“Of all the means of expression, photography is the only one that fixes forever the precise and transitory instant. We photographers deal in things that are continually vanishing, and when they have vanished, there is no contrivance on earth that can make them come back again. We cannot develop and print a memory. The writer has time to reflect. He can accept and reject, accept again; and before committing his thoughts to paper he is able to tie the several relevant elements together. There is also a period when his brain ‘forgets,’ and his subconscious works on classifying his thoughts. But for photographers, what has gone is gone forever.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson,

The Mind’s Eye: Writings on Photography and Photographers

In an era when the oceans of the world are in such distress, the Cartier-Bresson quote from 1952 regarding photography’s “decisive moment” powerfully resonates. Today many underwater photographers are ready to travel to any place on the planet where photo opportunities exist to document all that is in peril and yet remains wonderfully worthy of preservation. For politicians and industrialists who will never place their heads below the waves, the collective vision of these underwater photo enthusiasts may chip away at their rationalizations that the ocean is so vast and impervious that their avarice will not have consequences.

We photographers go to sea equipped with digital cameras, housings and strobes, hoping to bring home images that communicate an interconnected narrative between fish and reef and humankind. We have seen the diminishment of marine life populations and corals attacked by rising temperature and degraded water quality. We have seen factory fishing fleets hauling massive nets that efficiently scarify everything in their wake. We can relate to Cartier-Bresson’s observation that “when they are vanished, there is no contrivance on earth that can make them come back again.”

It is our job as underwater photographers to document the beauty and fragility of the underwater world and to share it by any means possible, such as through magazines, books and social media posts. It’s a noble cause. The queen angelfish from the Cayman Islands, the humpback whales from Tonga or the great white sharks from Guadalupe Island, Mexico, can’t speak for themselves. Underwater photographers can be their voice and fight their fight.

As part of the 2019 Nature’s Best Photography Windland Smith Rice International Awards annual competition, the Ocean Views category honors those photographers whose skill and creative vision have captured a frozen moment in time that can bring attention to both the bounty and fragility of the marine ecosystems found in and near our underwater world.

— Stephen Frink

WINNER

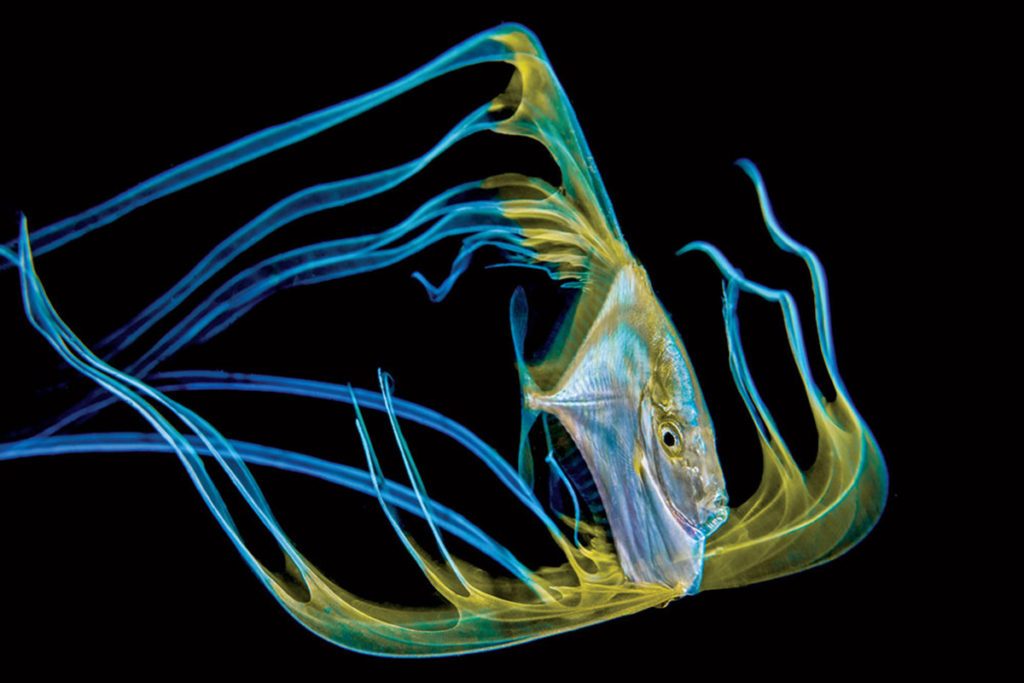

African Pompano

Anilao, Batangas, Philippines

By Songda Cai

During my blackwater diving I’ve seen juvenile African pompano multiple times, but this individual captured my interest, with its filaments seemingly darkened and a smudge of black along the trail of blue. I followed its movements for a while, watching and waiting for the right shot to show off its beauty and its silhouette wonderfully contrasted against the dark. I used a slow shutter speed to capture the trails it left behind in its wake.

(Nikon D850, Nikkor 60mm f/2.8G ED micro lens, 1/6 sec, f/25, ISO 250, Seacam Seaflash 150D strobes (2), Seacam housing; songdacai.com)

HIGHLY HONORED IMAGES

Marine Iguana

Puerto Villamil, Isabela Island, Galápagos

By Marek Jackowski

As the temperature cooled down after a very hot and humid day, I was walking on the beach near Puerto Villamil on Isabela Island and enjoying a nice breeze from the ocean. A few motionless marine iguanas were resting on lava rocks. They looked so calm and otherworldly as the beautiful sunset created magical scenery.

(Nikon D5, Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8G ED VR II lens at 190mm, 1/100 sec, f/5.6, ISO 320; marekjackowski.net)

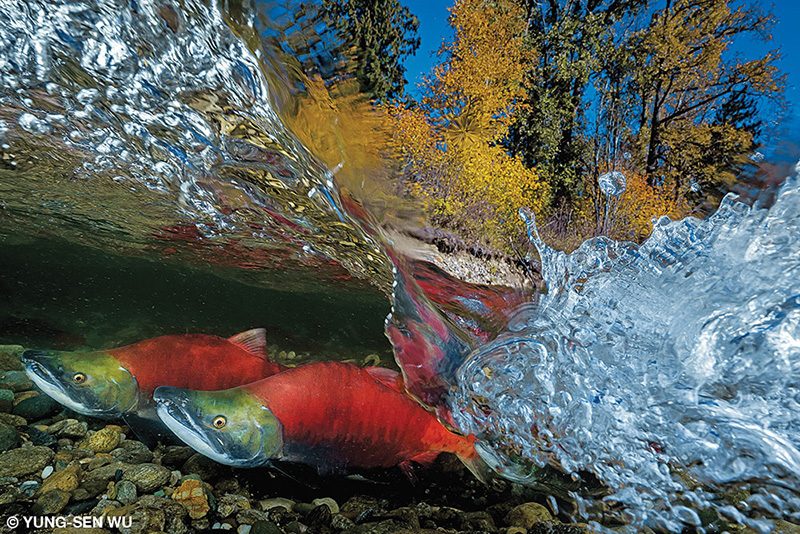

Pacific Red Sockeye Salmon

Adams River, British Columbia, Canada

By Yung-sen Wu

Pacific salmon come to the west coast of Canada from the distant sea every autumn to return to their birthplace in an inland river to spawn. Along with sockeye (red), other Pacific salmon include coho (silver), chum (keta), humpback (pink) and chinook (king). Migrating salmon don’t eat or drink water during their exhausting three-month, 500-mile journey home. Completing the most important mission of their life, the salmon die after spawning and fertilization.

(Sony a7R III, Sony FE 12-24mm lens at 13mm, 1/160 sec, f/16, ISO 200, Seacam Seaflash 150D strobes (2), Seacam silver housing)

Manta Ray

Galápagos Islands

By Jenny Stock

While taking photographs meant to captivate and inspire, photographers occasionally become part of the story. During a dive in Galápagos I witnessed this manta swimming up through the water column. In anticipation, I switched off my strobes and waited for the manta to rise up further and block the sun to create a dramatic backlit silhouetted image. As I framed my shot I realized that my dive buddy, who was capturing her own image of the manta, would make a beautiful addition to the frame, thus telling the story of how we are constantly chasing our dreams in photography.

(Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, 15mm lens, 1/800 sec, f/11, ISO 250, Nauticam housing; instagram.com/jenniferjostock)

Australian Sea Lion

Essex Rocks Island, Jurien Bay Marine Park, Western Australia

By Jenny Stock

Sea lions are the most inquisitive animals I have encountered underwater. Unfortunately, these playful characters are classified as an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to often becoming the victims of bycatch or entangling themselves in marine debris and pollution. Powered by their flippered feet, these big-eyed frisky mammals performed aquabatics left and right of me, reaching speeds of up to 35 miles per hour. When they tired of me, I could regain their attention by spinning in the water — a behavior they seemed to delight in and would show their enjoyment by mimicking me in response.

(Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon EF16-35mm f/2.8L III USM lens at 17mm, 1/200 sec, f/18, ISO 400, Inon Z-240 strobes (2), Nauticam housing; Instagram.com/jenniferjostock)

Butterfly Blenny

Noli, Savona, Italy

By Aldo Costa

After looking for a butterfly blenny (Blennius ocellaris) for many years, I learned that divers had seen them in the depths near Noli, Italy. I immediately went there and made three long dives to scour the infinite sandy bottom. Toward the end of my last reconnaissance I found a fantastic male specimen at a depth of 79 feet. He appeared as a king seated on his throne with all his pride and an open dorsal fin. As I slowly approached, I realized that he was protruding from a glass jar covered with marine concretions and was most likely taking care of his precious eggs. He was not bothered by my presence, so I took some pictures and left, excited and satisfied to finally have this encounter.

(Nikon D800E, Nikkor 60mm f/2.8 lens, 1/100 sec, f/18, ISO 320, Seacam Seaflash 150 strobe with Retra snoot, Seacam housing; instagram.com/aldo_costa_photography)

Humpback Whale Fluke with Rainbow Spray

Great Bear Rainforest, British Columbia, Canada

By Clemens Vanderwerf

The fjords of the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia are a food-rich hangout spot for humpback whales. Many of them cruise up and down and work in small groups to bubble feed. They create a perfect circle in the water, blow bubbles below a school of fish and shoot up through the middle with their mouths wide open, catching thousands of little fish in one gulp. This humpback whale was cruising along the edge of the fjord, blowing out a spray of water before diving again. The light hit just right and turned the spray into a rainbow against an almost black background.

(Canon EOS-1D X Mark II, EF 200-400mm f/4L IS USM lens at 400mm with 1.4x teleconverter, 1/1600 sec, f/5, ISO 1250; clemensvanderwerf.com)

Nudibranch Trinchesia sp. 62

Tulamben, Bali, Indonesia

By Andrey Shpatak

One of the most beautiful nudibranchs I have ever seen is this Trinchesia sp. 62 while I was diving near Bali. I haven’t seen this nudibranch anywhere else. With a little imagination, we can see a fabulous light in the dark.

(Nikon D800, Nikkor 105mm f/2.8 VR lens, 1/200 sec, f/29, ISO 250, Inon Z-240 strobes (2), Sea and Sea housing; shpatak.livejournal.com)

Japanese Warbonnet

Primorsky Krai, Russia, Sea of Japan

By Andrey Shpatak

The Japanese warbonnet (Chirolophis japonicus), or fringed blenny, is one of the symbolic creatures in the Sea of Japan. Unafraid of divers and very curious, this photogenic fish lives in burrows under stones or in small caves among rocks.

(Nikon D800, Nikkor 60mm f/2.8 macro lens, 1/200 sec, f/9, ISO 100, Inon Z-220 strobes (2), Sea and Sea housing; shpatak.livejournal.com)

Octopus and Spiny Spider Crab

Giannutri Island, Italy

By Filippo Borghi

During a decompression stop at the end of a dive on a cold afternoon in December, I noticed a huge octopus moving strangely behind a rock. As I swam closer, I was surprised to discover a big spiny spider crab trying to escape from a tentacle. Without disturbing the action, I started photographing the pair from a good point of view to give the right impression of the fight. The crab triumphed after cutting the octopus’s tentacle.

(Nikon D800E, Nikkor 10.5mm f/2.8 lens, 1/100 sec, f/16, ISO 200, Ikelite DS160 strobe, Subal housing; instagram.com/filippoborghi5)

Humpback Whale

Vava’u, Kingdom of Tonga

By Jenny Stock

Luck plays its part in wildlife photography, and the Tangaloa (Tongan family of gods) smiled down on me in July as I ventured for some beautiful images of humpback whales. While cruising the waters and watching the horizon for signs, a distant whale announced its presence with a massive flap of its powerful fluke. While snorkeling, I approached the huge, magnificent cetacean and managed to get close enough to see her and her rippled reflection above her. This truly was a moving moment for me, and I rapidly fired off a few shots. I wanted to enjoy the moment longer, but she had other plans. With a wave of her fluke she plummeted to depths I could only imagine.

(Canon EOS 5D Mark II, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L II lens at 35mm, 1/160 sec, f/8, ISO 400, Subal housing; instagram.com/jenniferjostock)

Ocean Glow

Maui, Hawaii

By Peter Lik

Shooting the pure magic of waves is always an unpredictable challenge. Like a surfer, I was glued to the swell report for two weeks waiting for something to happen — waiting for the perfect wave. Sunrise colors were key to this shot, because I wanted that kaleidoscope to reflect through the wave. When a swell was finally predicted for the next day, I packed up my gear and tried to sleep that night. This new experience felt like my first shoot, and I hardly slept a wink. As the sun rose, my expectations were high — I knew the shot would be there. The ocean knocked me around for hours in the surf, but I shot like a madman wave after wave and got this shot.

(Nikon D800, 14mm f/2.8 lens, 1/3200 sec, f/8, ISO 400, Aquatech Elite housing; lik.com)

Mobulas

Cabo San Lucas, Mexico

By Filippo Borghi

Mobulas swim together in an immense aggregation along the coast of Baja, California, from late April until August. During an early morning open-ocean excursion near Cabo San Lucas, I noticed something jumping out of the water not far from our boat. As we slowly got closer, we saw it was mobulas. I immediately jumped into the water to witness this amazing show from under the surface.

(Nikon D800E, Sigma 15mm f/2.8 lens, 1/250 sec, f/8, ISO 200, Subal housing; instagram.com/filippoborghi5)

Jawfish with Eggs

Tingloy Island, Batangas, Philippines

By Mike Bartick

Jawfish are curious animals, poking their heads out from their burrows. This male is carrying eggs that are almost ready to hatch. Its location in shallow water afforded me the time I needed to get as close as possible to accomplish this shot. Adding to the difficulty, this jawfish was facing into the current to help aerate its eggs. In this encounter, however, my luck persisted in nearly perfect conditions.

(Nikon D500, Nikkor 105mm f/2.8 lens with Kraken Pro +6 diopter, 1/200 sec, f/32, ISO 64, Sea and Sea YS-D2J strobe with fiber-optic snoot, Sea and Sea MDX-D500 housing; instagram.com/divecbr)

Tripodfish

Palm Beach, Florida, USA

By Steven Kovacs

I could not believe my luck when I saw this beautiful tripodfish (Bathypterois grallator) drifting along in the blackness. Adult tripodfish are benthic fish that reside in the abyssal zone at a depth from 3,000 feet to more than 15,000 feet. Before settling, the larval fish will drift in the open ocean and rise to the surface at night during the diurnal vertical migration. Blackwater drift dives allow for the observation of such rare and unique animals that would otherwise go unobserved. In Florida, blackwater diving involves going out at night to very deep water, jumping in and drifting in the Gulf Stream near the surface to see what kind of rare and unique pelagic and larval animals you can find.

(Nikon D500, 60mm f/2.8 lens, 1/250 sec, f/20, ISO 200, Ikelite DS160 strobes (2), Bigblue video lights (3), Ikelite housing; instagram.com/steven_kovacs_photography)

Southern Elephant Seal Pup

Carcass Island, Falklands Islands

By Cristobal Serrano

BirdLife International designated Carcass Island, northwest of the Falkland Islands archipelago, as an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA), but some incredible mammals are here as well. This light silvery-fawn southern elephant seal pup likes to explore large areas of kelp. At this stage pups may enter the sea for short forays or gather in small groups some distance from the original breeding sites on their first feeding trip.

(DJI Mavic 2 Pro (Hasselblad L1D-20c), 28mm f/2.8 lens, 1/240 sec, f/2.8, ISO 100; cristobalserrano.com)

Catshark Birth

Argentario Coast, Grosseto, Italy

By Filippo Borghi

Small-spotted catsharks (Scyliorhinus canicula) in the Mediterranean Sea leave their eggs near the end of summer. Having seen five or six eggs during the previous week, I returned to shoot the eggs again, hoping to see some embryos further along in their development. I noticed this egg with the catshark starting to hatch, witnessing for the first time in my life this incredible moment.

(Nikon D800E, 105mm lens, 1/125 sec, f/20, ISO 100, Ikelite DS160 strobe, Subal housing; instagram.com/filippoborghi5)

© Alert Diver — Q3 2019