this procedure, you will need to avoid diving for an extended period to allow osseointegration of the implant.

Fusion of the titanium implant and the surrounding bone is crucial to success. Anything that interferes with this osseointegration, including micromovement of the implant, infection, etc., can cause the implant to fail. There is no specific research on dental implants and diving, and dentists’ opinions about time out of the water vary. Some will suggest a minimum of three months, while others advise six to 12 months before resuming diving (or other activities that put stress on the teeth). Please follow your dentist’s recommendations about healing time. While some dentists may not know diving, they should have a recommendation about how long to avoid dental stress.

The final steps are relatively simple and will not appreciably affect diving. The inserted titanium implant is topped with a small post. The dentist will access the post and place the final appliance. This may be a crown, an anchoring point for a bridge or a similar reconstruction. If the osseointegration has already occurred, diving can generally be resumed after a few weeks to allow the gums to heal.

Once the final device or crown is in place, the implant can be treated like any other tooth. Keep it brushed and flossed, and it should serve you well. Consider a trial run in a pool to see how the bite wings of your regulator’s mouthpiece fit the final reconstruction.

— Frances Smith, MS, DMT, EMT-P

I have a student who has a neurostimulator for back pain. What exactly is a neurostimulator, and are there any implications for diving?

Neurostimulators are surgically implanted devices that have some similarity to cardiac pacemakers. Used for chronic pain as well as other conditions ranging from gastrointestinal problems to Parkinson’s disease, they are implanted under the skin and have leads (wires) that run from the device to the areas in need of stimulation. Neurostimulators used for chronic back pain are often placed in the abdomen or upper part of the buttocks, and the leads are placed in the epidural space near the spinal cord. As with other implanted electrical devices, there are some issues divers should consider relative to both the device itself and the underlying medical condition.

An important consideration relative to the device is the pressure rating. These particular devices are often rated only to an ambient pressure of 2 atmospheres absolute (33 feet of seawater). Medtronic, one manufacturer, states that exceeding this pressure could lead to degradation of the system. Furthermore, exceeding the recommended maximum pressure could lead to changes in the way the device works or cause it to fail, which would require surgical removal and reimplantation. People with neurostimulators can determine the pressure rating of their system by reviewing in the literature provided to them the sections that address sports and other activities. They can also get information by calling the toll-free number on the device identification card and providing the serial number.

Another consideration that shouldn’t be overlooked is the underlying reason for the device. That condition must be evaluated with respect to any potential problems with diving.

— Scott Smith, EMT-P

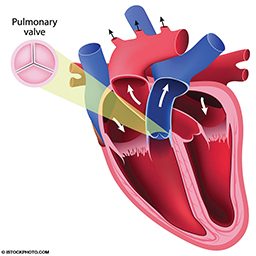

I am 48 years old and have moderate hypertension. I was diagnosed with pulmonary stenosis, which was surgically corrected. The pulmonary valve, however, is allowing some blood to leak, permitting backflow. Is this a disqualifier for scuba diving? What short-term and long-term risks are involved in diving with this medical issue?

Whether or not a medical condition disqualifies a person from diving depends on several factors, including the severity of disease and the presence of associated medical conditions. The diver must undergo a thorough evaluation by a doctor, and fitness to dive must be considered on a case-by-case basis. The general comments here are intended to provide background on pulmonary valve insufficiency and some of the associated cardiac issues that influence decisions regarding fitness to dive.

Deoxygenated blood returning from the body enters the heart before making its way to the lungs for reoxygenation. Pulmonary valve insufficiency may result in the backward flow of blood (regurgitation) into the right ventricle of the heart. Minimal or mild pulmonary insufficiency is common in many people with otherwise healthy hearts and rarely requires medical intervention. Although mild pulmonary insufficiency may not manifest with symptoms, individuals with a more severe condition may experience fatigue, shortness of breath (especially during physical exertion), exercise intolerance, fainting, palpitations or chest pain. Backflow may result from a number of medical conditions, including congenital malformation, pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary stenosis.

Pulmonary stenosis, a narrowing between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery, results in an obstruction in the flow of oxygen-poor blood from the heart to the lungs. Even after being corrected, pulmonary insufficiency may still be present. Whether or not regurgitation disqualifies someone from diving depends on the severity of regurgitation, the existence of underlying myocardial disease and especially the health and function of the right ventricle.

Factors such as age and chronic hypertension can result in thickening of the ventricle walls (hypertrophy) and loss of cardiac elasticity that reduce the heart’s ability to adapt to physiologic stress. Various factors — including immersion, exercise and cold water — shift fluid from the body’s periphery to the core and increase cardiac workload. If the muscle of the right ventricle is compromised in some way, the heart may not be able to handle these diving-associated fluid shifts.

If the leak is mild enough that symptoms are not apparent and the right ventricle is of normal size and function, it is likely that diving can be done safely. Valvular incompetence can result in increased right ventricular stress and result in hypertrophy (independent from systemic elevations in blood pressure). How the heart muscle responds to this overload depends on the severity of the condition and how long it has been present. Chronic overload can result in hypertrophy, which reduces cardiac efficiency and requires increased blood flow to the heart muscle itself. During physiologically stressful states such as immersion, exercise and extreme temperatures, the heart may not be able to meet the demands of cardiac muscle. Hypertrophic disease also increases the risk of irregular heartbeats (arrhythmia), which may lead to heart failure or unstable heart rhythms. Hypertrophic ventricles are also less able to accommodate significant fluid shifts.

Valve repair can require lifelong anticoagulant therapy, although this is more common with the aortic and mitral valves. Although the use of anticoagulants alone is not necessarily an absolute disqualifier from recreational diving, it should factor into an overall decision about one’s medical fitness to dive.

It is important to seek medical evaluation prior to diving, and it would be prudent to consult a cardiologist, who may order a cardiovascular stress test or other testing to determine cardiac function and your ability to perform at the higher levels of activity needed for diving. If you have additional questions, call the DAN Medical Information Line at +1-919-684-2948.

— Payal Razdan, MPH, EMT, and Nicholas Bird, M.D., MMM

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2016