Some divers like shallow natural reefs; others enjoy deep or technical dives. Some prefer to explore caverns and caves, while others choose the sunken treasures of shipwrecks. Whether from accidental causes or intentional sinking, shipwrecks are archaeological sites that offer amazing diving as well as a look into our past.

A common misconception is that underwater archaeology is limited to shipwrecks. While shipwrecks are the most common destinations for divers seeking to explore beyond the natural environment, they are not the only archaeological sites available to divers and researchers. Sites that feature the wreckage of aircraft, cars or trains are popular attractions, but let’s not overlook that submerged ruins, sometimes ancient, lie ready to illuminate a piece of history for visiting divers. Regardless of what is submerged or how it got there, it is part of our underwater cultural heritage.

At the 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defined underwater cultural heritage as the following:

“Underwater cultural heritage” means all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally under water, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years such as: (i) sites, structures, buildings, artifacts and human remains, together with their archaeological and natural context; (ii) vessels, aircraft, other vehicles or any part thereof, their cargo or other contents, together with their archaeological and natural context; and (iii) objects of prehistoric character.

Underwater heritage can also be more recent than 100 years. Some of the amazing World War II wrecks that divers frequent, for example, are part of our underwater heritage. Regardless of age, our underwater heritage is a nonrenewable resource and in many cases is very fragile. It is our responsibility to dive these sites in a safe, responsible and conservational manner. Whether the site is, was or may be a site for archaeological study, when we dive with an archaeological outlook, we gain further appreciation for the site, its history and cultural significance.

Archaeologists study these sites and the artifacts they contain to learn about past peoples and how they lived. Rarely do they begin working and researching a site because they first discovered it underwater. A researcher usually knows the site or wreck location or is seeking it based on other sources of information. The research typically begins in the library or on the internet.

When diving a shipwreck or another site that has cultural significance, we are usually briefed by the divemaster on the history, origin and culture that are associated with the site, so we have some context about that site and its features. If you become intrigued about the history of a given site, there are plenty of avenues to conduct your own research about the site and its origins. In the case of formal archaeological studies, extensive background research is an essential aspect of planning and preparing for an archaeological dive.

When diving a site for the first time, underwater archaeologists conduct one or a series of survey dives (depending on the size of the site) to get an overall impression of the site, its features, layout, potential hazards and other clues about the features so they can plan their subsequent dives and utilize the best methodology for surveying the site.

Underwater archaeologists look for how the feature got there, the size of any related debris field and clues about its origin and identity. If a ship sank quickly, for example, the debris field will likely be small. If a ship sinks gradually with a lot of movement, such as during a storm, the debris field can be very large. These observations and concepts are important for determining the methodology used to survey the site. During the initial survey dives, archaeologists take photographs and video and make rough sketches of the site. After the preliminary work is done, they plan the next series of dives to focus on detailed measurements, study and data collection.

The methodology used will vary based on the size, features and overall layout of the site. The techniques for this kind of work require specific training and experience to correctly and efficiently perform them. Some scuba training agencies offer specialty courses in underwater archaeology, but training in archaeological survey techniques is usually found at colleges and universities. While recreational divers may take a less rigorous approach, they can still gain a deeper appreciation for the story and legacy of a site by understanding how to appropriately treat it. Documenting and preserving underwater heritage sites are crucial for protecting their valuable history and culture and drawing a connection from the past to the present. For the dive community, taking care of these sites ensures they will be available for future generations of divers.

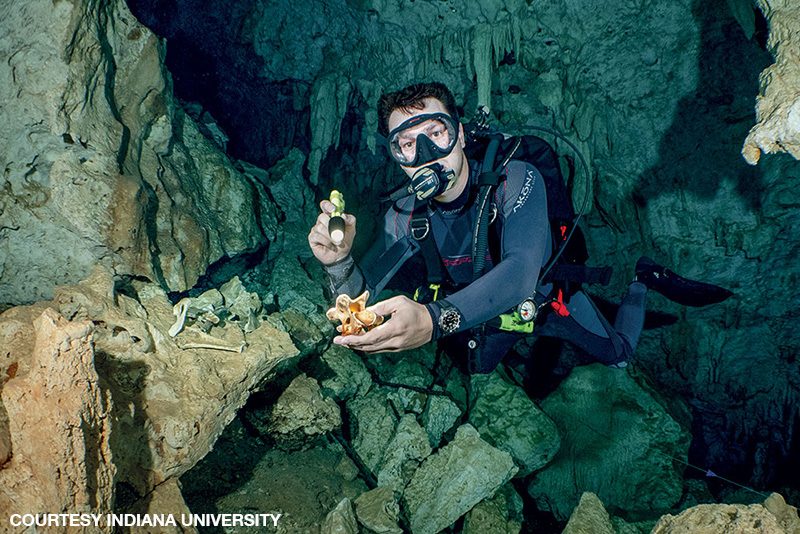

As archaeological studies continue, the primary focus is usually to record data, measurements and observations, not to recover artifacts. These nonintrusive survey methods help preserve the integrity of the site and its artifacts, which are left in place and will not be brought to the surface.

Divers should never take a souvenir from a site. This practice is not only destructive to the site but is also illegal in many cases. Removing something from a wreck or other site can cause irreparable damage to the site and potentially create a permanent loss of some of its historical and cultural significance. It could also cost the diver tens of thousands of dollars in fines and perhaps even jail time, depending on the jurisdiction and what was taken or disturbed.

Unless you have a permit to excavate or remove artifacts from a site, do not disturb, tamper with or remove any items. The excavation process needed to preserve the integrity of the artifacts for future study or museum display is often very involved, technical and expensive, and it requires resources not available to the average diver. Regardless of the laws governing an underwater archaeological site, it is the duty and responsibility of divers to respect the historical and cultural heritage as well as the environmental integrity of these sites.

Divers should also avoid cleaning any features or artifacts on a site, which can be destructive. Underwater cultural heritage sites become relatively stable in the marine environment. Sediments and biological growth, such as crustose coralline algae, cover the site with a barrier that slows the deleterious effects of saltwater, and freshwater environments have a similar process. These processes help protect the artifacts and features. Moving, removing, uncovering or cleaning these surfaces removes the protective layers and introduces higher levels of oxygen and bacteria, which accelerates the rate of decay.

Construction, erosion, dredging, treasure hunting, looting and uninformed divers taking souvenirs threaten underwater cultural heritage sites. When at heritage sites, divers should behave as if they are visiting an underwater museum and leave objects in place for future divers, remembering to “take only pictures and leave only bubbles.” The next time you are at a site with archaeological features, remember to treat it as what it is: part of our underwater heritage.

© Alert Diver — Q4 2019